The BPR High School Program invites student writers to research, draft, and edit a college-level opinion article over the course of a semester. Lucien Gross is a senior at Kents Hill School in Maine.

Under Donald Trump, the Republican Party appears to have shifted away from its traditional policy stances. Trump has moved towards a more government-directed economic policy, demanding the state become a stakeholder in Intel and Nippon Steel and implementing a large-scale tariff system. At the same time, the president has befuddled observers by combining anti-intervention instincts of isolationists, such as opposition to NATO and a willingness to let Russia’s actions in Ukraine continue unimpeded, with harshly interventionist ideas, including potential territorial expansion into Canada or the Panama Canal. A recent anti-tariff ad from the Canadian government featured a speech by former Republican President Ronald Reagan, opposing the exact trade policies that Trump is implementing.

It has been said that Trump is forging a completely new, “populist” breed of conservatism. But that’s not quite right. Before the 1960s, conservatism wasn’t particularly pro-market or hawkish. It was only during the Cold War that Reagan and his political allies formed a coalition of social conservatives, economic libertarians, and foreign policy hawks. Now, under Trump, American conservatism may be reverting to its older form.

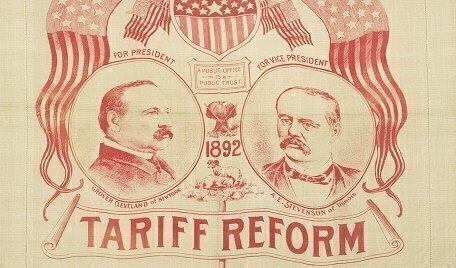

Trump has repeatedly praised William McKinley’s presidency, with its tariffs and imperial glories at the turn of the twentieth century, so it’s instructive to look back and see what was considered conservative in that time period. According to an 1899 paper by Nathan A. Smyth (then a law student at Yale), American conservatism had its origins in the Federalist Party led by Alexander Hamilton. In Smyth’s telling, pro-market, small-government movements were considered “radical” compared to economically interventionist “conservatives.” Such an ideological combination sounds strange today, but there are parallels between Hamiltonianism and Trumpism. Hamilton’s politics were broadly elitist and anti-democratic, but he also viewed himself as an opponent of laissez-faire economics, industrial policy, large-scale public works, and, indeed, excessive tariffs. This can help explain a seeming contradiction in Trumpian politics: Why would a movement that rejects free markets also pass tax cuts? The answer is that free markets may not be as automatically linked to support for the rich over the poor as is commonly assumed, considering Hamilton’s well-documented support for property requirements in voting. Free markets are inherently disruptive, forcing businesses to improve themselves if they wish to keep their consumers, which protectionism seeks to prevent.

On foreign policy, Trump seems to be merely following in the footsteps of the “sovereigntist” movement. The opposition by many conservatives to Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations plan for post-WWI peace was a good example of sovereigntist thinking: they were concerned that the League might force the United States into a war to defend some small country from an invader, or that the League might force them to give up their colonies in the Pacific and Caribbean. Sovereigntists were motivated by racial and religious concerns as well. They feared that international organizations, like the League and, later, the UN, would force an end to segregation and (based on a niche reading of the Book of Revelations) signal the arrival of the Antichrist. A sovereigntist would strongly oppose any organization binding the United States to war on behalf of other countries or in the name of democracy, while still supporting military action to expand American power and influence. Early 20th century conservatives also supported working with nations seen as sovereigntist, such as Rhodesia; a “whites only” UN was a serious proposal from this circle. All of this resonates strongly with Trump’s current foreign policy. His on-again off-again musings about military action against Venezuela are not driven by a desire to oust the dictatorial regime of Nicolas Maduro, but rather an example of nationalistic saber-rattling about drugs, and his aid to Argentina under Javier Milei shows a willingness to align with fellow conservatives.

Why did these forms of conservatism fade away? Really, the answer is the Soviet Union. Free-marketeers were naturally opposed to Soviet communism, social conservatives opposed its atheism, and Atlanticists (supporters of organizations such as NATO and of an aggressively pro-democracy foreign policy) saw the Soviets as the greatest threat to global democracy. During the 1950s and 1960s, under the influence of William F. Buckley and Barry Goldwater, the three groups formed a “fusionist,” neo-conservative ideology. But the Soviet Union has been gone for decades. It appears that the formerly marginalized factions are now returning to prominence.

Understanding Trumpism’s true ideological nature can help both parties refine their strategies in our new political era. Many internal disputes between GOP factions seem less irreconcilable within this framework: There isn’t necessarily a conflict between the business community and Hamiltonian dirigiste economics, and many disputes between “isolationists” and “interventionists” appear to be sovereigntists disagreeing on which nations should be considered fellow sovereignist conservative powers. For instance, in my opinion, the core of Marjorie Taylor Greene’s concern with Trump’s Israel policy may be that she doesn’t think a Jewish nation can count as one of these conservative powers. Democrats, meanwhile, should recognize that the free-market and Atlanticist factions are leaving the Republicans for good and fully bring them into their tent. They also should look at how opponents responded to this Hamiltonian type of conservatism in the past — for instance, Jackson combining attacks on the ultra-wealthy with attacks on the corruption inherent in a large government intervening in the economy, or Jefferson connecting John Adams’s opposition to aiding the French Revolutionaries with his anti-democratic actions domestically. Against Trump, this strategy of combining anti-authoritarianism, populism, and support for markets may be the best way to unite competing wings of the Democratic Party.