When asked about the United Arab Emirates’ economic trajectory, Dubai founder Sheikh Rashid al Maktoum responded, “My grandfather rode a camel, my father rode a camel, I drive a Mercedes, my son drives a Land Rover, his son will drive a Land Rover, but his son will ride a camel.” The Sheikh’s generational tale reflects a growing concern in oil-rich countries—that the global demand for petroleum will soon dwindle. As the world’s largest petrostate, Saudi Arabia is in a particularly precarious position: Its economic and geopolitical leverage hinges on Western oil and natural gas consumption.

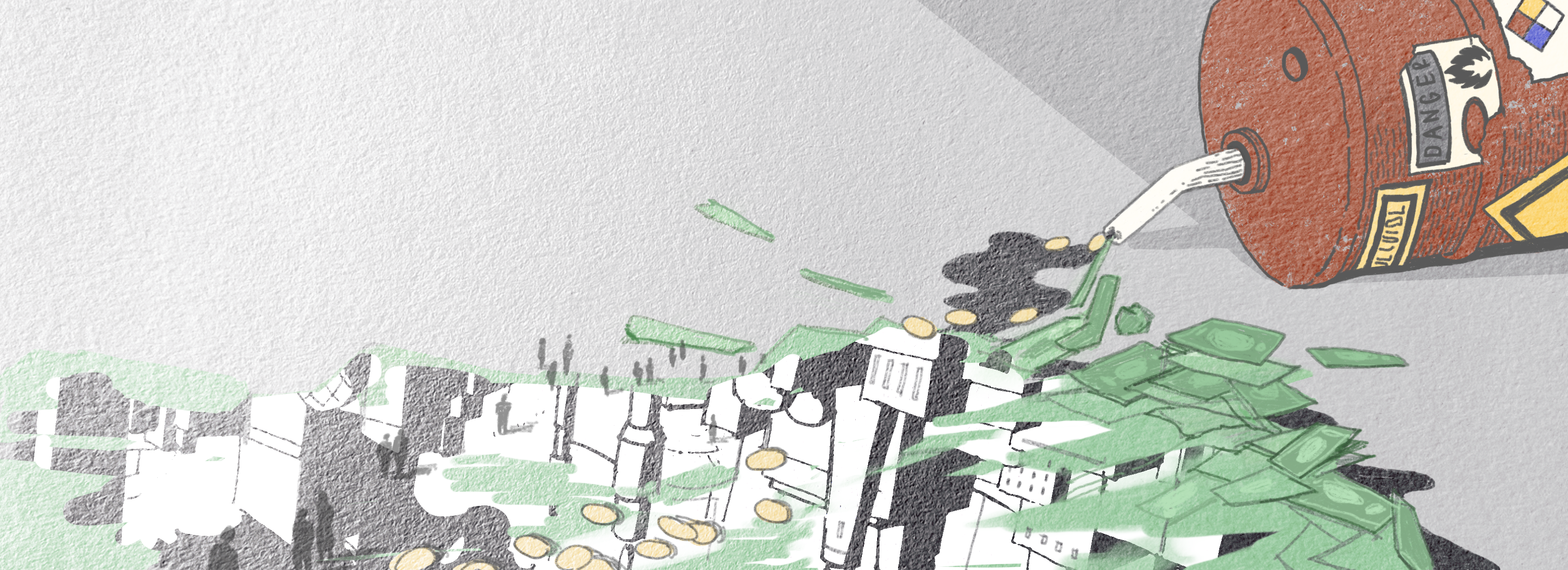

With the projected decline in global oil use threatening its influence, the Saudi government is seeking alternative methods to bolster its economy. It has settled on championing massive tourism projects that aim to attract both foreign visitors and international investors. The most notable example is the $500 billion smart city in Neom dubbed “The Line,” a 170-kilometer-long urban space with futuristic trappings like artificial intelligence surveillance and three distinct “layers” for pedestrians, infrastructure, and transportation. But in the absence of American oil dependence, Saudi Arabia’s industries will no longer be shielded from the backlash against their human rights violations and environmental crimes. While an increase in tourism may make up for some of the country’s economic shortfalls, the country and its excessive megaprojects will be unprecedentedly vulnerable to international scrutiny.

For nearly a century, the United States, reliant on Saudi oil, has largely ignored the Kingdom’s human rights abuses and environmental wrongs. As Ellen Wald, a historian of Western interference in the Middle East, noted, “The Saudi government has routinely violated human rights—barring Jews, prohibiting free religious practice of Christians, permitting slavery, subjugating women, prosecuting journalists, arresting clerics and princes, and locking up feminists for ‘treason’—with minimal pushback from the United States.” Despite not viewing Saudi Arabia as an ally state per se, the US government recognizes that Riyadh is a transactional partner to work with for massive economic and geopolitical benefit. An agreement signed in 1945 cemented this symbiotic relationship. Over the course of an hours-long meeting, then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt struck a deal with Saudi King Ibn Saud: Saudi Arabia would supply the United States with oil, and in exchange, Washington would provide the Kingdom with arms and security.

Since then, the United States, committed to its oil interests, has come to Saudi Arabia’s defense numerous times, both militarily and on the international stage. That defense is conditional, however. In 2019, for example, the United States failed to sufficiently respond to an Iranian missile and drone strike on Saudi oil fields. Why? Because doing so would have threatened the global petroleum market. When protecting the Kingdom threatens American oil, Washington has historically refrained from intervening.

President Joe Biden’s pledge to reduce US reliance on oil—along with the West weaning itself off of fossil fuels more broadly—spells trouble for Saudi Arabia. What will happen if the Kingdom continues to violate international norms, only this time by investing in newfangled tourism projects like The Line?

On February 6, the Neom project opened an office in New York City, a sign of its hope to garner American investment. Referring to this new venture, Neom CEO Nadhmi Al-Nasr stated, “Neom has already established many investments and partnerships with U.S. entities, and through this office, we intend to build our relationships among key industry verticals and business sectors.” The Line is not just relying on the United States and other Western investment outlets to subsidize its $500 billion construction cost: Once built, it will depend on Western tourists to stay economically afloat. To attract such investment and tourism streams, the Kingdom will have to adhere to American rules more strictly.

Economic dependency thus runs the other way in the tourism industry—Saudi Arabia will rely on Western support to sustain its attempts at developing this new economic sector. Consequently, with the fall of the oil shield, Saudi Arabia will be forced to appease the Western-led international system, as public criticism could negatively impact both tourism and foreign investment. By betting its future on a tourism economy, Saudi Arabia is forsaking the immunity it once enjoyed.

And yet, The Line remains an environmental and human rights nightmare, incapable of insulating itself from the scrutiny the oil industry avoided. As Philip Oldfield, Professor of Architecture at the University of New South Wales, argued in an interview for this article, “Creating any new city for nine million people would likely have an enormous impact on the environment. If we were to rebuild London or New York right now, it would involve millions of tonnes of concrete, steel, aluminum, and subsequently, greenhouse gasses.”

From a human rights perspective, the project is not much better. In fact, last May, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights released a statement criticizing Riyadh for the mass displacement of people indigenous to the area around the construction site. The statement also condemned the Saudi decision to give death sentences to three men who allegedly protested their forced relocation. Saudi Special Forces reportedly killed another protestor in his own home. Saudi Arabia has thus far failed to adapt to its new, less-advantageous political position.

For now, US reliance on oil remains intact—Saudi Arabia still exports almost $300 billion worth of petroleum each year. However, the diminished relevance of the oil-for-protection quid pro quo will disincentivize the United States from shielding Saudi Arabia from normative criticism. In fact, as a global hegemon that rhetorically centers the international system around freedom and human rights, the United States actually has an incentive to criticize Saudi behavior and punish the government more openly.

As global dependence on oil decreases, it is only a matter of time before Saudi Arabia will need to comply with the global norms it has often shirked in the past. The Saudis must develop a political savvy that prioritizes restraint over abuse and incorporates the expectations of the international system. Their current behavior—emphasizing excess at whatever human rights and environmental costs—will not be able to subsist without oil as a key bargaining chip.