Amid the ongoing United Auto Workers (UAW) union strike at Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis, one might expect the political conversation to polarize along pro-labor and pro-management lines. Some prominent Republicans have been predictably anti-union. Presidential candidate Nikki Haley, for example, proudly labeled herself a “union buster.” Senator Tim Scott (R-SC), when asked how he would address the strike as president, fondly recalled former President Ronald Reagan’s firing of striking air traffic controllers in the 1980s. But former President Donald Trump and his populist acolytes, as well as some more traditional conservative politicians, appear willing to leave the party’s reflexively anti-labor orthodoxy in the past. The primary partisan fissure has instead centered on electric vehicles (EVs).

Trump recently predicted that “the US auto industry will cease to exist” as a result of the EV transition and that “ all your jobs will be sent to China.” Other Republicans shared this sentiment. “There is a 6,000-pound elephant in the room: the premature transition to electric vehicles,” Senator J.D. Vance (R-OH) said of the strike. The “premature transition” Vance refers to is one of the Biden administration’s key legislative accomplishments. Amid policies like tax credits for electric car buyers and investments in charging infrastructure and battery and EV manufacturing, as well as proposed automobile emission regulations, the EV market share is projected to increase from 2.4 percent of all passenger vehicles in 2020 to 17 percent in 2024. The administration aims to increase EV sales to two-thirds of all vehicles by 2032 and said in a statement earlier this year that “the path to net-zero emissions by 2050 is creating good-paying manufacturing and installation jobs on the way.”

The UAW leadership has tried to split the difference between EV optimism and pessimism. Its president, Shawn Fain, has insisted that he supports the EV transition in theory but has been disappointed by its rollout. Many EVs and EV components are being produced in anti-union, anti-worker red states after the Biden administration failed to secure a provision for more generous tax incentives for vehicles made with union labor. “These companies are taking the billions of dollars in our tax dollars, but they’re trying to drive a race to the bottom by paying substandard wages and benefits,” Fain said. The UAW is withholding its endorsement in the presidential election until Biden proves he can make the transition work for working families. But this reluctance to support Biden’s policies wholeheartedly is insufficient on its own. By aligning itself with the EV transition, even conditionally, the UAW is potentially alienating itself from the workers it exists to serve.

Auto workers seem doomed to lose regardless of which EV policy is chosen. As Republicans suggest, there is strong evidence that EVs will reduce overall employment in the auto manufacturing industry within the next few years. EVs are less complex and easier to manufacture than their internal combustion engine (ICE) counterparts: A Tesla has just 17 moving parts compared to roughly 2,000 in a typical ICE vehicle. Ford and Volkswagen estimate that this less complicated manufacturing process will require 30 percent less labor than ICE manufacturing does. “That means we will need to make job cuts,” Volkswagen’s CEO said.

The Biden administration’s goal, given this reality, is to ensure that the auto manufacturing jobs that continue to exist stay in the United States. The Economic Policy Institute, a left-wing think tank, estimated in 2021 (prior to many of the Biden administration’s major EV policies) that, without government support for domestic EV manufacturing, the auto manufacturing sector could lose over 75,000 jobs by 2030. With government support, however, the industry could gain over 150,000.

But the federal government cannot prop up the American auto manufacturing industry forever. The Biden administration can only justify giving someone earning six figures a $7,500 tax break on their new Tesla due to the existential threat of climate change. Once EVs have penetrated the market and the United States has successfully transitioned to clean energy, the federal government will feel considerable pressure to discard climate-protective EV subsidies. As a result, jobs will be shipped back overseas where cars can be produced more cheaply. The United States may end up with a similar slice of global auto manufacturing, but in a transformed industry that employs fewer people. If Republicans kill federal support for the domestic EV manufacturing industry, though, EV jobs may never come to the United States in the first place. The prospects for auto workers look grim.

Given these facts, it is fair to wonder why the UAW is supporting the EV transition at all. In part, it is likely that Fain feels a genuine moral obligation to wield his power in a way that avoids threatening the planet’s future and promotes a transition away from fossil fuels. But the UAW’s conditional support for the EV transition is also a political calculation. Fain would almost certainly publicly condemn the Biden administration’s support for EVs if the labor movement was traditionally associated with the Republican Party and, reciprocally, Republicans supported pro-union and pro-worker legislation. The movement’s close alliance with the Democratic Party is likely factoring into the UAW’s position, which seems calculated to demand more of the Democratic Party without besmirching one of its recent legislative accomplishments. This would risk the UAW’s demands falling on cooler ears at the White House, which might make it more hesitant to continue investing as much as it has in protecting auto manufacturing jobs. President Biden certainly would not be joining the UAW picket line.

But the labor movement cannot afford this kind of political operation right now. Unions are on life support. Private sector union membership has dwindled to just 6 percent from roughly one-third of the US workforce in the mid-1950s, largely a consequence of a union organizing process stacked against unions and favorable to union-busting corporations.

American workers’ lack of trust in unions has also likely contributed to this decline. The perception that unions function more as progressive advocacy groups than collective bargaining coalitions is at the core of this distrust. The UAW, and the labor movement more broadly, cannot allow any doubt that it is fighting for its workers and not a progressive agenda in Washington. There is clearly already some rank-and-file resentment toward UAW leadership, evidenced by the auto workers who showed up to the Trump rally to hear him rail against EVs and union leadership. If the UAW, a famously powerful union, can lose the trust of its own members, convincing skeptical prospective union members to enlist is likely to be an uphill battle. Fain’s calculation makes good political sense in the short term but risks undermining the UAW’s authority and the legitimacy of the labor movement.

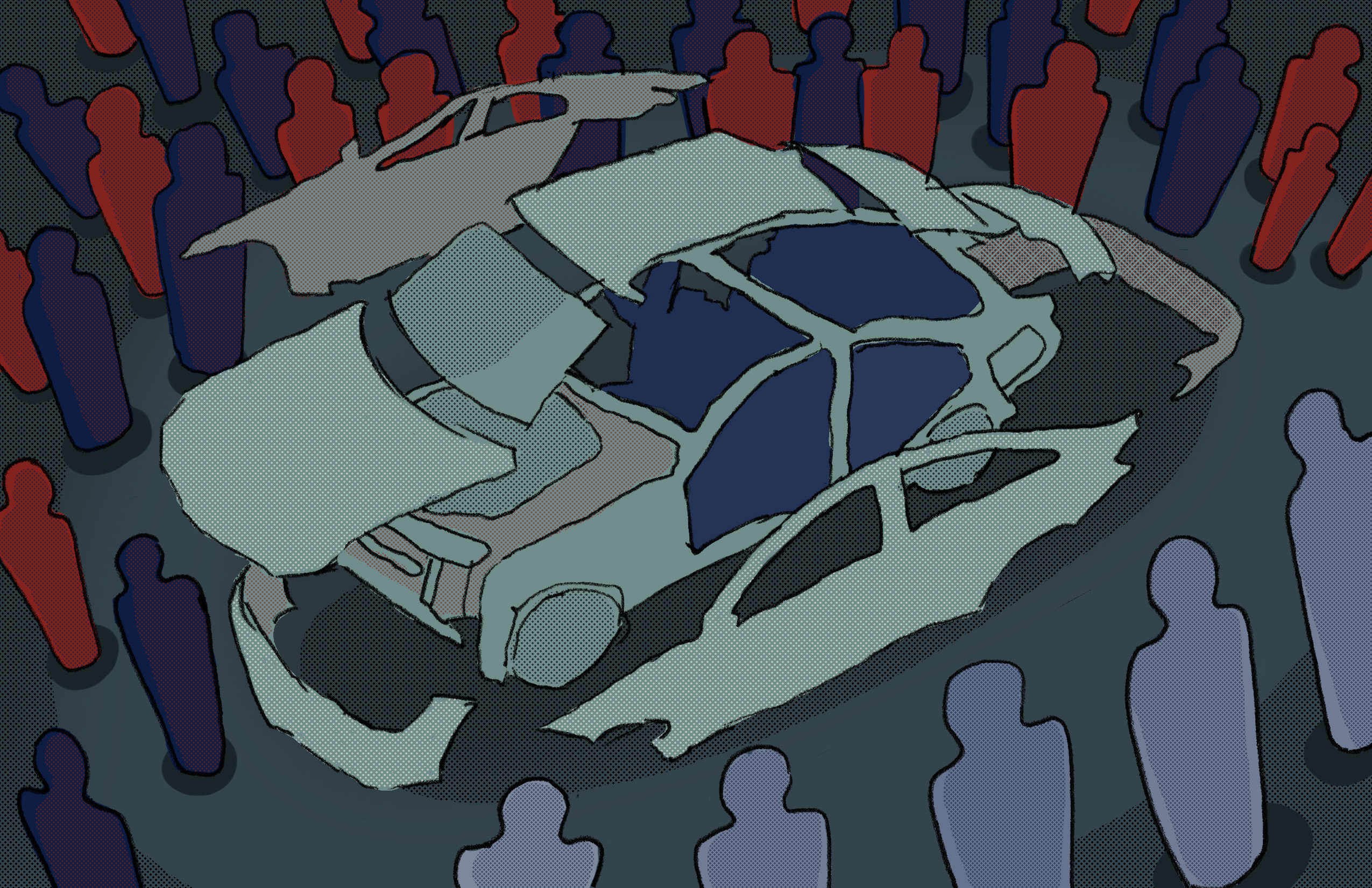

The UAW’s current approach—conditionally supporting Democratic policies to hasten an EV transition that is expected to hurt auto workers in the long run—thus carries substantial risks to the credibility of the UAW and the labor movement as a whole. The alternative—aligning more with Republican rhetoric and trying to impede the inevitable shift to EV production—could doom the American auto manufacturing industry. The UAW would be betting it all on horse-drawn carriages just before the advent of Ford’s Model T. How, then, should the UAW move forward?

Political parties cannot be expected to fully represent the interests of a constituency as narrow as auto workers. Only unions can. The UAW’s best option is to forge its own nonpartisan path. It needs to acknowledge the inevitability of the EV transition and the harm it is likely to cause to American auto workers and, with this reality in mind, demand that automakers and the federal government look after their needs now and in the future. Pretending the problem has a simple solution, especially to protect a political alliance, does not serve auto workers or the labor movement. To successfully navigate the EV transition, the UAW needs to talk straight and not place partisan politics over its members’ welfare.