Last week, Harvard Law School hosted a conference titled Reconsidering the Insular Cases, focusing on the controversial Supreme Court decisions (the eponymous “insular cases”) that determined the legality of the United States’ relationship with its non-state territories and that are largely still considered the basis for the Commonwealth between the U.S. and Puerto Rico.

The nature of the decisions reached during the Insular Cases has been the subject of much debate during the last century, but few expositions on the topic reflect the complex reality and incongruent results of their implementation in Puerto Rico’s case better than Juan R. Torruella’s panel presentation during this last conference. Torruella, judge in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First District — and the only Latino to have held that position — is an authoritative voice on how the application of these decisions, in his opinion tainted with the racial and ideological misconceptions of the American expansionist era, has negatively impacted Puerto Rico and all the American citizens born on the island.

Perhaps a bit of context is necessary before delving into normative statements. The Insular Cases were brought up in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, from which the United States emerged with several new overseas territories that, unlike previous land acquisitions, were not obtained with the purpose of being integrated into the Union. After the end of the war and the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1898, America had to answer some difficult questions about how best to manage control over these new jurisdictions.

The recent memory of the Civil War and Reconstruction led some to believe that the relationship between Americans and the peoples of these new territories would be based upon the newly established concept of political equality between racial groups on the mainland. However, these notions were thrown out the window in the wake of popular social Darwinism and the nationalistic mythos of Manifest Destiny. Under this ideological framework, American views of their new subject populations leaned towards the paternalistic and racist. Torruella cites the opinion of Simeon Baldwin, a Yale professor at the time of expansion, who stated that “[It would be unwise ] to give . . . . the ignorant and lawless brigands that infest Puerto Rico… the benefit[s] of [the Constitution].”

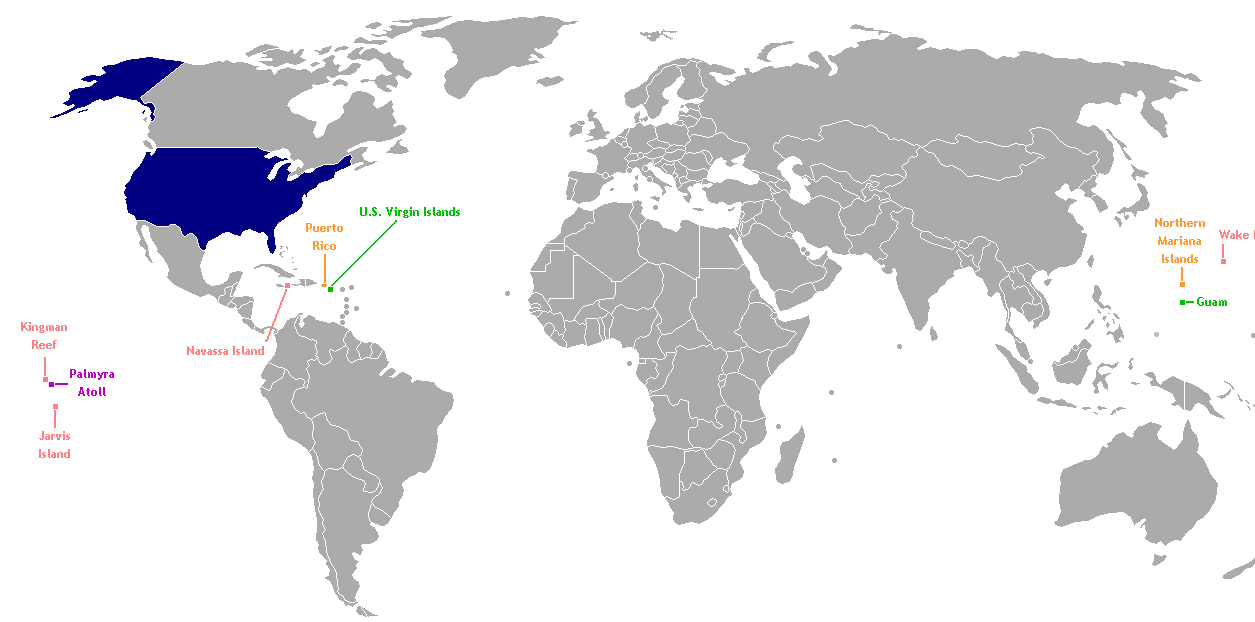

Thus, the Supreme Court developed a doctrine that responded to the ideological framework of the time, despite the Constitutional quandaries it gave rise to. Torruella mentions that the Insular Cases resulted in the creation of two territorial categories for areas under U.S. control: incorporated and non-incorporated territories. Everything obtained prior to the conflict with the Spanish was placed in under the former category, which generally reflected the intent to turn these acquisitions into states. All the gains of the Treaty of Paris, and the subsequent acquisition of the Virgin Islands, fell under the latter. Tellingly, none of these has been considered for admission into the Union. The Courts explicitly established the inferior status of these latest possessions by arguing that “the Constitution did not apply in full force to the unincorporated territories and instead, extended only a certain subset of rights deemed fundamental by the Court.” It would be hard to find better examples of modern imperialism.

Even though Puerto Ricans were granted U.S. citizenship (against their wishes) in 1917, the colonial relationship enshrined in the Insular Cases was maintained and reinforced. The Supreme Court decision for the 1922 Balzac v. Porto case argued that “locality was what determined which constitutional rights were bestowed upon individuals, not their individual status as citizens.” Therefore, the Puerto Ricans can only exercise their full rights as American citizens if residing in the mainland.

Like many Puerto Ricans, Judge Torruella subscribes to the view that the current U.S.-P.R. relationship is fundamentally a colonial one. He argues that the maintenance of this asymmetrical power relationship is made possible by the plenary powers — or as he calls the, “practically unfettered colonial powers” — that the Insular Cases grant Congress. Legislators get to decide the fate of non-incorporated U.S. territories, and since Puerto Rico has no congressmen or senators, those living on the island have no say in the political decisions taken for them. Torruella perceives this as subordination in the purest sense of the word and thus believes that the Commonwealth should not be called by any name other than a colony.

Continuing his diatribe against the Insular Cases, the judge cites an opinion expressed in Dred Scott v. Sandford on the nature of American control over non-incorporated territories from a constitutional perspective. The first of these opinions criticized the notion that the United States could even have colonies, since there is no mention of colonial relationships in the Constitution and thus no legal basis for it. The only authority given to the federal government in terms of gaining new territory is the admission of new states. By the views of the opinion’s author, Chief Justice Taney, the concept of non-incorporated territories was whipped up without regard to constitutional constraints. Needless to say, Torruella very much agrees.

Taking off his juror’s hat and putting on an activist cap, Torruella addresses this issue with what he calls “my Harvard Pronouncement.” Citing the recent referendum in which a majority of Puerto Ricans voted against the current Commonwealth status quo, the judge points out that the United States is left with the moral quandary of the “unassailable fact that what we have in the U.S.-P.R. relationship is government without the consent or participation of the governed.” Like so many of us Puerto Ricans, he perceives shakiness in our relationship with the United States, rooted as it is in legally and ideologically bankrupt foundations. The fact that these words come from a judge of the U.S. First District Court of Appeals is in no way surprising — prominent members of Puerto Rican and American society have been making similar arguments for generations. As Torruella himself points out, one of the few things that most Puerto Ricans can agree on is that the current Commonwealth does not alter the nature of our colonial status. Another thing most of us can agree on is that the recent referendum results won’t lead to any real attempts at change in Congress, since most of the island’s population is not in favor of immediate Puerto Rican independence and any attempts at making Puerto Rico a state would ruffle way too many feathers in Washington.

As it is unlikely that this will be resolved through traditional channels of political power (they have failed to alter the relationship for over 100 years), Torruella makes a rather unexpected call to “consider gradually engaging in time- honored civil rights actions, of which there are many successful examples,” primarily arguing in favor of measures of economic protest such as boycotting U.S. products. The sight of a senior federal judge calling for boycotts and civil disobedience by Puerto Ricans may have struck an odd chord in the halls of Harvard Law School, where so many of the policies that went into the Insular Cases were first formulated, but to those of us that have long been aware of Puerto Rico’s anti-democratic colonial situation, calls for direct and unorthodox action seem to be the only alternative left. Perhaps Judge Torruella’s pronouncements — and those of the other panelists — will help establish a new dialogue for change, and perhaps Puerto Rico might soon be presented with real alternatives to its current status. But I’d wager that most of us — including Judge Torruella — won’t be holding our breath.