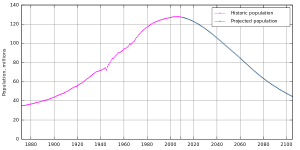

According to former Liberal Democratic Party minister Hakuo Yanagisawa, if Japan’s “baby making machines” stayed at home, they would produce more children and thus more workers. This economic justification for the fact only 60 percent of employable females participate in Japan’s labor force has proven feeble. By 2050, Japan’s working-age population is expected to fall by 40 percent, exerting a powerful drag on the Japanese economy. The dearth of women avoiding the labor force due to largely traditional, family-oriented reasons will significantly hamper the nation’s rapid economic progress.

Japan’s inability to maintain job equality thus far, defies the assumed synonymity between economic strength and geopolitical power and domestic human rights records. The World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Report ranked Japan 105th out of 136 nations in 2013 for gender inequality and 120th in terms of women in parliament. Women comprise of a mere 2 percent of Japanese business directors, while the OECD reported that in the business sphere, the median salary of a working Japanese mother is 61 percent lower than that of a man in an equivalent situation. Although this begs the question of whether the two situations can be feasibly equated, according to Georges Desvaux, the head of McKinsey’s Tokyo office, foreign companies have been able to take advantage of this prejudice by hiring and promoting female employers, thus capitalizing on the fact that Japan is not harnessing its own potential (Japan consistently ranks within the top twenty in education league-tables compiled by the OECD).

According to Professor Laura Tyson, professor at the Haas School of Business and ex-chairwoman of the Council of Economic Advisors under President Clinton, “among economists (most of whom are male), there is a tendency to treat diversity and gender issues as ‘soft’ issues, secondary to the real business of growth, job creation and productivity.” Higher deficit spending and a vast quantitative easing program by the Bank of Japan have caused the Japanese economy to grow at 4 percent, the highest rate amongst developed economies. To maintain rapid growth, however, Japan must adopt social policies that complement and enhance its economic progress. The imbalance caused by gender discrimination has jumped to the top of the agenda as Prime Minister Shinzo Abe works to shake Japan out of its 20-year deflationary slump.

Under his policy of “Abenomics,” discussed by BPR’s Carter Johnson in The Anniversary of Abenomics, Prime Minister Abe has declared his desire to let women “shine” in the economy. Goldman Sachs has reported that raising female labor participation would add 8 million people to Japan’s shrinking workforce and raise GDP by 15 percent. Despite the evident economic benefits, Japan’s gender disparity is underscored by deeply rooted traditional values that have been routinely reinforced by supporting social structures. In 2005, before his recent change of opinion, even Prime Minister Abe warned of the damage to family values and to Japanese culture that could result if men and women were treated equally in terms of employment.

Although Abe’s interest is new; the problem is not. Yoko Kamikawa, Prime Minister Abe’s minister of gender equality during the 2001, states she is startled by the lack of progress thus far. The underlying issue behind the gender disparity lies in unwillingness on behalf of large companies and conglomerates to hire women who will inevitably take maternity leave and hinder productivity. While married mothers are largely absent from the workforce, returning women can only obtain part-time or temporary jobs with low pay and minimal security. According to the OECD, Japanese women earn about 72 percent of the compensation of men for equivalent jobs and this gap rises during childbearing indicating a type of “motherhood pay penalty,” as inferred by Professor Tyson.

Those who do stay in their jobs regardless of maternal obligations often waste their abilities. Despite the high level of women’s education in Japan, only a few women hold professional, technical or managerial positions. In 2012, women accounted for 77 percent of Japan’s part-time and temporary workforce. However, Japan’s “bamboo-ceiling,” – referred to as such for being “thick, hard and not even transparent” has showed its first signs of disintegration. In 2011, 4.5 percent of company division heads were females, compared to 1989’s 1.2 percent. Only a mere 1 percent, however, held the most senior executive level positions. The equivalent figures in China and Singapore are 9 percent and 15 percent, respectively.

According to Sakie Fukushima, a director of Keizai Doyukai, human-resources executives say in private that they would hire young women ahead of men most of the time but are afraid of losing them due to children. It is this very trend in corporate culture, through which companies hire recent graduates for life-long professions, that prevents temporary breaks in employment. Prime Minister Abe has proposed increased day care opportunities to mitigate this issue, though many Japanese women distrust the day care system.

Abe has also suggested expanding childcare leave to three years instead of the 18 months allowed under the existing law, yet most women do not even use the 18 months in fear of losing their jobs. The policy can also be viewed as an attempt in line with the old agenda of keeping women at home. Critics are also displeased by the fact that Abe’s policy does not endorse paternity leave, further reinforcing a woman’s role as the primary child-bearer. In January, the World Economic Forum suggested hiring foreign nannies to care of children, yet Japan’s current immigration rules do not make to such a solution likely. A Japanese woman cannot receive a visa for a foreign nanny, but a Japanese nightclub owner can receive one for a foreign female entertainer.

Recently, however, Abe has proposed allowing as many as 200,000 foreigners per year to work in areas such as construction, childcare and nursing. As with much of Abe’s structurally ambitious “Abenomics,” such a loosening may prove political unfeasible due to the unpopularity of immigration within Japan’s insular borders. Abe’s sudden economic changes can also be perceived as a threat to traditional Japanese values by both industries and the general public. The “pampered woman” syndrome prevalent in many Asian countries and discussed in author Mariko Bando’s guide “The Dignity of a Woman,” indicates that Japanese women did not feel they needed a high-status job to enjoy high-status. Only a high-status marriage was deemed necessary. In 1979, 70 percent of Japanese women agreed that the man should be the breadwinner and the wife should “take care of the home.” By 2012, post-recession and due an increasing need to work, only half said they preferred to stay at home.

The fear of the labor force decreasing 40 percent by 2050, spurred by the detrimental effect Japan’s backward social policies are having on the nation’s economy, has fostered common ground between Japanese traditionalists and progressives. Although Prime Minister Abe faces an uphill battle in tackling corporate practices that undermine women’s opportunities and subsequently Japan’s economy, his decision to enact legislation promoting the role of women in the labor force and his recognition that women are “Japan’s most underutilized resource” are critical first steps. A fundamental reason to believe Abe’s policies may succeed is that there is no alternative, especially in the face of a rapidly aging national population.

A timely article–definitely an issue that Japan will have to spend years addressing. It’s no easier than the crumbling general wages in the US, or a problem we Taiwanese have: relying on a immigrant underclass to take care of children or the elderly. Hopefully the WEF realizes that creating a poorly treated immigrant underclass that is unfairly compensated and paid is not a meaningful solution for Japan’s systemic troubles, no matter how attractive and widespread a Band-Aid it is. The real solution will be reform of workplace legislation, the social safety net, and changing values. I wish we in Taiwan would learn that, instead of expecting poorly paid expats to fix all of our problems.