“With a goat’s horn and bazooka at our necks. Sending heads flying if anyone gets in the way. We’re bloodthirsty, crazies deep in the scene. We like to kill.”

Accompanied by the sounds of accordions, guitars, and AK-47s, these are the typical lyrics of Los Buknas de Culiacán and El Komander, two musical artists who have glorified the Mexican drug trade through songs known as narcocorridos. Together, they have amassed over 37 million views on YouTube and filled concert venues across Mexico and even in parts of the United States. Corridos first came to popularity at the height of the Mexican Revolution, providing an outlet to recount the hardships and victories of the movement as well as leaders like Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata.

Today, corridos serve as a news source, detailing stories of cartel leaders, their executions, and the violence they create on both sides of the border. When Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, one of the most infamous drug leaders, escaped Mexico’s maximum-security prison in July 2015, musicians quickly composed corridos about his escape that criticized the federal government’s inability to defeat the cartels. Between the 2007 onset of Mexico’s military intervention against the cartels and the end of 2014, there were 164,000 homicides in the country, 55 percent of which can be attributed to the drug war. This continuing struggle, and consequent suffering, provides ample material for narcocorrido performers.

Drug leaders often commission songs from these musicians for up to $15,000 in an effort to promote their reputations. Such services, however, have turned musicians into pawns in the turf wars and rivalries that dominate the drug conflict. Singer Javier Rosas, for example, was shot and left in critical condition in Culiacán, the base of the notorious Sinaloa Cartel. Similarly gruesome tragedies have prompted many city governments, like that of Chihuahua, where a concert shooting left two dead, to institute a ban on the performance of the narcocorridos. Punishments include a fine of $20,000 and up to 36 hours in jail.

Because the federal government must respect freedom of speech, it has left lower governments to battle the influence of the narcocorridos on their own. Since as early as 2001, states have monitored musical groups for their connections with cartels and have negotiated bans with radio stations. Los Tucanes of Tijuana, which has reached international fame with noncartel related songs, is no longer allowed to play in its home city after paying tribute to Raydel Rosario López Uriarte, a hit man and high ranking member of the Tijuana Cartel. However, states rarely enforce these bans or raise any specter of censorship.

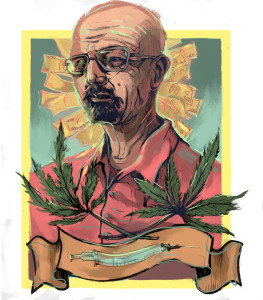

Narcocorridos are just a microcosm of the broader narco-culture that exists in communities in Mexico. Despite efforts to minimize the influence of drug traffickers, narco-culture has permeated the lives of Mexicans and people across the world. Documentaries, such as “Narco Cultura,” which follows the life of a narcocorrido performer, and “King of Shadows,” which offers insights on the conflict from the perspectives of a Catholic nun, a former drug smuggler, and a Homeland Security officer, attempt to help audiences understand the complexity of the drug wars and the culture they have created. However, more individuals watch so-called binge-worthy television shows related to the drug war like “Narcos” on Netflix, “El Cartel” on Telemundo, or “Breaking Bad” on AMC. The exploits of these drug kingpins seem like a faraway fantasy for many viewers, but for Mexican people living in areas greatly affected by the drug trade, such as Sinaloa and Tijuana, these depictions are the frightening reality.

The cultural phenomenon of narco-culture is indicative of a larger political problem at hand. The glorification of drug cartels has filled the vacuum left by Mexico’s failing government, which many say should be providing education and jobs instead of prohibiting music. Since the country’s political institutions do not support the people, drug cartels have swooped to the rescue of Mexican communities, providing economic opportunities, stability, and hope for a better life.

One key demographic affected by narco-culture is young adults in Mexico, who are hit the hardest by unemployment and wage stagnation, perhaps explaining the lure of informal economies like the drug trade. In 2014, 85 percent of adults between 20 and 29-years-old earned the lowest wages in the nation at $450 or less per month. Of the 8.3 percent of young adults that are unemployed, as many as 15 percent are college graduates. Since the global economic crisis of 2008, the lack of available jobs and the limits of the education system have led to the emergence of a class of young adults known as the ninis, a pun on the Spanish word for “neither,” because they neither work in the formal economy nor attend any type of educational institution. While the government has attempted to lessen the barriers to entry into the labor market with measures such as tax incentives for companies willing to hire young adults and short-term training courses, these attempts are not enough to solve the problem — a mismatch between the skills of young adults and the available positions persists, a concern compounded by the low education rates that characterize the group. As a result, the prevalence of drug trafficking has provided an easy and lucrative alternative for young adults that are in urgent need of income. For example, ninis in Juarez are paid $45 for a hit, an amount equivalent to the weekly average income of a worker in this city, once named the murder capital of the world due to cartel violence. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México asserts that there are millions of these ninis who are more exposed to these illicit career opportunities than ever.

Kingpin El Chapo’s own personal history is emblematic of the dreams nurtured by many of the ninis. He was born and raised in a destitute rural town by an abusive father who also traded drugs. By the time he was a teenager, he was kicked out of his house, eventually joining the drug trade. Through growing and selling marijuana, he managed to survive financially and start his empire, amassing a net-worth estimated to be $1 billion in 2016. Like many other high-ranking cartel members, he’s the epitome of a self-made man, starting off with no money and an urge to break the cycle of poverty. Especially when romanticized by popular music, stories of such success and wealth can offer an alluring alternative to Mexicans who feel like they have few other prospects.

The influence of narco-culture is far from limited to teens and young adults that make up the ninis; the drug trade also attracts children at a young age. Cartel members dangle promises of a better life to easily recruit children — desperate for money and social capital — to transport drugs and conduct key jobs for the cartel. The sheer number of young people implicated in the drug trade is staggering: The Child Rights Network in Mexico has indicated that about 30,000 children are involved in some sort of criminal organization. In one case, a 14-year-old boy was found guilty of torturing and beheading four people on behalf of one of the Mexican cartels, a startling but hardly rare occurrence. Another young girl, working for the Zeta cartel, earned about $800 a month before being caught for committing crimes on the Zetas’ behalves. In the city of Guerrero, which the governor has compared to Afghanistan for its prime production of opium, cartels enlist children to harvest the poppies for heroin. Many teenagers have also become mules for local drug traffickers, traveling across states and borders to deliver drugs from marijuana to methamphetamines. The US Immigration and Customs Enforcements states that the number of youths aged 14 to 18 that have been caught crossing the border has increased greatly. In 2008, 19 minors were arrested, while in 2011, the number increased ten-fold to 190.

With inadequately developed criminal justice procedures for youth, the government has failed to effectively respond to this type of child abuse. About 5,000 minors, most of whom come from low-income households, are currently in Mexican prisons, with over 1,000 of them arrested for committing serious cartel-related crimes. Deputy Alejandro Sánchez Camacho indicated that 22 percent of incarcerated youth have killed at least one person among other violent crimes. In 2015, the United Nations concluded that the Mexican government is taking insufficient measures to prevent the cartel recruitment of children and adolescents. For one, there’s a startling disregard for the children’s privacy: When these children are arrested, authorities oftentimes present them to the media without permission. Moreover, incarceration doesn’t seem to solve the core of the narco-culture issue; instead, as the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child has advocated, it’s necessary to promote educational and social treatment for these juvenile delinquents so that they can be given the tools necessary to live outside the illicit sector.

There’s evidence of a less explicit influence of the drug wars on Mexican childhood. Children increasingly mimic the actions and structures of organized crime groups, threatening each other for money on the playground or yelling obscenities to each other during soccer games. Exposure to violence is perhaps changing the way youths perceive their own futures and their opportunities for success. The ubiquity of music romanticizing the life of drug kingpins makes it easy for children to see such lifestyles as alluring. Not only does the public image of this profession convey an image of cartel members’ financial stability, but also the popularity of narcocorridos. For instance, implies that the life of a drug kingpin is often a life of respect and adoration.

Even without the help of narcocorridos, cartel leaders are still often admired as modern-day Robin Hoods at the lowest ends of the socioeconomic ladder. By offering welfare of sorts to impoverished residents, the cartels have undermined the already failing government. In Sinaloa, for example, El Chapo has helped poor communities by providing money for infrastructure and jobs, thus earning the trust of the state’s residents by helping the community when the government has not. After his recapture in 2014, vendors printed shirts with El Chapo’s face and hats reading “God Save El Chapo.” Such narcomoda, or narco-fashion, is also prominent in Mexico, exemplified by jewelry depicting drug paraphernalia and similarly styled brand name clothing. In 2011, for example, street vendors stocked their shops with Ralph Lauren “narco polos” that were worn by high-ranking drug traffickers when they were arrested. This type of style is popular among lower classes, members of which have grown to idolize the drug lords, partially as a result of the social and economic aid that the cartels grant to poor communities.

Likewise, even religion cannot escape the tendrils of narco-culture. When El Chapo was recaptured in 2014, many Sinaloans took to prayer. Jesús Malverde, a 20th Century Mexican bandit who used money generated from illicit activity to support impoverished communities, just as El Chapo does today in Sinaloa, is the patron saint of drug trafficking and criminal activity. Although not recognized by the Catholic Church, many people, especially those in poverty, petition him for financial security and protection. Malverde’s products like prayer cards, candles, and statues can also be purchased across Mexico and in some US cities — but he is far from the only so-called “narco-saint.” Santa Muerte, or Saint Death, is a combination of the Virgin Mary and the Grim Reaper, who also serves as a patron for drug traffickers. While the Catholic Church has called the cult of Santa Muerte “blasphemous, diabolical, and anticultural,” her following continues to grow — Mexican religious shops sell more Santa Muerte figures than those of the Virgin of Guadalupe, the patron saint of the nation. Drug lords also cultivate ties with local churches; some even refer to El Chapo as the patron saint of Culiacán, the capital of Sinaloa. The altars of Jesus Malverde and Santa Muerte have been joined by icons and objects of El Chapo.

Narco-culture has affected nearly every aspect of Mexican culture, from children’s games to fashion trends to religion. While the negative effects of such glorification of drug culture and violence on youth are obvious, the prevalence of narco-culture is indicative of the larger political problems at play in Mexico. The vacuum left by government failures has allowed cartels to dominate life across the country. And until political reforms take place, cartels will continue to get richer, musicians will continue to sing about their success, poor Mexicans will continue to idolize narco-saints, and malcontent youth will continue to lose themselves in dreams of riches.

Art by Tiffany Pai