When Queen Elizabeth II died on September 8, 2022, the world seemed to come to a brief but crashing halt. While many leaders from across the world offered their condolences and tributes, another issue was spotlighted—the monarchy’s role and complacency in the colonial and racist history of the British Empire. An especially interesting conversation began to unfold in the 14 Commonwealth Realm nations that still claim the British monarch as their head of state and the 54 member states of the Commonwealth of Nations. National discussions are sparking in places like Jamaica on whether to remain or not as a Commonwealth Realm nation. In fact, the Prime Minister of the Bahamas—right after signing the Queen’s book of condolences—declared his intentions to hold a referendum on turning his nation into a republic. While some may dismiss the influence of the Commonwealth, it has become increasingly clear that the legacy of the British Empire continuously impacts its former colonies, which cannot be forgotten.

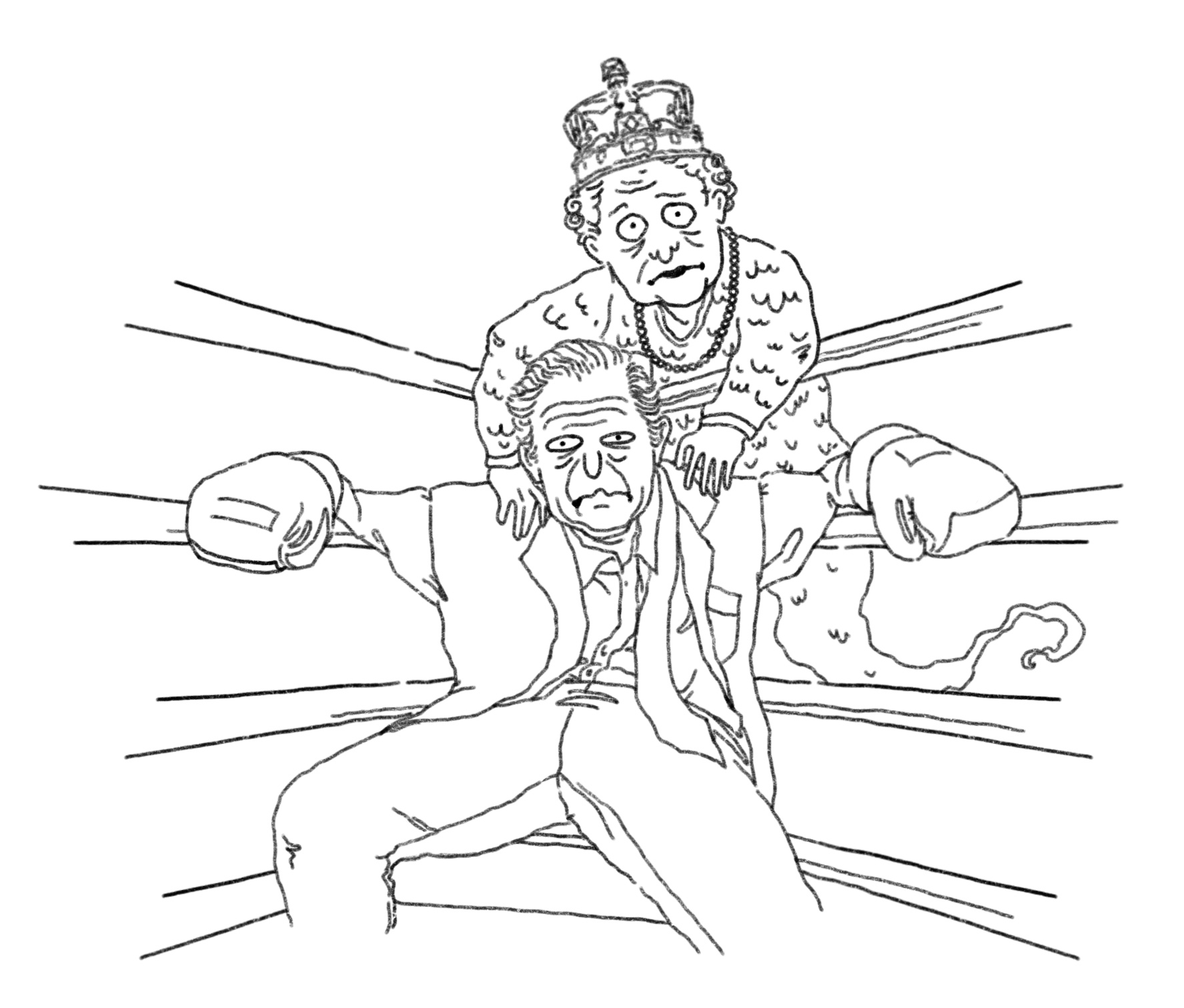

The negative attitudes toward the British monarchy precipitated Queen Elizabeth’s death, spurring nations like Barbados to seek complete separation from the monarchy. In 2021, Barbados became a Republic and abolished their monarchy. A year later, the British prince and princess, Willliam and Kate, toured the Caribbean, a trip that many theorize was planned to respond to Barbados’ separation. Yet, a day after William and Kate’s visit to Jamaica, the island’s government began proceedings to become a republic.

While analysts expect Jamaica’s path to becoming a republic to be possible, rough constitutional and political ramifications are likely. Jamaica will have to comprehensively review its original 1962 constitution, analyzing not just issues relating to the head of state, but also charters relating to fundamental rights and freedoms. The nation has already created a new Ministry for Legal and Constitutional Affairs to take on these difficult tasks. The country will also have to hold a referendum, scheduled for 2025, with a positive vote of at least a two-thirds majority—another hurdle baked into the country’s original constitution. Legal experts have cautioned that potential changes to the Jamaican constitution could include hidden less-popular changes, as well as risk that political opponents attempt to use the changes to further their own agendas. Some, like Barbadian political analyst Peter Wickam, have gone as far as to say that “[he doesn’t] believe that [Jamaican separation] will ever happen because the referendum will be manipulated by political parties.”

Jamaica would not be the first nation to unsuccessfully attempt a major constitutional change. Failed referendums include Australia in 1999, the Bahamas in 2002 and 2016, St. Vincent and the Grenadines in 2009, Grenada in 2016 and 2018, and Antigua and Barbuda in 2018. While each situation was different, all the referendums share the same problem: containing the fear of massive constitutional overhaul and political exploitation by rival parties.

Up north, another Commonwealth Realm faces similar issues. In Canada, where polling in 2022 shows that 51 percent of Canadians do not want to continue with the monarchy and 77 percent feel no attachment, demonstrates that mounting any serious attempt at a republic would require extraordinary circumstances. An attempt at removing the Crown in Canada would require the approval of several legislatures and a massive constitutional overhaul. Additionally, most treaties with Indigenous people in the country were signed with the British Crown and not the Canadian government. As Canadian political scientist Jonathan Malloy puts it, “Canada went down this road in the 1980s and 1990s and the country nearly collapsed from all the competing demands.”

As such, there are incredible challenges that Commonwealth Realms would have to face to leave the British monarchy. Barbados took 40 years of debate and work to establish their republic—the first since Mauritius separated from the Commonwealth in 1992. While this restriction is not mainly the result of current actions by the British monarchy, the legislation and structures of governance directly attributed to the British Empire still have deep ramifications for the former colonies.

To deal with all of this mess, why would a country want to go through all the trouble of leaving? Does the reasoning for nations wanting to leave the Commonwealth stem from more than simple optics and symbolism? The answer is a resounding yes.

In fact, Britain continues to have a judicial and diplomatic hold over many Commonwealth nations. The highest legal court of appeal for eight independent countries within the Commonwealth is still the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council based in London. This legal control has notably manifested in longstanding disagreements between the Privy Council and some Caribbean nations on forgoing the death penalty in which decisions were unilaterally made by the council without input from a region with relatively high support for capital punishment.

Britain also exerts significant influence over its former colonies through diplomacy. One of the most important roles of the British monarchy is to serve as a diplomat and preserve partnerships with constituent nations. Therefore, the Commonwealth has a public attachment to Britain and their diplomatic policies. After all, Commonwealth Realm nations still need the monarch’s approval to sign off on ambassadors and diplomats. As political scientist Joseph S. Nye observes, “the Queen and the Royal Family have been pivotal in maintaining [Britain]’s relevance.” This diplomatic relationship between Britain and Barbados was a strong consideration in Barbados’s decision to become a republic and continues to be an active discussion for Commonwealth Realms today. The role of the monarchy is not to be underestimated.

When the Queen passed, it marked more than the death in a ceremonial institution. Despite assertions by some that the British monarchy remains purely symbolic, nations and Commonwealth citizens need to understand the nuanced role that Britain still plays in their countries to this day. These countries need to stay careful in their own quests to define their own identities, lest they blindly run into the hurdles faced by Australia, Canada, and several more nations before them. Regardless, the path of republicanism is not one to be disregarded. Commonwealth realms must fully contemplate what their relationship with the Commonwealth means for them—both symbolically and strategically. In regards to her nation’s own new republic, Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley aptly stated that her nation’s laws finally would not be “signed off on by those who are not born of here, who do not live here, and who do not appreciate the daily realities of those who live here.”