What’s the difference between a Marxist newspaper and a Brown student’s for-you page? This isn’t the beginning of a joke. Say that both challenge the status quo and both in the same way. Are they different at all? And if we agree that no government should burn the Marxist newspaper, isn’t cracking down on the ‘political echo chamber’ a violation as well?

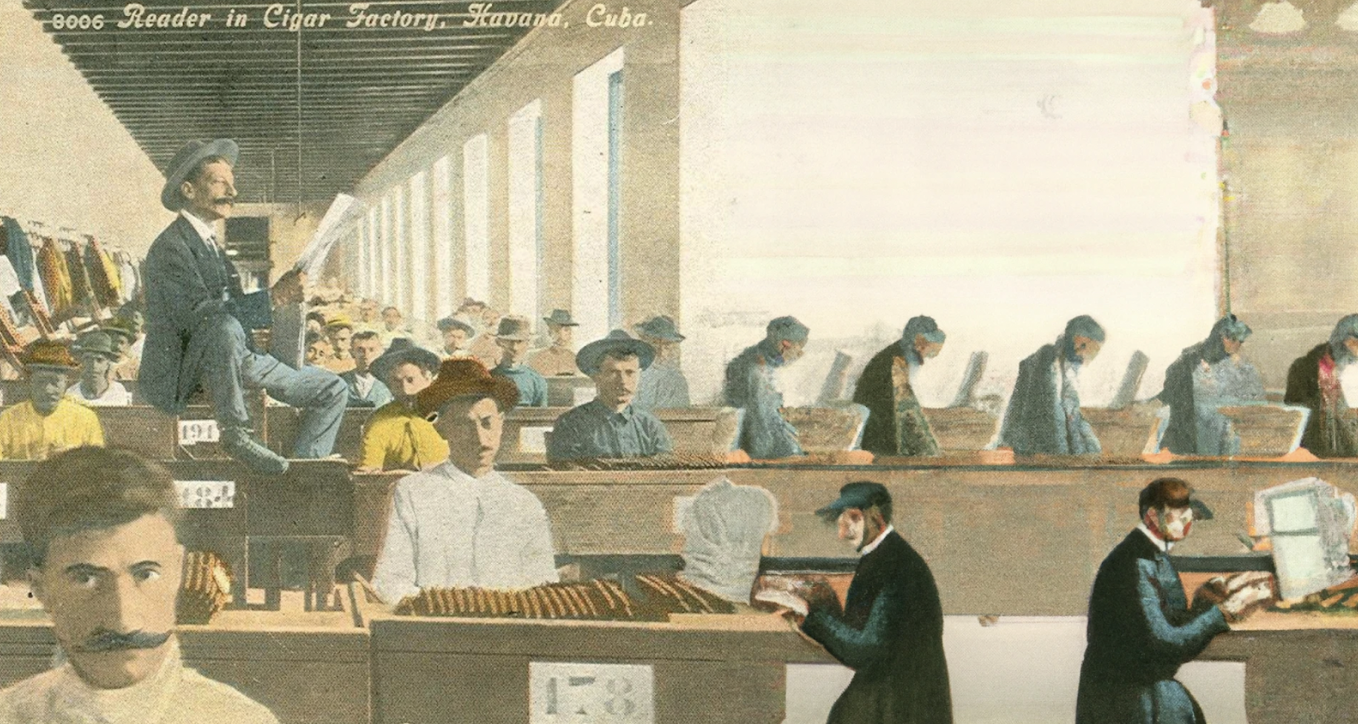

In theory, access to disruptive content strengthens democracy. A century ago, the link would have been obvious. The average progressive-era American was remarkably well read—blacksmiths and cigar makers paid children to read Milton or Marx on the factory floor as weavers propped newspapers behind their looms. It is no coincidence that that period witnessed the broadest social movements in labor and gender-equality up to that point. Put differently, subversive material not only strengthened civic engagement, it actively built a more equal society. So why doesn’t ours?

As media targeting gets more effective, subversive content serves an increasingly less productive function, weakening intellectual engagement and with it our ability to pragmatically resist the status quo. Remember the weaver and his newspaper? At his corner newsstand, he picks from a few options: Reynolds News, John Bull, the Daily Herald, and the Northcliffe Press. Each one is the product of marketing strategies and company initiatives to increase engagement. But the weaver, intimately familiar with the papers, knows their tactics—John Bull’s “scandal-mongering” and the Northcliffe Press’s “cliches and catch-phrases.” More importantly, he knows their biases.

This isn’t conjecture: In 2001, Dr. Jonathan Rose exhaustively cataloged 19th-century British working-class autobiographies, finding that wide newsstand selections “made people uniquely aware of the differences between varying types of publications.” Even 100 years later, the average person might have knowingly switched from CNN to Fox and back, careful to contextualize their respective biases. But cable TV is dying.

Its successor, the personalized media machine, drowns the user in a sea of consensus, disguising the existence of bias altogether. The for-you page diagnoses its user as a Marxist and never shows them a Tucker Carlson snippet again. Of course, to the user, it seems as if they are seeing the whole picture.

At best, the user becomes increasingly unable to defend their own opinions; at worst, they become unable to distinguish good information from bad. If subversive content used to challenge people to think differently, its role in society today is decidedly less productive. Intellectuals may still invest time to read widely and examine their assumptions, but the casual QAnon believer or Bernie Sanders Reddit-poster questions less, growing complacent in their own subversive bubble. There are a hundred possible ways to resist the status quo, but my phone only shows me one.

Better marketing has an impact on the content too. The subversive ideas most likely to propagate in an age of 10-second attention spans are often overly simplistic and likely to elicit deep emotional responses. The result is predictable: narrow social movements that paint the world in stark, categorical terms. Unlike the 19th-century social movements in organized labor and suffrage, which sought to persuade opponents in the direction of compromise, the movements of the 21st century have no room for compromise and little understanding of the other side.

Proponents of media targeting blame the user. To them, personalized learning models merely reflect desires. If a user wants to see only content he agrees with, who is his computer to tell him differently?

Let’s go back to 19th-century Britain. The same autobiographies that lauded the importance of understanding bias have another shared characteristic. After the individual’s first jump from the penny-dreadfuls to political literature, they reference a moment of epiphany. In the words of 19th-century worker Walter Hampson, “I quickly discovered my limitations, resolved to gain some knowledge, and began the pilgrimage of the ignoramus.”

People are naturally driven to question the status quo. It may also be true that on some level, we crave consensus, even within the subversive content we subscribe to. But people are naturally hungry and may also crave sweets. Does this imply that dessert is the ideal diet? Of course agreement feels good. Biologically, it represents progress—the resolution of different ideas before the creation of a plan. But what opposing ideas have ever been resolved on a for-you page?

So we get the feeling of agreement but none of the societal progress agreement usually entails. If the reader of the Marxist newspaper, upon finishing this week’s edition, might have picked up the conservative John Bull, our generation’s for-you page offers no such respite. It is a mainline shot of dopamine, expending all that curiosity on one-sided, subversive conspiracy theories.

Subversive content in our hands used to strengthen democracy. In the hands of the personalized media machine, it does the opposite. When, at some point in their life, the average user feels at odds with the status quo and desires to effect change, they will find themselves declawed—unequipped to sustain productive disagreement or to find common ground. The personalized media machine has made us weaker debaters, reformers, rebels, and compromisers: It has made us worse citizens. In a strange sort of way, the same content which might have galvanized change a century ago has rendered pragmatic opposition impossible today.