Rates of homelessness in America have been increasing since 2016, reaching record highs in 2024. Despite declining unemployment rates post-pandemic, it has become increasingly difficult for Americans to find and maintain stable, affordable housing. From 2023 to 2024, “the number of people experiencing homelessness increased by 18 percent,” with a 39 percent increase in families with children experiencing homelessness. Combined with extreme temperatures and more frequent climate change-induced natural disasters, this increase in homelessness continues to place vulnerable populations at risk and must be addressed nationwide.

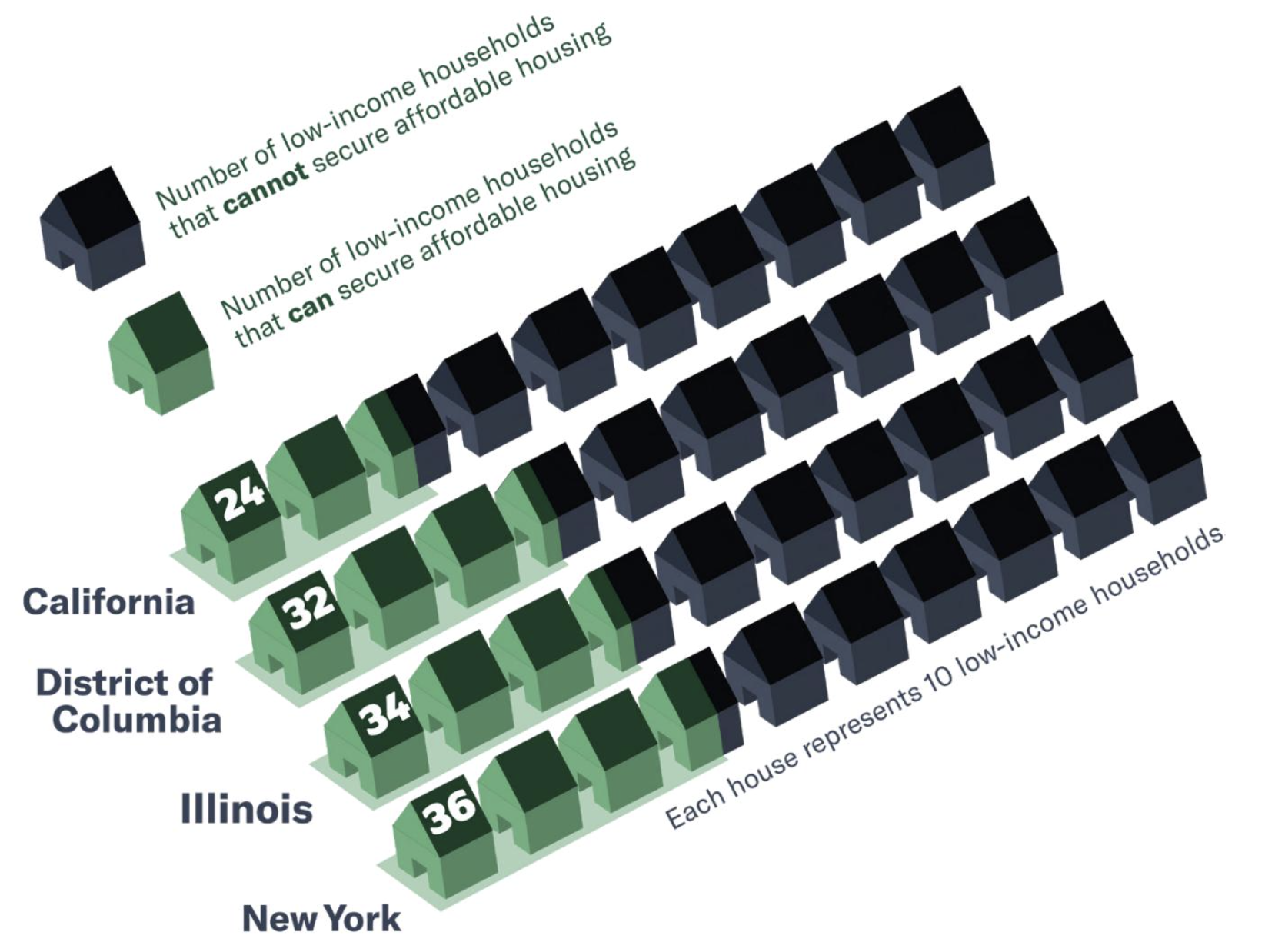

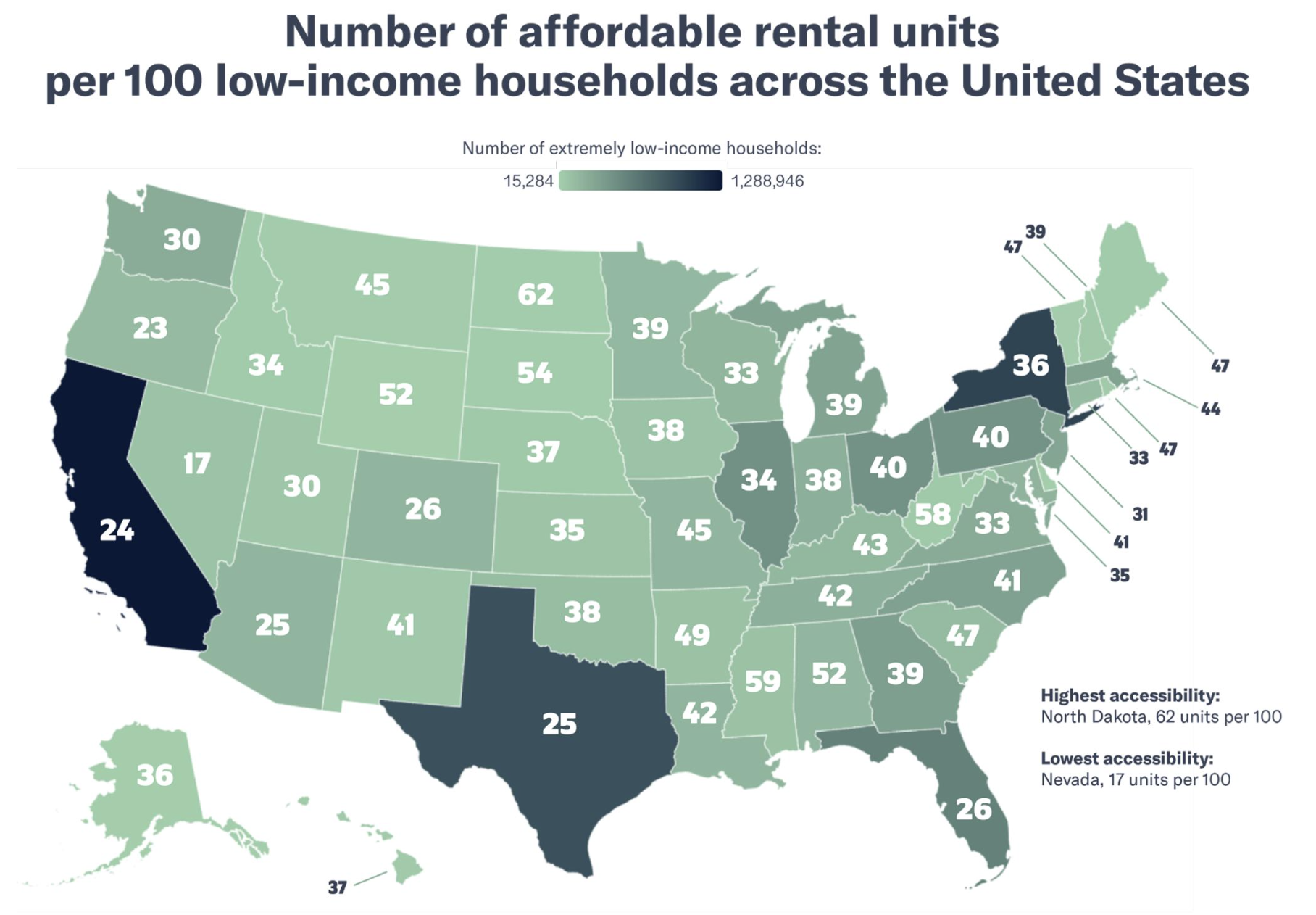

The main drivers of the current homelessness crisis in the United States are the high cost of living and the shortage of affordable housing in many cities. In 2023, over 49 percent of renters in the United States were considered rent-burdened, meaning they spent 30 percent or more of their household income on housing. For many low-income individuals, especially those living in high cost-of-living areas, this number can be higher than 30 percent, reaching unsustainable levels and leaving them without affordable housing. In New York, one of the most expensive states to live in, 74 percent of low-income renters are severely rent-burdened, or spend 50 percent or more of their household income on rent. Additionally, for every 100 extremely low-income renter households, there are only 36 affordable housing units available. Similar trends are seen across the United States, with only 24 available rental units per 100 extremely low-income households in California, 34 in Illinois, and 32 in Washington DC.

This shortage of affordable housing does not necessarily indicate a widespread lack of housing or a need for increased construction. While the lack of affordable housing contributes to the issue, the shortage is exacerbated by housing vacancies across the United States, especially in cities. Houses can be left vacant for months or years at a time, and in 2024, there were over 20 times as many vacant homes and apartments as unhoused people. Despite these vacancies, there is a severe lack of affordable housing, with only 35 “affordable and available” rentals existing for every 100 low-income households.

Cities facing homelessness crises often display not only a lack of units but also a mismanagement of affordable units. This problem is particularly acute in New York City, the most highly populated city and the city with the largest unhoused population in the country. In 2021, over 60,000 rent-stabilized homes in New York City were reported as vacant, yet the official vacancy rate reported by the US Census Bureau was much lower. In many cases, these homes have been kept off of the market by landlords to manufacture scarcity and raise rents, a practice known as “warehousing.” City officials have attempted to remedy this by passing Introduction 195, a bill that would make it much easier for city officials to gather accurate vacancy counts and hold landlords accountable. According to council officials, however, the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development still has not taken steps to implement the program, leaving landlords free to continue this practice. This issue is not unique to New York City: In 2023, the Chicago Housing Authority, an agency intended to provide affordable housing for those in need, kept 500 affordable housing units vacant and seemingly made no real attempt to fill them.

Countries that have effectively reduced homelessness have employed a “Housing First” approach, making housing available and affordable for unhoused individuals. As of 2023, only about 0.06 percent of Finland’s population was considered homeless, even including those temporarily living “with others in conventional housing.” This is a 35 percent decrease from 2008, when the Housing First approach was first adopted. In addition to building new housing units and allocating specific affordable units for currently unhoused individuals, Finnish officials at both the municipal and federal levels emphasized finding permanent housing for the unhoused as soon as possible.

While various local governments in the United States have attempted the Housing First approach, it has been unsuccessfully executed. For example, in New York City, former mayor Bill de Blasio introduced a plan to remedy the housing crisis by building 200,000 new units. Although he accomplished this goal, the housing crisis continued—many more units are needed, and similar issues persist with delisting. Current New York City Mayor Eric Adams has also proposed a plan to tackle the housing crisis by removing barriers for new construction, but this plan will take time to be implemented and it has not yet created real change. Unlike in Finland, these housing initiatives largely stop at construction or zoning, leaving the burden on the unhoused to find and fund housing—all while spending time in shelters. Additionally, while Finland provides additional support for the unhoused—such as mental health and employment services—New York City and many other cities in the United States primarily focus on housing units and leave the provision of services to NGOs. For American cities to solve the homelessness crisis, it is important to address the issue from multiple avenues. While construction incentives and increased housing are necessary, there is a significant supply of vacant housing that can be readily put to use to help unhoused people.

Some cities in the United States have attempted the Housing First strategy to reduce their large unhoused populations, but it must be adopted across the whole country with more determination to see real success. Additionally, a concerted and coordinated effort must be made to make better use of the available, yet vacant, housing that already exists. Government programs must not only create units but also focus on getting unhoused individuals and families into these existing units as soon as possible. To reduce the possibility of people becoming unhoused again, city officials should also prioritize permanent housing over temporary shelters and programs.