Many liberals cheered the deportation of Novak Djokovic, then the top-ranked male tennis player in the world, from Australia the day before the calendar year’s first Grand Slam tournament in Melbourne. They saw in Djokovic an irresponsible figure—one who had hosted a charity-turned-superspreader event early in the coronavirus pandemic, voiced controversial opinions on holistic medicine tantamount to quackery, neglected to quarantine immediately after being infected with Covid-19, and, of course, refused to get vaccinated against the virus—and in his expulsion another prudent public health measure taken by Australia. Indeed, the Washington Post’s Kate Cohen proclaimed a “victory for … the Rule Followers” as both Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Health Minister Greg Hunt emphasized Djokovic’s failure to comply with border policy requiring proof of vaccination or a valid medical exemption. In Morrison’s definitive words, “that’s what this is about.”

Even a cursory glance at Immigration Minister Alex Hawke’s official statement pronouncing Djokovic’s removal, however, reveals the decision had nothing to do with the tennis star’s supposed noncompliance with entry regulations nor any concrete health risk he posed. Rather, Hawke wielded his unilateral powers under section 133C(3) of Australia’s Migration Act 1958 to banish Djokovic on “health and good order grounds, on the basis that it was in the public interest to do so,” given Hawke’s subjective calculation that Djokovic’s presence in the country would stir up anti-vaccination sentiment. Then, a three-judge panel upheld Hawke’s judgment not on the merits of his claim but merely because Hawke was within his rights to dismiss Djokovic arbitrarily. Accordingly, liberals should beware of celebrating the Australian government’s handling of the so-called “Djokovic Affair,” for the saga is less about the man himself and the vaccine he refused to take than it is extraordinary executive overreach on matters of immigration. Further, the verdict points to Australia’s long tradition of restrictive, if not hostile, immigration practices that persist to the modern day.

Supporting the outcome of Djokovic’s case unduly legitimizes an Australian government that has a decades-long history of implementing severe and discriminatory immigration programs. For most of the 20th century, the country operated under a “White Australia” policy that effectively barred all non-Europeans by giving entrance exams exclusively in European languages and also aimed to deport “undesirable” migrants already in the country. The specter of military invasion by Japan after its victory in the Sino-Japanese War and the influx of cheap labor from Asia, combined with racist attitudes towards nonwhites, brought the act into existence and led to the creation of an overwhelmingly white, insular society. Nevertheless, with waning migration from Britain and the need to “populate or perish” growing more urgent, Australia began admitting a wider range of immigrants post-WWII. New laws introduced in 1966 replaced the race- and nationality-based admission process with one based on skills and “ability to contribute to Australian society.” The 1973 Labor administration headed by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam officially renounced the White Australia policy and in its stead codified the concept of a multicultural Australian society ostensibly free from racial discrimination.

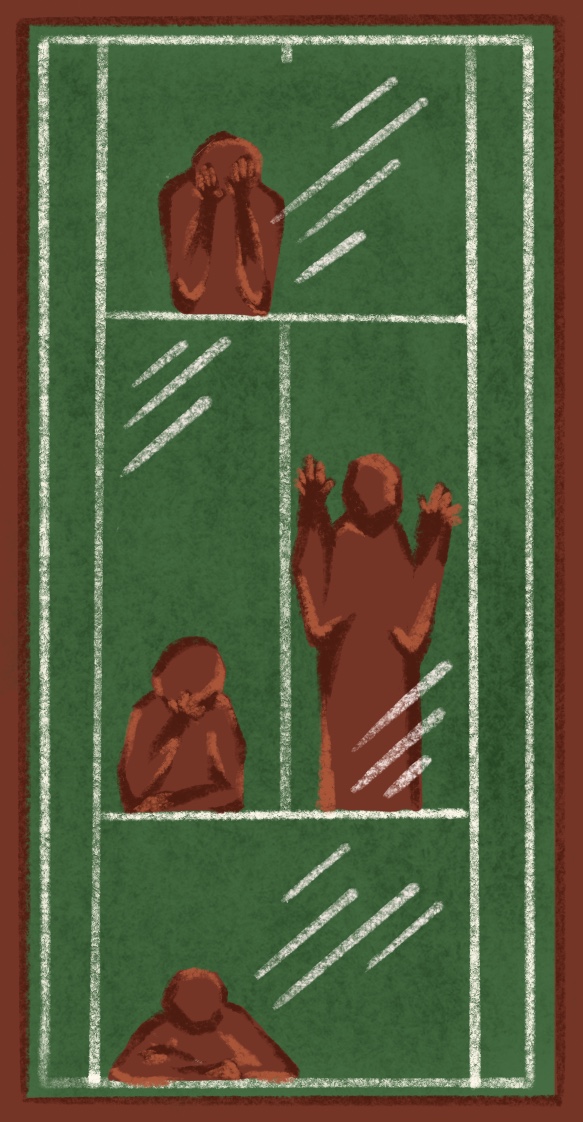

Despite progress toward openness and inclusivity, the Australian government continues to subject migrants to cruel and unfair protocols. The Park Hotel in Melbourne, where Djokovic was kept in custody while he appealed the initial cancellation of his visa, stands as a prime example of Australia’s sustained draconian posture on immigration. Since December 2020, the Australian Border Force has converted the hotel into a holding pen for some 30 refugees and asylum seekers who arrived at ports of entry by boat. Upon arrival, these migrants got thrown into offshore detention facilities on neighboring Papua New Guinea and Nauru along with thousands of others under a 2013 military-led border security policy dubbed “Operation Sovereign Borders” that aimed to deter maritime migration with a zero-tolerance approach. After enduring years of inhumane conditions in camps that lacked proper electricity, food, water, and medications, and where residents faced constant threats of violence, this cohort was brought to the mainland for medical treatment. The Park Hotel, though, has offered little reprieve from suffering, as its inhabitants report being deprived of fresh air and fed insufficient meals. They are forced to gaze out at normal life while they languish in indefinite confinement. Human rights advocates sought to capitalize on the media attention awarded to Djokovic by protesting the refugees’ mistreatment outside the hotel, but it is unclear whether the outcry will lead to substantive change considering the government’s intransigence and largely tepid public opinion.

Moreover, structural issues allow for undue executive authority over immigration resolutions, insulate elected officials from accountability, and ultimately perpetuate the Australian government’s harmful procedures to the detriment of migrants. The Migration Act grants the immigration minister a sweeping mandate to deport individuals on character or public interest grounds, as when Hawke booted Djokovic for purportedly being a “talisman of anti-vaccination sentiment” who would provoke “civil unrest.” Amendments to the Act in 2014 also fueled a tide of mass visa cancellation for thousands convicted of criminal offenses and granted the government “clear removal powers” for these individuals. Additionally, immigration policies crafted via executive order are not required to be published in the Australian federal register like in the United States, enabling officials to act without public or judicial scrutiny. Such was the case with former Minister for Immigration Scott Morrison’s “turn-back” command for vessels harboring asylum seekers as part of Operation Sovereign Borders. After a three-year Freedom of Information struggle, the directive was published but only in redacted form. Finally, since Australia lacks a bill of rights guaranteeing basic constitutional protections like a speedy trial, asylum seekers detained offshore or at the Park Hotel can be held there as long as the government chooses.

When the pandemic hit, Australia enacted one of the harshest set of restrictions on international travel in the world. While the government’s actions helped keep Covid-19 infection and death rates comparatively low, the steps appeared to have been fueled by and at once reinforce Australia’s isolationist tendencies. A majority of the Australian populace supported resuming migration at a lower level than before the coronavirus, suggesting that cynicism about foreigners only deepened.

Viewed in the context of Australia’s historic and current immigration policies, Djokovic’s deportation seems in retrospect to have been the inevitable product of the system in which he became ensnarled. Make no mistake, though: It was far from a principled stance by a country committed to standing up to anti-vaxxers in the name of public health, and liberals should not laud it as such. The Australian government—specifically, its immigration minister—flexed its might like it has on so many occasions over scores of (less-privileged) border crossers. Only this time, it could make a high-profile example out of one of them.