There is little doubt that the manifold ecological disasters caused by climate change carry the potential to reshape the global political landscape. Some have opted to frame the coming natural disasters, geopolitical upheavals, and migratory waves under a singular heading: climate apartheid. This novel designation garnered some attention in 2019 when UN Special Rapporteur Philip Alston used it in a report outlining a bleak future in which, “the wealthy pay to escape overheating, hunger, and conflict while the rest of the world is left to suffer.”

Despite the ominous prognostications that a “climate apartheid” implies, it is a conceptualization of the climate crisis that remains underdeveloped. In its broadest sense, climate apartheid encompasses the uneven distribution of the climate crisis’ material impacts across discrete populations, whether they be separated by wealth, sovereign borders, or race. Importantly, its manifestation not incidental, but is the logical outcome of the historical processes that produced the climate crisis.

As Alston’s report to the UN suggests, climate apartheid can be understood to anticipate a future order, a reconfiguration of social relations that has yet to materialize. It is also, however, a process presently unfolding, and whose emerging dimensions are inextricably linked to historical projects. To conceive of the ongoing climate crisis as apartheid is to acknowledge how climate change threatens to reproduce the past social and geopolitical relations that laid the foundations for our warming planet in the first place.

As climate disasters increase in scale and frequency across the globe, one notable trend has emerged: the populations experiencing the worst of the climate crisis reside in countries that tend to bear the least responsibility for the onset of the very crisis. In her recent book, Militarized Global Apartheid, Catherine Bestemen notes that while the world’s 48 ‘least developed’ nations collectively account for less than one percent of the carbon emissions responsible for rising temperatures, their residents are five times more likely to die from a climate-related disaster than those in the rest of the world.

The disparate impacts of climate change between the Global North and Global South—despite disproportionate contributions to the crisis—are no historical accident. Studying the postcolonial communities across the Caribbean and southwest Indian Ocean, archaeologists Kristina Douglass and Jago Cooper draw a clear connection between historical imperialist practices and presently unfolding ecological disasters. In the Caribbean, often a site of extreme weather events, “The adoption of European settlement patterns… as well as European household architecture and building materials have increased the relative vulnerability of [postcolonial] communities to hurricane-related flooding and wind shear.” And in Madagascar, decades of deforestation and resource extraction during the colonial period depleted soils, raising the country’s vulnerability to warmer temperatures. This year, Madagascar has experienced its worst drought in four decades, leaving one million people living under the threat of starvation.

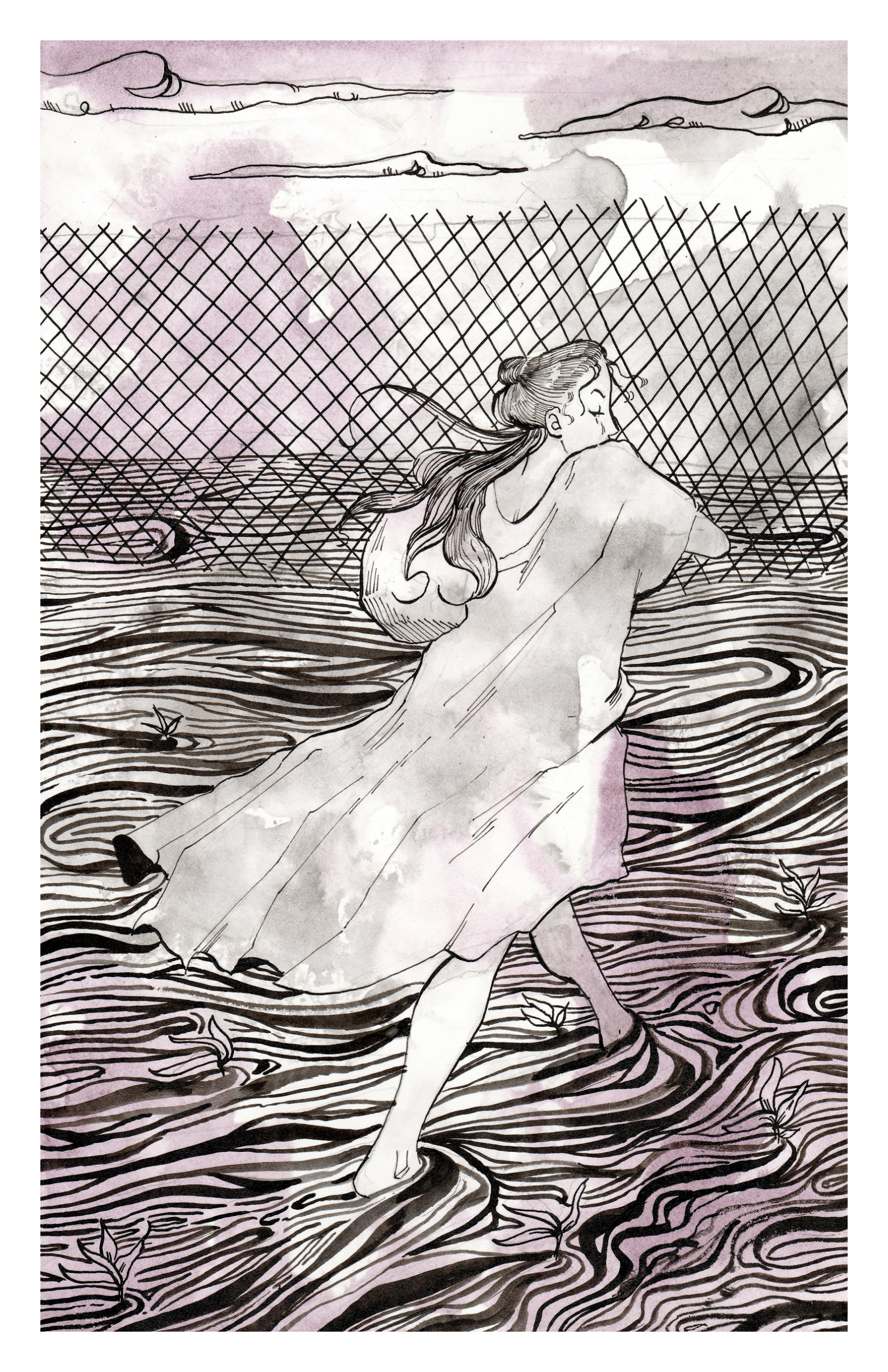

The present manifestations of climate apartheid are hardly limited to these two examples, but their incidence underscores an essential pattern: the relationships of exploitation, subjugation, and separation that characterized our colonial past are at risk of being replicated in the present. Even as climate disasters intensify at an alarming rate in the Global South, the former imperialist states of the Global North, more insulated from the effects of climate change, are fortifying their borders against vulnerable populations facing ever-proliferating possibilities for displacement. For instance, in the wake of the migration surge from the Middle East and North Africa in 2015, the European Union rapidly expanded its border enforcement agency, Frontex, whose budget rose from under 100 million Euros in 2014 to almost 400 million in 2020.

None of this is to say that climate apartheid is limited to imperialist legacies and interstate dynamics. To the contrary, it can equally present itself in patterns of domestic spatial organization, in which race often plays an undeniable role. American philosopher Nancy Tuana identifies such dynamics in the United States’ Southern coal industry. Its growth she writes, was wholly reliant on slave labor in the 19th century and later, after the Civil War, on the labor of the overwhelmingly Black prison population. Not only has burning coal, at times, accounted for almost half of global carbon emissions, but in the United States, communities of color are more likely to be located near an urban coal plant and suffer the debilitating health effects of air pollution. Black children, specifically, are twice as likely to die from an asthma attack than white children.

Climate apartheid identifies the past with present, and it helps reframe how we relate the climate crisis to enduring forms of social inequality. Critiquing the media’s contemporary approach to the climate crisis, journalist Michelle García advocates in The Nation for “intertwined coverage of public health, climate change, racism, and poverty” that accounts for an apartheid reality. Preexisting social inequities invariably determine how the climate crisis unfolds, and any meaningful attempt to address the planet’s changing ecology must acknowledge and confront those historically rooted injustices that define the ongoing climate apartheid.