Source: 80 grados.

Creative Commons

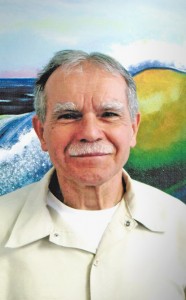

In a previous article, I wrote about the case of Puerto Rican political prisoner Oscar Lopez Rivera and the growing campaign in favor of his liberation. This week I take the opportunity to update readers on some of the campaign’s recent highlights.

Thanks to the actions of civil rights and Puerto Rican pro-independence organizations, word of Oscar Lopez Rivera continues to reach thousands of people both within and outside of Puerto Rico, even if the man himself is confined to the same federal prison he has lived in for years in Terre Haute, Indiana. The 70-year-old Puerto Rican independence activist is currently in his 32nd year of imprisonment. Following dozens of activities across the island and in the U.S., however, his case has grown more relevant than ever in Puerto Rican society. The many groups of the liberation campaign have kept up the pressure and recently gained some impressive victories as a result.

On September 11, the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL–CIO), the largest federation of unions in the U.S., approved a resolution demanding that President Barack Obama grant Lopez Rivera an executive pardon. On September 14, thousands of Puerto Ricans attended a concert honoring Lopez Rivera’s life and struggle. Some of the island’s most famous musicians participated, adding their voices to those of the many activists, politicians and other public figures that have lobbied for his release. And on September 16, Puerto Rican governor Alejandro Garcia Padilla brought the issue to light again during an official visit to Washington.

One of the more interesting events of the campaign, however, took place last month. On August 22, the Puerto Rican state department hosted a conference which brought together several professors and pro-Lopez Rivera activists to talk about the history of seditious conspiracy (the charge which Lopez Rivera was jailed for) and the similarities between the independence fighter and other famous political prisoners – specifically Nelson Mandela, former president of South Africa and leader of the armed struggle against the country’s apartheid system.

Predictably, many people call the comparison unfair and superficial. Detractors argue that Mandela’s actions enjoyed the support of a majority of his country’s population, while the Puerto Rican independence movement has never boasted a backing of the majority since the U.S. invaded the island in 1898. Others simply recoil at the notion of equating a world-renowned freedom fighter and politician to a man that is currently labeled as a domestic terrorist. These apparent differences do not address each man’s actions, but rather their historical context. When viewed in terms of individual actions and decisions, the similarities between Mandela and Lopez Rivera are much more apparent.

The most obvious resemblance is the prolonged imprisonment both men have endured for political reasons. Mandela, like Lopez Rivera, was charged with seditious conspiracy to overthrow his government and punished with a lengthy sentence. The man spent 27 years behind bars, enduring physical and psychological maltreatment. Lopez Rivera has spent 32 years in federal prisons on a 70-year sentence, suffering many of the same human rights abuses Mandela did, in addition to extended solitary confinement. Both men were vilified for using violent methods to aid their cause: Mandela for his covert bombing campaigns with the armed wing of the ANC (African National Congress), and Lopez Rivera for his participation in the pro-independence group FALN (Armed Forced for National Liberation). Due to their actions, both have been called extremists and terrorists.

Source: Wikipedia Commons. Creative Commons

Like so many other freedom fighters of the 20th century, Mandela and Lopez Rivera subscribed to leftist and liberationist ideologies typical of the Third World struggles of their times. Both experienced political and social marginalization due to their race and sought to aid their disempowered communities seeking greater representation – Mandela as a politician, Lopez Rivera as a community organizer.

Perhaps the most important similarities between both men are their strength of will and peace of mind in the face of adversity – their unconquerable souls. Mandela famously used his time in prison to keep fighting for his cause. The strength of his convictions was respected by fellow inmates, and his letters allowed him to shape events in South Africa and the rest of the world. Upon emerging from prison as an old man, his youthful energy and desire to better his country were undiminished. Over the course of the last 32 years, Lopez Rivera’s letters have strengthened the resolve of independence activists and sympathizers lobbying for his release. Through these letters he has helped shape the discourse of the contemporary Puerto Rican left wing, and made his case a rallying cry for many islanders. He showed his own strength when he declined a presidential pardon from Bill Clinton in solidarity with two fellow imprisoned independentistas who were not offered clemency.

El Nuevo Dia, Puerto Rico’s largest daily newspaper, recently agreed to publish Lopez Rivera’s periodic letters to his granddaughter. In one of these, titled “Where the Sea Breathes,” he writes about his experience in a supermax prison: “Did you know that ADX, the maximum security prison in Florence [CO], is filled with the US.’s worst criminals and is considered the most impregnable and harshest in the country? There, prisoners have no contact with each other. It is a labyrinth of steel and cement made to isolate and incapacitate. I was among the first to populate the prison” (my translation).

On June 30, President Obama visited Mandela’s old prison cell in Robben Island. Before leaving, he wrote the following message on the historical site’s guest book: “On behalf of our family we’re deeply humbled to stand where men of such courage faced down injustice and refused to yield. The world is grateful for the heroes of Robben Island, who remind us that no shackles or cells can match the strength of the human spirit.” It would be hard not to notice the irony of this statement. Those of us fighting for Oscar’s freedom hope that President Obama will soon recognize the Mandela in our midst, and make good on his many promises to respect expressions of Puerto Rican popular will. The bludgeon that is chance might have made Lopez Rivera a terrorist and Mandela a hero in America’s eyes, but the fates of men of such courage as them deserve not to be ignored.