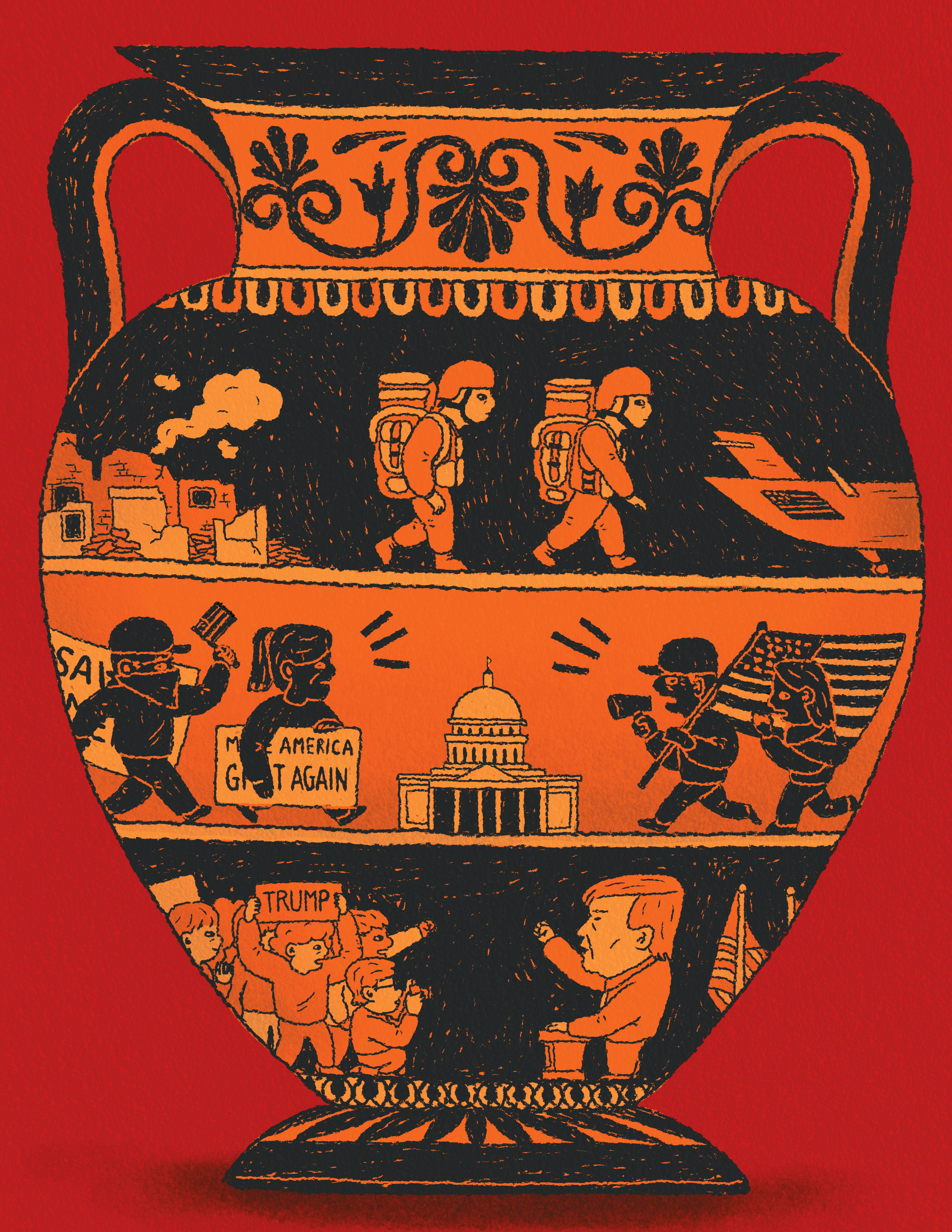

How often do you think about the Roman Empire? An online trend has unearthed an ancient obsession. In September 2023, Google data showed an all-time high in searches for the “Roman Empire,” while videos tagged #RomanEmpire amassed about three billion views on TikTok. Today, as doomsayers anxiously predict America’s decline, we return to the question of Rome. To most, the ‘Fall of Rome’ conjures apocalyptic images of violent hordes storming the gates of the Eternal City––an ancient, bloodier January 6. But Rome did not fall in a day. Over the centuries, a slow decay gnawed at the Empire’s fabric, weakening it to the point of ‘catastrophic’ collapse in the West. Is America doomed to the same fate? Confronted by a rising China and wars in Europe and the Middle East, the Pax Americana is facing its greatest test. What foreign policy lessons can America draw from the Roman Empire?

Thucydides’s Trap, a theory advanced by Graham Allison, argues that when a rising power threatens to displace a hegemon, the result is usually war. Rome’s ascension followed that script: The Punic Wars saw the burgeoning Roman Republic challenge its North African rival Carthage, culminating in the complete destruction of the latter in 146 BCE. Similarly, Imperial Japan challenged the United States in World War II. The result was Japan’s devastation and American hegemony in the Pacific and Atlantic. Great power contests were thus the crucibles of Roman and American power. Today, as China weighs an invasion of Taiwan, the United States may be lured into Thucydides’s Trap. As the incumbent superpower, does the United States stand to gain more from preserving the status quo or from preemptively confronting China while it maintains a military advantage? Could conflict with China, as some hawks argue, actually reinvigorate the United States as in 1945—in this way avoiding the fate of Rome? In the nuclear age, this may be too costly to ponder.

During the Pax Romana (27 BCE – 180 CE), Roman citizens enjoyed a period of relative stability and economic prosperity within the Empire’s borders. However, this “peace” did not extend to Rome’s frontiers. Unlike America, Rome did not have the luxury of oceans separating it from its enemies: From Scotland to Syria, the army was at constant blows with non-Roman, “barbarian” peoples. Similarly, Pax Americana is a peace for many but not all. Since 1945, the US Army has staged major interventions in Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq, as well as covert operations across the globe. Though not an empire in the Roman or British sense, the United States has an unprecedented military reach.

As Roman historians will testify, imperial hubris can cause superpowers to overstretch, uniting their enemies and creating costly distractions. The 3rd and 4th centuries saw Rome wage wars on two fronts: to the North with Germanic tribes and to the East with the Sassanid Persian Empire. Humiliating defeats at Edessa (260 CE) and Adrianople (378 CE) forced Rome to retreat in both directions. By the 5th century, Rome could no longer repel the successive waves of barbarian incursion. When the Visigoths sacked Rome in 410 CE, it dealt a psychological blow from which the Romans never recovered. A little like New York on 9/11, the city of Rome had not been attacked by a foreign power in centuries. There are, of course, limits to this comparison. But when Osama Bin Laden shattered Americans’ sense of security in 2001, he dragged the United States into two ultimately humiliating foreign wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Hence, a pattern emerges: If big wars build empires, smaller military adventures weaken them.

The two-front expansion that forged the Pax Americana now presents myriad challenges. Like Rome, the United States has had a unifying effect on its enemies, with China heading a loose coalition of anti-American autocracies including Russia, Iran, Syria, and North Korea. With its vast network of alliances, the United States caters to a roster of military aid recipients. In October 2023, President Biden asked Congress for $106 billion in supplemental national security spending to aid Ukraine and Israel. America generally sends different weapons to Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan, but their needs sometimes overlap. According to The Economist, a conflict over Taiwan would quickly deplete America’s stock of long-range anti-ship missiles, the weapon “most useful in repelling an invasion.” As seen in Rome, military hegemony can sow the seeds of overstretch and eventual retreat.

To state the obvious: America is not Rome. Foundational concepts like human rights, the separation of church and state, and centralized banking would be completely alien to the Romans. American presidents worry about re-election, not death on the field of battle. Nonetheless, our comparison yields three connected lessons for American foreign policy: Great power conflict strengthens nations, and small wars weaken them; superpowers at their peak sow the seeds of their own decline; and military overstretch can have catastrophic effects on security. Can shrewd foreign policy see off threats and prolong the Pax Americana? Surely. Can it alter the course of a global tectonic shift towards multipolarity? That remains to be seen.