Last summer, the Justice Department found that Brown had violated Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) by denying readmission to students who had taken leave from the university for mental health reasons. Title III dictates that places of public accommodation — which include schools, restaurants, stores, and more — must grant equal opportunities to students with disabilities. By preventing students who had suffered from mental health conditions from re-enrolling in 2012 to 2017, Brown violated this statute.

The Justice Department’s investigation led to concrete policy changes at Brown, including the institution of mandatory ADA training for all faculty involved in facilitating the leavetaking process. These policy changes were borne in part from the efforts of campus activists. Brown students had been raising concerns about discriminatory leavetaking policies as far back as 2014. Students’ success in helping to catalyze a legal investigation — and eventually holding the University to account for its discriminatory practices — illustrates how fundamental student activism is to ensure disability rights on college campuses. Yet simply lobbying to hold universities to ADA standards is insufficient. In keeping with the demands of disability justice activists, universities must move from a model of bare regulatory compliance with ADA guidelines toward one of what researchers refer to as “full inclusion,” creating campus cultures that go above and beyond providing basic accommodations for disabled students.

While the ADA provides an important framework for disability rights in public spaces like college campuses, its existence alone is insufficient for ensuring that disabled college students receive fully equitable treatment. As the Justice Department’s findings regarding Brown’s leavetaking policies this summer prove, we cannot assume that universities will act in compliance with the ADA without being held accountable by their student body. Sustained student activism is also crucial for holding universities accountable for upholding the principles of equity and inclusion on their campuses, transcending a bare framework of disability rights rooted in compliance with ADA regulations.

Campus activism at Brown, particularly the efforts of Disability Justice, encapsulates the importance of student activism in upholding civil rights at universities. In 2019, efforts by Disability Justice at Brown led to a $50,000 investment from the Office of the Provost in a Disability Study Space at the Rockefeller Library on campus. DJAB aimed to create a space that is “fitted with any and all accommodations disabled students may need,” including “sound-dampening panels on the walls, enclosed chairs, height-adjustable desks, dimmable lighting, and a variety of seating options,” according to its website. DJAB also aims to open a cultural center for students with disabilities on campus, and promotes a variety of other goals, such as the creation of a Disability Studies concentration or program.

Efforts by disability activists have seen similar successes on other college campuses. This past April, amid robust advocacy efforts to bring attention to the substandard quality of Yale’s mental health services from a student group called Mental Health Justice at Yale, the University announced that it was adding 14 full-time staff members to support students’ mental health. The same month, students at Emerson College in Boston launched an Access Advocacy project, which enumerated a comprehensive list of demands to campus administrators to further the goal of disability justice on campus.

These efforts do not only stand to benefit students with known and documented disabilities. A significant hindrance to accessibility in schools is the fact that not all students who have disabilities are able to access the expensive psychometric testing necessary to qualify for certain accommodations. Taking this into account, disability justice advocates on college campuses often promote the notion of universal design, which posits that college campuses and curricula should anticipate and account for the needs of students with disabilities, rather than placing the burden on individuals to seek out accommodations or present proof of their disabilities. Among the demands of Emerson College’s Access Advocacy campaign, for example, are calls to alter absence policies for all students at Emerson, not just disabled students, and to increase the number of take-home assignments.

Expanding these demands to college life in general means removing the onus on disabled students to reiterate their disabilities to professors and campus administrators in order to access crucial resources and accommodations. It also makes the disability justice movement intersectional, recognizing that socioeconomic status can further impede disabled students from receiving the education they deserve.

These recent efforts at ensuring disability justice on college campuses are crucial. If universities like Brown are to fulfill their stated commitments to accessibility and inclusion, they must transcend a bare minimum framework of disability rights set out by the ADA and move toward a more universalized model of disability justice. The voices and efforts of student activists will be crucial in propelling these changes forward, so students on all college campuses, regardless of ability, should lend their support.

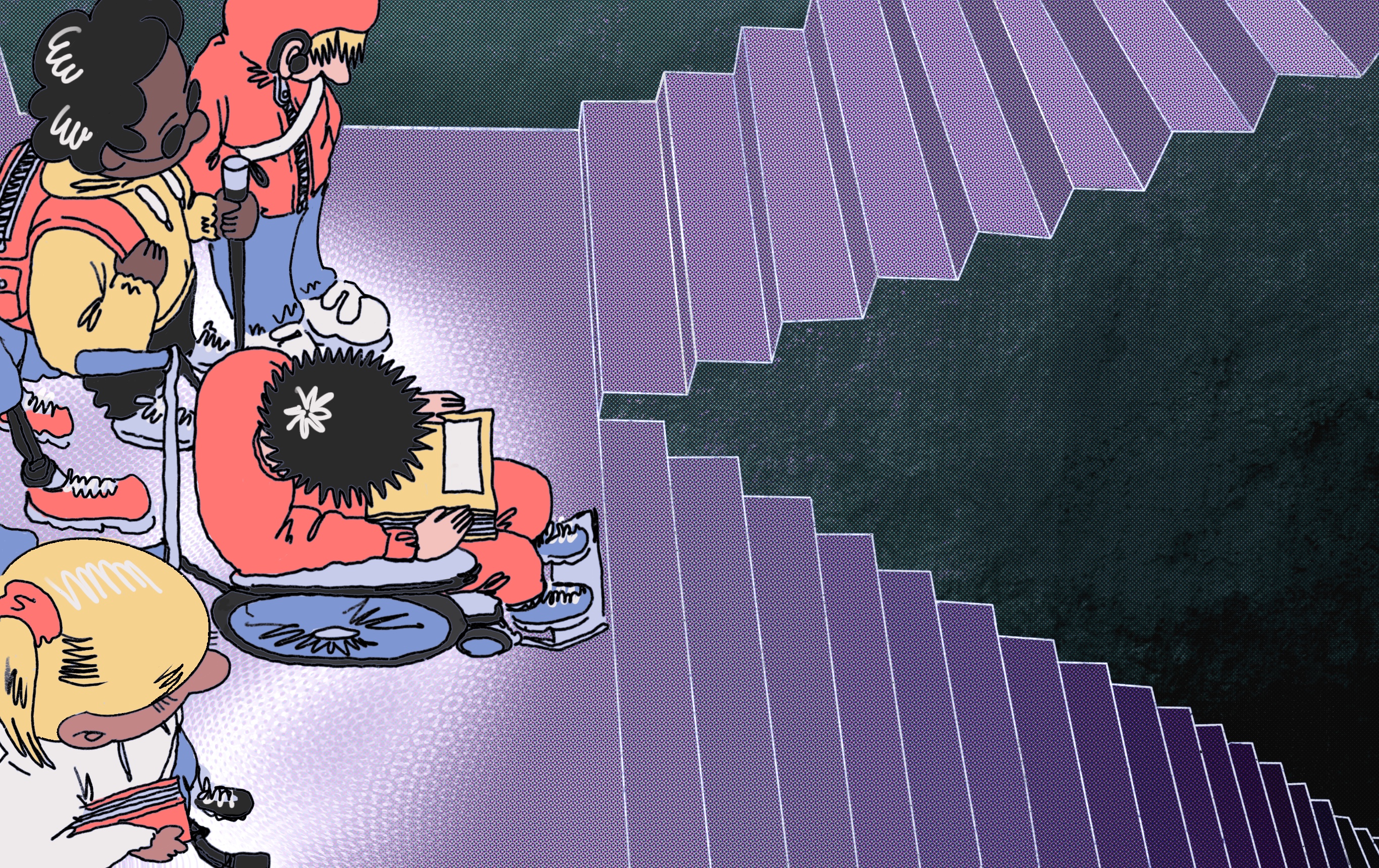

Original illustration by Xuandong Zhou