Cuba is home to over 2,800 beekeepers, who collectively control around 180,000 hives. Over the last 30 years, organic honey has grown into the nation’s fourth most valuable agricultural export, bringing in more foreign currency than either coffee or sugar. A liter of the island’s “liquid gold” costs more than a liter of oil. As pollinator populations fall across the globe, Cuba’s hives are all the buzz. But while the island’s warm climate exempts it from the winter frost that kills 20 percent of colonies in colder regions, its geographical advantage does not fully explain the industry’s growth. A closer look into Cuba’s apicultural paradise reveals the grim forces—politically enforced poverty and labor suppression—that enabled its rise and presents a dilemma for conscious consumers.

The Cuban honey market is a fascinating paradox of market economics. When the Soviet Union collapsed in the 1990s, farmers on the island lost access to modern fertilizers and pesticides. An American embargo also prevented growers from buying and using foreign chemicals, which made the island’s natural flora healthy and lush for bees. Beekeepers around the world have expressed concerns over the impact of agricultural chemicals on roaming bee populations. But not in Cuba. While other farmers may struggle with optimizing yields, the island’s apiarists benefit from the organic vegetation surrounding their hives.

Cuba’s adoption of organic farming practices has contributed to the soaring popularity of its honey industry. Consumers usually purchase organic products because they feel that in doing so, they are eating healthy or helping the environment, given that organic foods are often marketed as the edible manifestation of harmonious coexistence between man and nature. Cuba has certainly taken advantage of this image: In 2018, 1,900 metric tons of its honey (one ton is equivalent to 2205 pounds) were certified as “organic”—a national record. Organic honey is more profitable on the open market than non-organic alternatives; ordinary honey sells for $4,600 per metric ton, while organic honey can sell for up to $14,000 per metric ton. In this way, Cuba’s lack of access to international markets has given its honey a competitive edge.

Despite these advantages, the “organic” label on Cuba’s honey obscures the bleak reality of the workers behind it. Cuban apiarists cannot sell their produce on the open market. Instead, they must exchange their crop with a state-run company, Apicuba. When they do attempt to circumvent the state and sell their honey independently, producers are penalized heavily; the Cuban government flexes the power of its monopoly by enacting massive efforts to crack down on the underground market.

Cuban apiculturists are truly at the mercy of the state. A closer look reveals that its drivers are not nearly compensated enough for their labor, making life even more difficult for citizens of a country already cut off from international monetary flows. The government monopoly often shortchanges producers for their services, forcing them to sell at around $600 a metric ton while exporting their organic crop for as much as $14,000 (a markup of over 2300 percent). In addition to this shocking discrepancy, the Cuban government rarely adjusts compensation for producers to reflect fluctuations in the international price of honey, further capping workers’ already meager compensation.

Furthermore, the frequency of environmental disasters compounds workers’ hardships. In 2016, Hurricane Irma decimated the industry’s production capacity and destroyed large swaths of flora. Since replacement capital could only come from the government, farmers had fewer opportunities to adapt and resume production.

Although the Cuban government’s actions are clearly exploitative, change is difficult, partly because of how little say workers have over their payment scheme and production opportunities. Apiarists with more than 25 hives are mandated to join “collectives,” which organize their production and provide machinery and other capital. This forced reliance on the government, not to mention the complex bureaucracy attached to it, makes it difficult for workers to pursue late payments. “They pay us when and how the company wants,” explained a disgruntled beekeeper. “The payments take months and the resources we requested never arrive.”

Despite the fact that beekeepers are treated like public employees, they often incur massive out-of-pocket costs. Hives are usually distant from the producers’ homes, so apiarists must rent vehicles to access their farms, a cost that comes from their already shallow pockets. Although it is true that Apicuba provides equipment and discounts for inputs such as fuel, these perks do not always arrive on time. Such delays pressure farmers to procure necessary equipment by taking out loans from banks, some of which are owned by the state. By these methods, the Cuban government profits immensely from its honey, yet those who actually produce it do not share these gains.

These troubling conditions for workers have not dissuaded consumers from purchasing what they perceive to be a superior product. Recently, the popularity of Cuban honey has surged in Europe: Germany, France, Spain, and Switzerland top the list. On the island, officials have announced further plans to expand into Chinese and Saudi Arabian markets. Last year, the island produced 8,834 metric tons of honey, 1,500 metric tons more than Apicuba’s target. While the overall output is small compared to other giants such as China and Turkey, the government opened a new bottling facility to increase output to 15,000 metric tons a year. The state also plans to diversify its portfolio by selling honey byproducts such as beeswax.

Clearly, there is no sign of the industry slowing down. The Cuban honey industry should not mask its problems with the ideals of environmental sustainability and worker empowerment. The former is reinforced by external political conditions, and the latter is simply a myth. This reality does not necessarily warrant boycotts or sanctions—such measures would only cut Cuban apiarists off from their lone source of income. But as the industry continues to expand consumers will have to grapple with what the “organic” label on Cuban honey really means—and the aftermath might not be as sweet as it tastes.

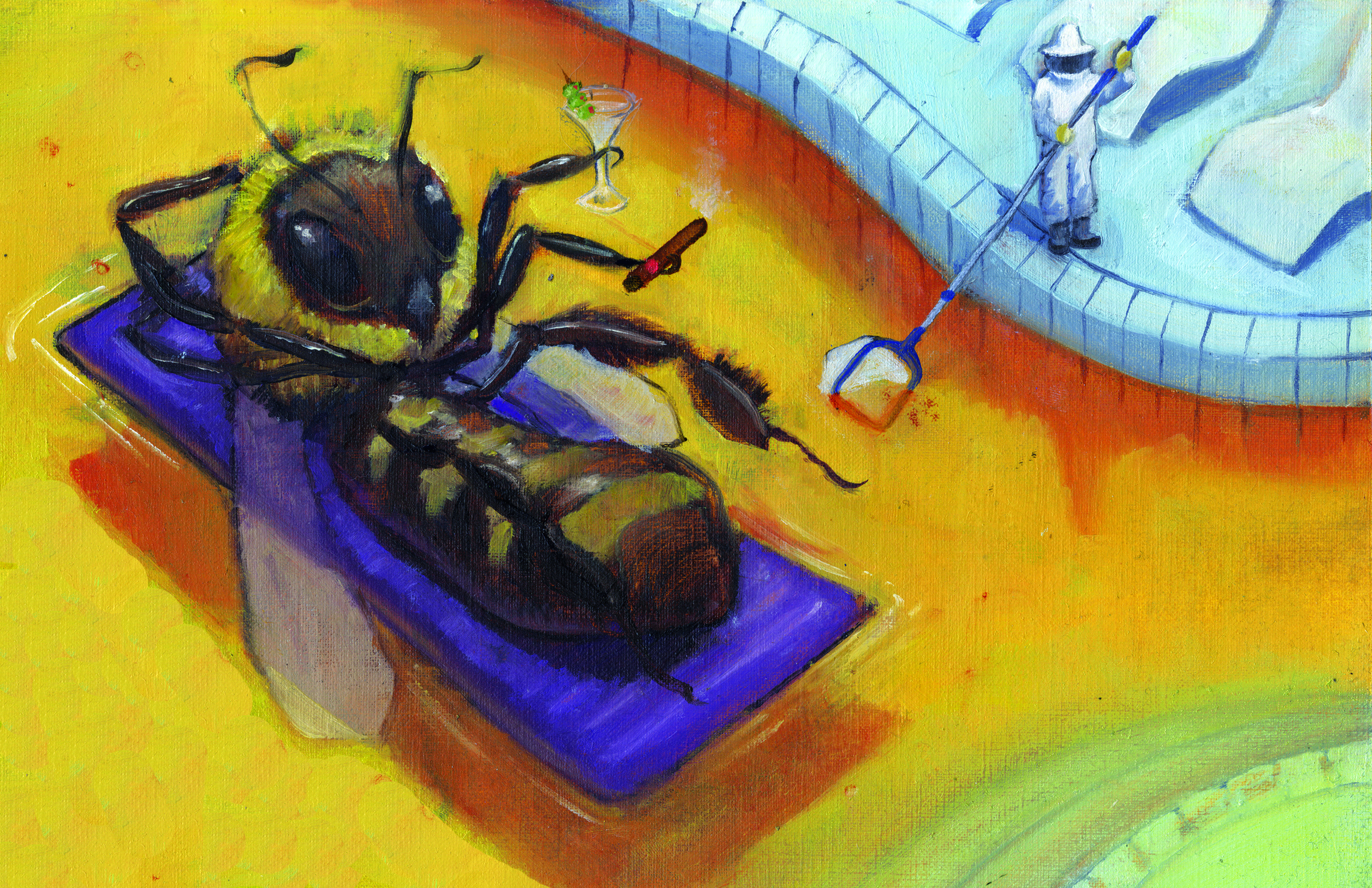

Illustration by Jonathan Muroya ’20: instagram.com/jonathan_muroya