Debates about fertility rates rage around the world. India is no exception. As a country where family and children are valued above nearly all else, this fact is unsurprising. But focus on family often comes at great cost for India’s women. In a nation where screening for gender during pregnancy was outlawed due to sex-selective abortions and female infanticide, the cultural value of having a son is immense. Sons are favored in childhood, and many women end up in abusive marriages with their lives controlled by both their husbands and in-laws. These issues have long been pushed to the backburner in favor of supposedly more pressing matters such as excessively high birth rates. But although it recently surpassed China as the world’s largest country, India’s fertility rate is slowly declining below replacement level, providing an opportunity for its society to reckon with its next big challenge: gender inequality.

Family planning began shakily in India. Under the guidance of the UN Population Fund, India began an ambitious family planning campaign in the 1970s aimed at lowering the birth rate from a jaw-dropping six children per woman—a phenomenon known as “The Population Bomb,” stemming from the book by Paul Ehrlich. It did so through a horrific campaign that in just one year resulted in the forced sterilization of over 6.2 million men, many of them low-income. However, family planning efforts have since largely focused on women, as they are seen as easier to control.

Over the last 50 years, family planning in India has grown, largely through women voluntarily using birth control and choosing to have fewer children. Today, the average Indian family has just 2.1 children, meaning the country is at replacement rate for the first time in its history—a fact that was celebrated as a triumph of government control. The trend of decreasing growth in fertility rates is likely to continue as more Indian women go to school, given that improving education rates among women is one of the greatest drivers of more effective family planning.

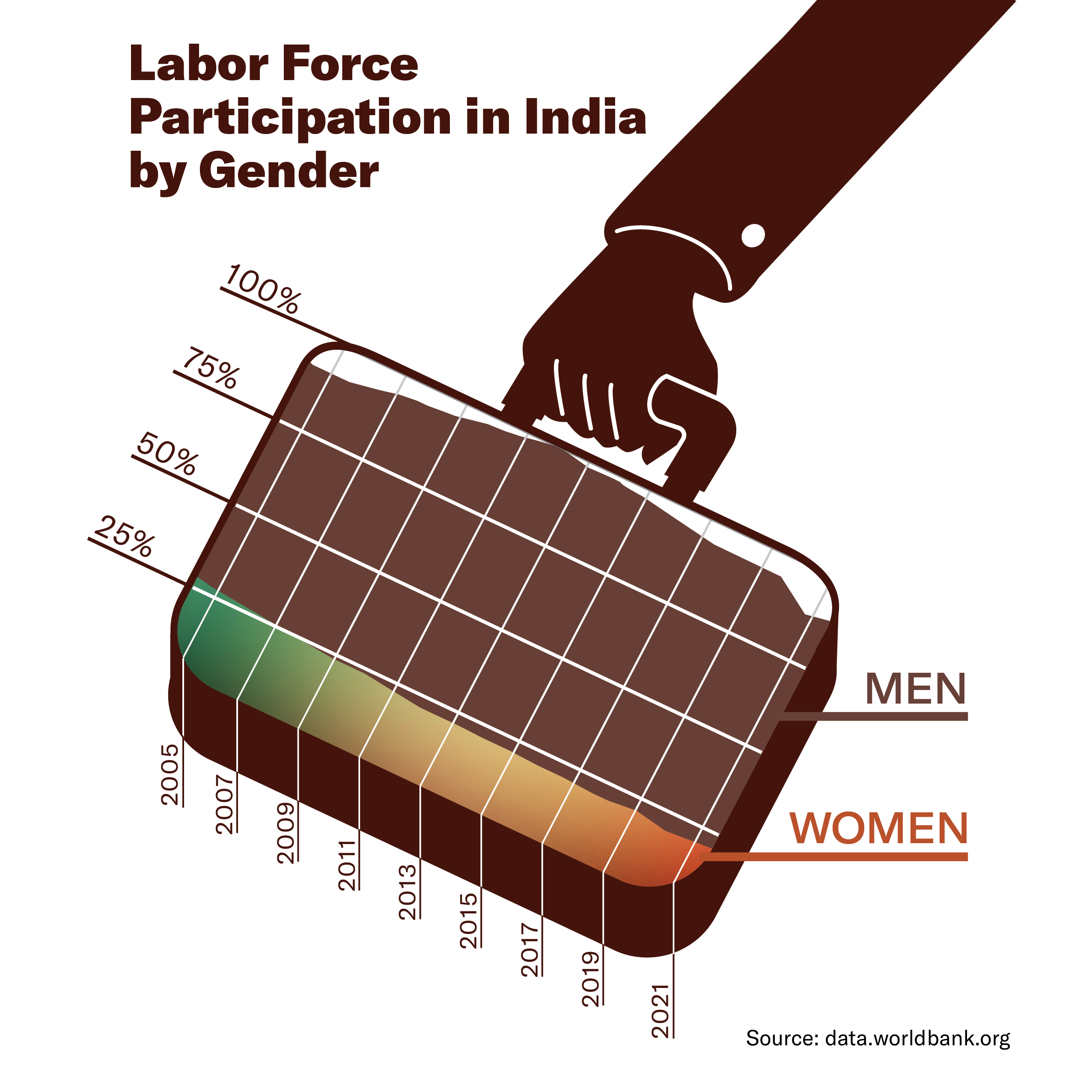

While the “time bomb” of India’s population growth has been stalled, the gap between men and women in terms of childcare responsibilities and unpaid labor continues to exist, holding the country back from true social and economic progress. Most Indians hold a relatively egalitarian view of women’s ability to govern, but still maintain rather conservative views of traditional gender roles when it comes to work.

These views stem from a deeply entrenched patriarchal culture. Indian women are taught to put others before themselves: Acquiescence to one’s father is prioritized in childhood, piety to one’s husband is emphasized in adulthood, and finally, veneration of one’s sons is expected in late motherhood. Stereotypes of domineering mothers-in-law are everywhere in Indian media, but is it any wonder that women so tightly control the family around them when they have never been allowed to have an independent sense of self? American women were similarly confined to the domestic sphere, a phenomenon dubbed the “Feminine Mystique” by Betty Friedan in the 1960s. Utilizing psychology, Friedan argued that rates of marital unhappiness and sexual dissatisfaction among American mothers were at an all-time high due to their inability to work outside the home. Sixty years later, women have overcome that obstacle in the United States but remain unable to do so in India.

Women, on average, only make 21 percent of what men do, and only 24 percent of women work in formal jobs. This does not mean that women in India do not work. In fact, it means quite the opposite. Even in western countries, women in heterosexual couples do far more domestic labor than their male partners, a gap that widens after childbirth. However, a culture of misogyny permeates Indian society, and a lack of social support means it is women who pick up the slack: They perform an average of nearly six hours a day of domestic labor, compared to Indian men who do less than an hour. This means that Indian women do more unpaid care and domestic work than women in any other country except Kazakhstan.

Rape and sexual assault is still a massive problem nationwide, over a decade after the horrific gang rape and murder of a college student in New Delhi that received global attention. While the perpetrators of that specific crime were put to justice in an extremely public fashion, marital rape remains legal and rape cases remain incredibly difficult to report, let alone convict, especially for poor or minority women.

However, attitudes are shifting amongst the younger generation, particularly women—a good sign of the social changes to come. The government can support these societal changes by holding advertisement campaigns to promote gender equality nationwide. So, too, can the wildly popular and influential Bollywood film industry, where famous actresses have already begun to speak out against the pay gap between them and their male co-stars. These changes may seem frivolous, but societal change is difficult to control, and public support from some of the country’s most popular figures can be monumental in fighting back against traditional norms.

The government can and should further promote gender equality by enforcing existing laws against gender discrimination in the workplace and legal system. While gender discrimination is officially outlawed, it remains pervasive in practice because lawsuits on the basis of gender discrimination are not often won—or even taken seriously. While meaningful enforcement is an uphill battle—particularly considering that Indian politics, police forces, and judicial systems are overwhelmingly male-dominated—women and men alike must band together to fight for equal representation.

India has defused the population bomb. However, the “problem” with defusing a bomb is that you must think about what comes next. India now has a unique opportunity to reshape its society on a fundamental level. As women turn to the workforce, India needs to ensure not only that it is safe for them to be there but also that they won’t be shamed for it. Doing so is essential to the country’s continued prosperity.