In 1995, Bai Junfeng tortured and then forcibly penetrated his wife Yao, leading her into a coma that nearly took her life. Yet the Yixian People’s Court ruled that Bai was innocent of rape on the grounds that violently forcing one’s wife to have sex is not rape according to Chinese law. The Court argued that the marriage contract constitutes a permanent and irrevocable consent to sexual relations, so husbands are legally justified in forcing sex upon their wives.

Such a verdict was only possible because China lacks any laws prohibiting marital rape; neither its first piece of domestic violence legislation passed in 2015 nor its pre-existing rape laws address non-consensual sexual relations between spouses. This massive omission contributes to continuing violations of women’s rights and human dignity. The government must address this crisis by recognizing marital sexual violence as a crime. Doing so would represent a significant step forward for human rights in China.

The marital rape exemption has allowed sexual violence within marriage to remain both pernicious and prevalent for decades. In fact, a 2013 study led by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) found that 10 percent of Chinese women surveyed who had ever been in an intimate relationship reported experiencing rape at the hands of a male partner. Similarly, 14 percent of men who had ever had an intimate partner admitted to forcing penetrative sex upon their female partners, while 22 percent admitted to coercing their partners into any sexual act. This reported abuse was not just widespread but also relatively frequent; 9 percent of men reported sexually assaulting their intimate partners within 12 months of when they were surveyed.

Unsurprisingly, intimate partner violence (IPV) like that reported by the United Nations Population Fund is extremely damaging to survivors, both physically and psychologically. A United Nations report found that Chinese women who have experienced IPV were “two to three times more likely to have poor overall health, be unsatisfied with their sexual life, have contracted sexually transmitted infections, had miscarriages and/or abortions, be clinically depressed and consider or attempt suicide” than women who have not. Evidence also suggests that the psychological consequences of IPV are more profound for survivors of marital rape who, in addition to experiencing the violation of autonomy that all rape survivors are subjected to, also undergo violations of trust by individuals close to them.

The Chinese government’s refusal to categorize these violations as crimes reflects its long-held prioritization of protecting the chastity, or zhen cao, of women over protecting women themselves. Historically, rape laws in China have been written with the goal of protecting the husband’s property. Because this property right extended to the ownership of a wife’s sexual purity, female chastity was of the utmost importance. With traditional Chinese attitudes largely considering men as superior to women, it’s no surprise that rape laws prioritize men’s property rights over women’s sexual freedom and physical and emotional wellbeing.

These attitudes largely stem from long-standing Confucian beliefs in the importance of natural hierarchies in preserving social harmony. One of the most prominent of these hierarchies is the division between the sexes: Women, associated with the Yin symbol, are expected to be subservient to men, who are considered superior as a result of their identification with the Yang sign. Consequently, wives are expected to demonstrate unwavering obedience to their male heads of household. Historically, a wife’s sexual loyalty to her husband has represented the pinnacle of this obedience and has even been compared to the political loyalty demanded of citizens to their state.

This view of appropriate sex as tied to filial piety (xiao) is revealed in the legal codes of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, which defined illegal sex (jian) as “vaginal intercourse outside marriage.” This language implies that sex within marriage is intrinsically legitimate, and that marital rape is an oxymoron. By these dynasties’ laws, outside of a marriage, there is a distinction between consensual and non-consensual sex. Within a marriage, no distinction exists.

When these definitions of sexual assault pervaded rape laws, the consequences for women were profound. The Ming-Qing-era prevalence of cases of “marriage by abduction” serves as one extreme example of such a consequence. In marriage by abduction cases, grooms who feared their brides’ families might delay or break off their engagement kidnapped and raped their future brides in order to secure their marriage contract. Since marriage constituted a covenant between male heads of household, the only relevant legal question when these cases were brought to court was whether the marriage negotiations were legally acceptable. If they were not, then the groom would be guilty of coercive illicit sex since it took place outside marriage. If the marriage contract was valid, however, then it was deemed that there was no foul play, and the violence the wife experienced was legally irrelevant.

This is because Chinese law did not recognize the rights of women—or anyone else for that matter—until the 20th century. Rather, as historian Matthew Sommer explains, “it would be more appropriate to speak of the ‘duties’ and ‘privileges’ that are attached to different roles within the kinship hierarchy” than the rights a modern legal system might acknowledge.

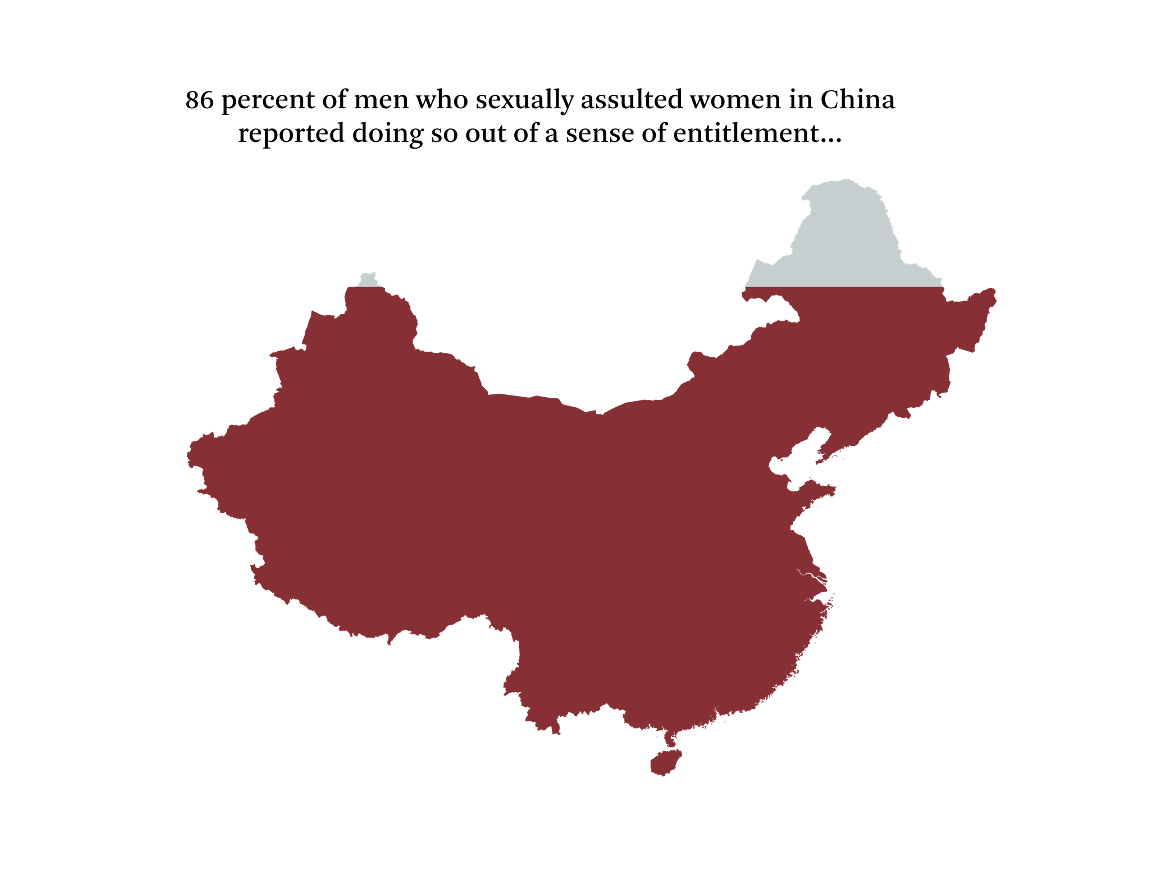

The view of sex from this perspective is still prominent in modern times. In the 2013 UNFPA study, 41 percent of men and 33 percent of women surveyed in China believed that “a woman cannot refuse to have sex with her husband.” Furthermore, almost 24 percent of men and 26 percent of women surveyed agreed that “if a man has paid bride price for his wife, he owns her.” These polls reveal the enduring power of patriarchal beliefs, in part tied to Confucianism, that men are justified in dominating their wives, especially with regard to sex. These beliefs not only justify marital rape in theory but also encourage it in practice: 86 percent of men who have raped women cited their conviction that they had the “right to have sex even by force” as a motive.

These misogynistic attitudes, combined with the cultural value placed upon family unity, hinder wives from reporting or even sharing their experiences of abuse. The Confucian emphasis placed upon household harmony means that family discord is considered catastrophic since it disrupts societal order. In order to avoid disunity, all members of the family, particularly women, are expected to make individual sacrifices for the benefit of the collective. For wives of abusive husbands, this can mean choosing not to report violence or pursue an official protective order against their abuser for the sake of their families.

Even in the rare instances in which women do come forward, their voices are often silenced by law enforcement officers who uphold the idea that intimate partner violence belongs in the private realm. For example, after 23-year-old Ah Lian was beaten and raped by her husband, she was told by police officers to “just work it out” with him. Disturbingly, her experience is not uncommon: Police and judges regularly brush off claims of spousal violence, encouraging women to return to their husbands to preserve their marriages and families. As a result, protection orders are infrequently granted or enforced.

The prevalence and persistence of cultural attitudes rationalizing violence against women and silencing their stories clearly demonstrate that legal changes will not be a panacea for rape and sexual assault within marriage. Rather, addressing this epidemic will require widespread, long-term cultural changes that move China away from its patriarchal roots towards a more egalitarian future. Still, legal recognition of marital sexual violence as a crime is nonetheless a necessary first step towards achieving this future; Chinese women are more likely to experience rape by intimate partners than other perpetrators, so sexual violence legislation should reflect this reality. Criminalization would provide a legal basis that would enable women to seek safety from abusive partners. At the same time, it would send a social signal that women do not renounce their rights to autonomy, respect, and human dignity when they enter marriage.