The name of the influential ’90s Latin American metal band ANIMAL stands for Acosados Nuestros Indios Murieron Al Luchar, which roughly translates to “Harassed, Our Indians Died While Fighting.” That our indios, or Native populations, were mostly exterminated except for a few extant pockets of survival, has become a fixture of contemporary Latin American discourse. In North America, US history books teach students that within 100 years of Columbus’s arrival, the Natives of Puerto Rico had been assimilated, perished from disease, or massacred to the point of nonexistence.

However, the story these books tell is incomplete. Their text perpetrates paper genocide, or the disappearance of entire civilizations in official paper reports, data, and other records. This crime has been committed against several mainland-US Native populations, from the Native American tribes of Virginia, which eugenicist and physician Walter Plecker reclassified as “colored” in Virginia’s 1924 Act to Preserve Racial Integrity, to Rhode Island’s own Narragansett people, who engaged in a centuries-long struggle to achieve federal recognition, which was finally attained in 1983.

Despite this dominant narrative, I grew up hearing from my paternal family that we were, and are, Taínos—the longstanding Indigenous people of the Caribbean with whom Columbus infamously first made contact. My namesake, Guarocuya, comes from a former Taíno cacique, or prince. In the Caribbean, from Borinquen (Puerto Rico) to Xaymaca (Jamaica), there has always been a collective cry seeking to fight the notion that our communities were erased from history. And, although the circumstances of US mainland Native Americans today garners much attention, the parallel experience of Native Americans outside of the 50 states is often forgotten. Terms that include Natives of Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands, such as “Indigenous of the Americas,” have recently come into use.

However, the identity of modern Puerto Ricans differs drastically from mainland Native Americans—it represents a fusion of Taíno, African, and Spanish cultures, with American influence that stems from the territory’s 1898 incorporation. Modern census practices perpetuate the paper genocide of Taínos, feeding into the false settler colonial narrative of our erasure. These practices must be amended to promote interculturalism and allow for self-identification.

The traditional historical discourse maintained by paper genocide is that Puerto Rican Taínos all disappeared through mass suicides and mestizaje (miscegenation), and such mestizaje supplanted any native identity. Terms such as mulatto and mestizo granted Spanish Catholic priests who registered births the power to greatly diminish the official numbers of Taínos. Under US rule, this treatment continued: The US Census limited its race and ethnicity categories to Hispanic, white, Black, or mixed. According to data collected by Spanish authorities, the Taíno population plummeted from an estimated one million at the time of Spanish arrival in 1493 to just 2,300 in 1787. Not one was documented in 1802. To systematically prevent the formation of more federally recognized tribes, the 1802 US Census reclassified any Puerto Rican who identified as “Indian” as “mixed.”

Yet, in the 2020 US Census, over 92,000 Puerto Ricans self-identified as Indigenous. According to a 2016 National Geographic report, the latest genetic research showed that 61 percent of all Puerto Ricans have Native American mitochondrial DNA, revealing “a high number of genetic markers for a supposedly extinct people.” In 2018, a team from the Center for Geogenetics at the University of Copenhagen managed to reconstruct the complete Taíno genome using an 8th to 10th century Taíno skeleton. The researchers were able to establish “clear similarities” between modern Puerto Ricans and Taíno genetic ancestry.

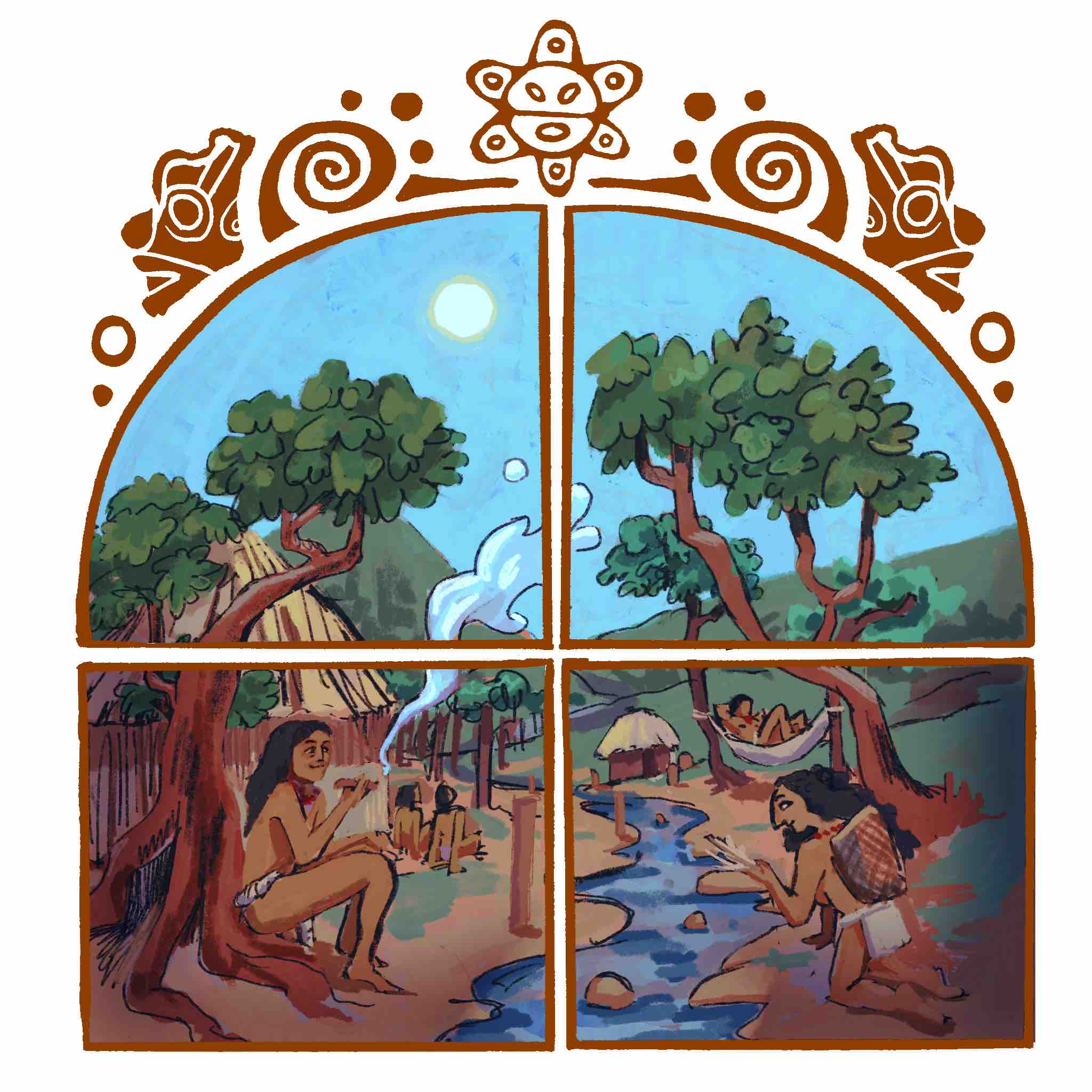

Historians such as Antonio Sotomayor from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign argue that Taíno culture, even more so than African or Spanish culture, had the largest contribution to the formation of a Puerto Rican identity. This is for a very simple reason: It is our mother culture, whereas the other two are overseas cultures. Evidence of Taíno influence abounds, illustrated by the simple example of someone attending a “barbeque” to try some “Caribbean” cuisine, which is infused with a taste of “guava,” going off to smoke “tobacco” while resting in a “hammock” and ending the day by sailing in a “canoe” before the “hurricane” comes. All of these words are of Taíno origin.

The Census Bureau and the Bureau of Indian Affairs’s refusal to acknowledge this evidence perpetuates a paper genocide that has occurred for centuries and clearly indicates the US government’s systematic opposition to Native and Indigenous recognition. At the root of the problem is the issue that in Puerto Rico, a territory that has been under external rule for 528 years, foreign occupiers have always prioritized colonial interests over the diversity of peoples or nations. The Taíno people were—and continue to be—trampled on by a set of legal, political, economic, and social mechanisms that systematically keep Indigenous people out of positions of political power. In the hands of foreign elite, Puerto Rico has institutionalized colonialist systems and policies that maintain the status of the Taíno people as third-class citizens, or even non-citizens.

Oppressive systems have resulted in an American society in which Indigenous peoples are generally the most impoverished populations. Similarly punitive structures have not spared Puerto Ricans. Indigenous people in Puerto Rico suffer from myriad injustices, including, but not limited to, economic depression, poor education, and inadequate healthcare. Colonization has not ended: It may have transformed, disguised, and concealed itself, but it maintains its brutality against the poor.

Unlike colonialism, interculturalism recognizes the reality of a multicultural human family, and it promotes processes that value all cultures in an environment of mutual respect. It seeks to eradicate the historical positioning of dominant and subordinate cultures, instead focusing on appreciating and celebrating human diversity. The goal of interculturalism is the full integration of populations and cultures with their own identities, rather than their assimilation into a dominant national identity. Through intercultural dialogues, the swift judgment of casting out what is different from one’s own culture gives way to considerations of the complexity of human society and diverse forms of human organization.

Along with generally promoting an intercultural perspective, the US Census Bureau and the Department of Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs should allow for self-identification on the basis of parentage, family descent, or genetic ancestry. Proposals to implement self-identification have thus far fallen on deaf ears, largely due to the government’s selfish fear that they would cause many new tribes to spring up and claim reparations or gambling licenses.

In the meantime, modern personal genomics technologies, such as those sold by Ancestry.com, 23andMe, or MyHeritage, allow Taíno descendants to research our ancestry. These genetic tests tell me that I am nearly 8 percent Indigenous American and that my Indigenous composition comes entirely from the Caribbean. This evidence clearly demonstrates the paper genocide committed by federal Native American policies: I carry a Taíno name, speak the Taíno language, and 8 percent of my DNA is entirely Taíno—yet Taínos are extinct? No one dares to deny my African, European, and Jewish roots, yet my Native ones face constant rejection.

Fortunately, hope is not lost: Many modern heritage rescue groups, such as the Taíno Jatibonícu Tribe of Boriken, the Taíno Nation of the Antilles, the United Confederation of the Taíno People, the Guatu Ma-Cu A Boriken Puerto Rico People, and Higuayagua, are actively working to foster and protect the Taíno culture. While many aspects of Taíno culture have been lost over time or mixed with Spanish and African cultures, our heritage remains unique, and we all want to be heard and recognized for who we are.

Works Cited

Anderson, Mark. “When Afro Becomes (like) Indigenous: Garifuna and Afro-Indigenous Politics in Honduras.” Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 12, no. 2 (2007): 384–413. https://doi.org/10.1525/jlat.2007.12.2.384.

Aquino, Luis Hernandez. “Diccionario De Voces Indgenas De Puerto Rico.” Google Books. Editorial Cultural, 1977. https://books.google.com/books/about/Diccionario_de_voces_ind%C3%ADgenas_de_Puert.html?id=OpkuAAAAYAAJ.

Brockell, Gillian. “Here Are the Indigenous People Christopher Columbus and His Men Could Not Annihilate.” The Washington Post. WP Company, October 14, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/10/14/here-are-indigenous-people-christopher-columbus-his-men-could-not-annihilate/.

Estevez, Jorge, Rene Perez, and Keisha Josephs. “Origins of the Word Taino.” ResearchGate, September 2016. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/296694496_Origins_of_the_word_Taino.

Magazine, Smithsonian. “Ancient DNA Contradicts Historical Narrative of ‘Extinct’ Caribbean Taíno Population.” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, February 22, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/ancient-dna-contradicts-historical-narrative-extinct-caribbean-taino-population-180968221/.

Marcus, Susan. “Virginia’s Racism toward Its First People Cannot Be Forgotten.” The Washington Post. WP Company, December 12, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/virginias-racism-toward-its-first-people-cannot-be-forgotten/2019/12/12/189ae1f4-1b6a-11ea-977a-15a6710ed6da_story.html.

Martinez-Cruzado, Juan C. “The Use of Mitochondrial DNA to Discover Pre-Columbian Migrations to the Caribbean: Results for Puerto Rico and Expectations for the Dominican Republic.” ResearchGate, 2002. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26406975_The_Use_of_Mitochondrial_DNA_to_Discover_Pre-Columbian_Migrations_to_the_Caribbean_Results_for_Puerto_Rico_and_Expectations_for_the_Dominican_Republic.

Miller, Greg. “How Mapmakers Help Indigenous People Defend Their Lands.” Culture. National Geographic, May 4, 2021. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/indigenous-cultures-mapping-projects-reclaim-lands-columbus.

Montgomery, Michelle R. “Identity Politics of Difference: The Mixed-Race American Indian Experience.” Tribal College Journal of American Indian Higher Education, March 14, 2019. https://tribalcollegejournal.org/identity-politics-of-difference-the-mixed-race-american-indian-experience/.

Muratorio, Blanca. “Indigenous Women’s Identities and the Politics of Cultural Reproduction in the Ecuadorian Amazon.” American Anthropologist 100, no. 2 (1998): 409–20. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1998.100.2.409.

Nations, United. “United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples for Indigenous Peoples.” United Nations, 2007. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html.

Schroeder, Hannes, Martin Sikora, Shyam Gopalakrishnan, Lara M. Cassidy, Pierpaolo Maisano Delser, Marcela Sandoval Velasco, Joshua G. Schraiber, et al. “Origins and Genetic Legacies of the Caribbean Taino.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, no. 10 (2018): 2341–46. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1716839115.

Sotomayor, Antonio. “La Colonia Soberana: Deportes Olímpicos, Identidad Nacional y Política Internacional En Puerto Rico.” CLACSO, January 1, 2020. https://www.academia.edu/43426665/La_colonia_soberana_Deportes_ol%C3%ADmpicos_identidad_nacional_y_pol%C3%ADtica_internacional_en_Puerto_Rico.

Via, Marc, Christopher R. Gignoux, Lindsey A. Roth, Laura Fejerman, Joshua Galanter, Shweta Choudhry, Gladys Toro-Labrador, et al. “History Shaped the Geographic Distribution of Genomic Admixture on the Island of Puerto Rico.” PLoS ONE 6, no. 1 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016513.

Wade, Lizzie. “Genes of ‘Extinct’ Caribbean Islanders Found in Living People.” Science, 2018. https://www.science.org/content/article/genes-extinct-caribbean-islanders-found-living-people.

Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240.

Yong, Ed. “How Ancient DNA Can Help Recast Colonial History.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, September 18, 2019. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2019/09/what-ancient-dna-says-about-puerto-ricos-history/598246/.

The problem with your solution for the Puerto Rican’s for the DOI to grant them Indigenous Status with Genomics is ridiculous because the Native Americans are more than just some vague racial category, when they are not a race but sovereign Nations all the way back into history who signed treaties ceded land and signing treaties that are the law of the land. If the government started using dna and indigenous blood, then Mexicans and all of Latin America from Mexico to Chile would be considered indigenous since these people who have indigenous dna 3-4 times the Amount to Puerto Rican’s who’s major genetic and cultural influences are African and European ancestors forum