“How do we sum up the expectations that the peoples of Africa had on the eve of independence, or evaluate what has happened to those hopes and aspirations since the coming of political independence?” In this quote, the late Nigerian historian Jacob Festus Ajayi contemplates the state of affairs in postcolonial Africa. In the eyes of Ajayi, the promise of prosperity that once echoed throughout the continent did not materialize. Specifically, promises of economic prosperity by means of socialist economic reform were not kept. As such, in this article, the case study of Tanganyika, renamed Tanzania after independence, will be used to examine the ravaging socialist economic sentiment on the continent and its subsequent failure.

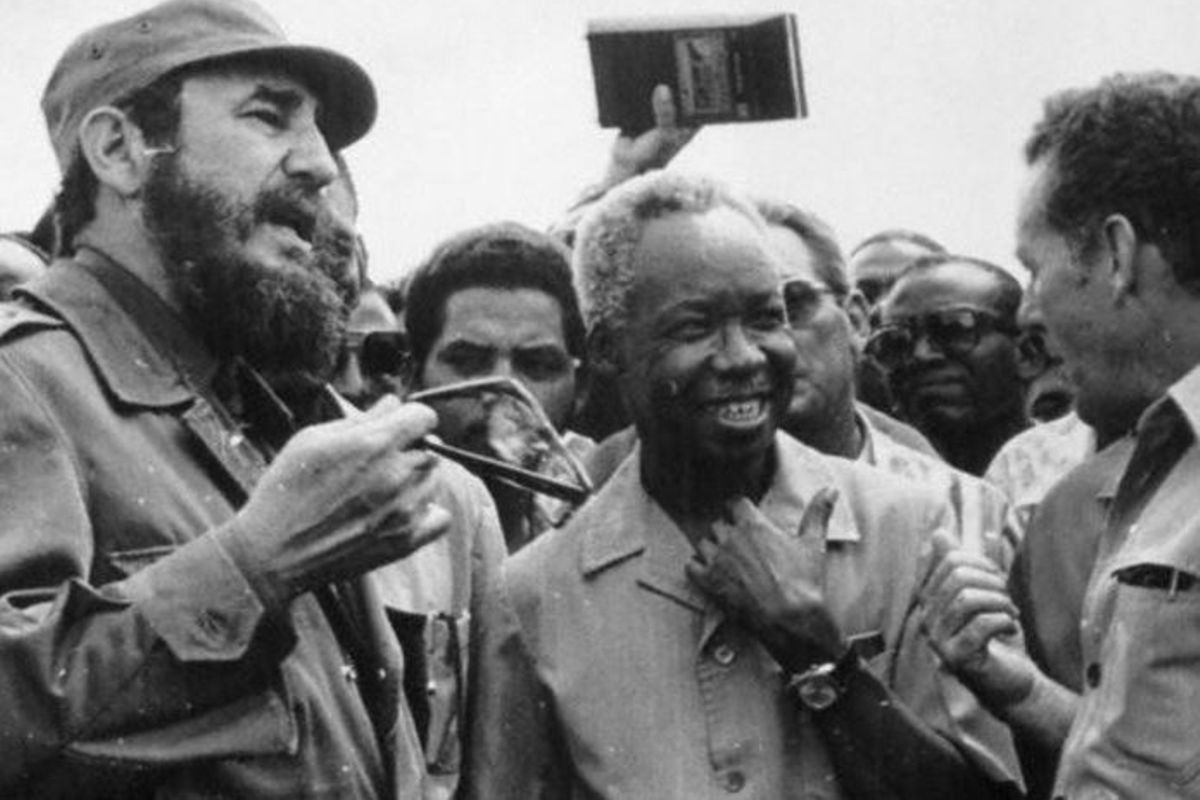

In 1948, a nationalist movement erupted in the British colony of Tanganyika with the creation of the Tanganyika African Association (TAA) by anticolonial activists in the colony. In the ranks of the association was Julius Nyerere, the future nationalist leader of Tanganyika. Whilst Nyerere is not the focus of the article, it is interesting to consider this individual’s background to illustrate Tanzanian economic socialism in post-independence Africa.

In pursuit of an education, Julius Nyerere attended the University of Edinburgh. While in Scotland, Nyerere became involved in the Fabian Society, an organization that advocated for a socialist, anticolonial agenda. His participation in the Society motivated the future nationalist leader to raise the political consciousness in Tanganyika. Upon his return to Tanganyika from Scotland in 1954, Julius Nyerere renamed the Tangayikan African Association the Tanganyikan African National Union (TANU). To little surprise, the newfound political party embraced an ideology of equality, anticolonialism, and socialism. In Tanzanian society, this ideology became known as Uhuru na Ujamaa—Freedom and Socialism. The party platform went on to shape the economic policies of prosperity implemented in post-independence Tanganyika (newly dubbed Tanzania). As Christensen and Laitin discuss in their book, From Great Expectations to Unfulfilled Dreams, President Nyerere enacted socialist economic policies that nationalized banks, sisal estates, and other large establishments.

However, as Jacob Ajayi argues in “Expectations of Independence,” while African nationalist leaders sought to spread socialist policies to construct postcolonial nations, these efforts were typically unsuccessful. And, the East African nation of Tanzania was no exception.

A decade after the former British colony of Tanganyika was granted independence, the country was met with internal resistance to its socialist policy of Ujamaa, eventually leading to its failure. The domestic opposition to Ujamaa stemmed from local, ethnically South Asian communities in Dar es Salaam, which consisted of orthodox capitalists and the commercial class, and the bureaucratic community, which included wealthy farmers, industrialists, and employees of foreign-owned companies. From the perspective of these two groups, the Ujamaa policy was squandering the nation’s resources on the idealistic notion of egalitarian solidarity. As the late 1970s and early 1980s saw the serious disaster of “Tanzania’s dysfunctional socialist economy,” the two resistance communities grew more distrustful of the Ujamaa policy and sought to frustrate its development even further. Both groups engaged in negotiations with foreign investors and Western aid agencies. These negotiations undermined the Ujamaa policy, as the presence of capitalist investors in Tanzania hindered its execution. Overwhelmingly, those “responsible for implementing” the policy “only focused on their interests.” As put by journalist Leander Schneider, “Economic shocks [pushed Ujamaa] off the cliff.”

Ultimately, at a 1992 special congress in Dar es Salaam, President Julius Nyerere stated that, “Changes have become imperative, and inevitably we must admit our previous mistakes and build afresh.” These words by the former nationalist leader marked the end of three decades of notorious African socialism in Tanzania. Thereafter, the world witnessed the unmaking of Tanzanian economic policy and its parade toward capitalism—more specifically, “Africapitalism.” A term created by Nigerian businessman Tony Elumelu, Africapitalism is “an economic philosophy that embodies the private sector’s commitment to transform Africa’s economy through long-term investments that generate both long-lasting economic prosperity and social wealth for all Africans.” In recent years, it has dominated the Tanzanian economic sphere through the commercial agricultural business. For example, Mtanga Foods in Tanzania “[serves the full value chain of its operation, focusing on production, processing, distribution, and retailing].” It has supplied over 150,000 farmers, and as a result, transferred sustainable technologies to the Tanzanian Ministry of Agriculture. This give-and-take relationship between the private and public sectors in Africa lies at the heart of Africapitalism. It opens the public sector to new entrants, and thus creates jobs for local African populations. Evidence of the positive economic impact of this policy is the 64 percent increase in Tanzania’s real GDP per capita between 1990 and 2008, which translates to an impressive 2.8 percent increase per year. Africapitalism is being developed in Africa, “born out of the African historical experience and the sense of continuity of the African [legacy].” That is its significance.

From its inception in the 1960s, socialism in Tanzania was the crown jewel of socialist economic thought on the continent. Ujamaa was perfect in theory — the policy was built on an agrarian model of collectivized villages and small-scale farming that uplifted the spirit of citizen cooperation. But Tanzanians were divided under Ujamaa; it was not a policy for or by Africa. Conversely, the new landscape of Africapitalism calls for unity and involvement to rise from within the African continent.

With that, Africapitalism represents a novel opportunity to elevate Africa from the economic shadows. As put by Elumelu, “Africa is capitalism’s final frontier.” For Africapitalism to succeed and not experience the same fate as socialism on the continent, a new story must be written in the unbearable heat of Dar es Salaam, separate from the chills of the Western bloc.