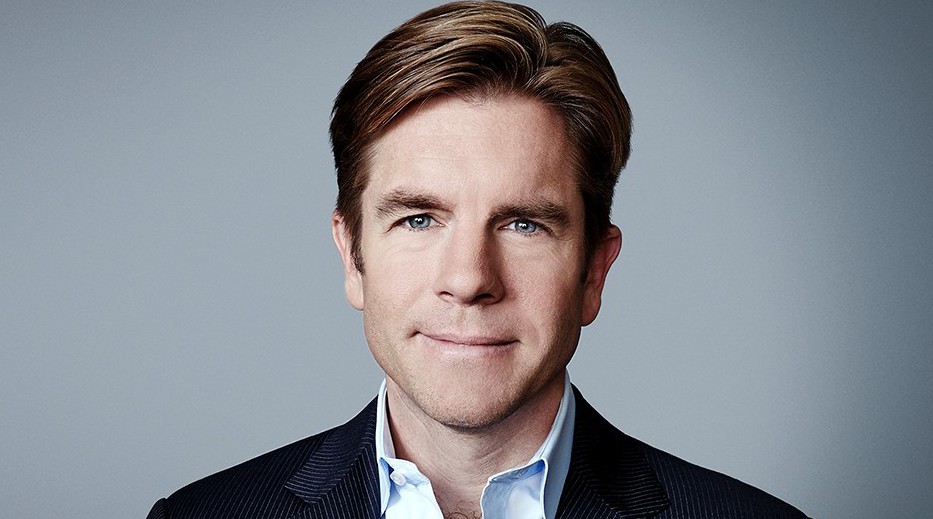

Ivan Watson ‘97 is the senior foreign correspondent for CNN in Hong Kong. He has reported on a broad scope of major global events, including the Haitian Earthquake and the recent Ukrainian crisis.

Brown Political Review: How do you maintain objectivity when reporting on travesties?

Ivan Watson: My primary responsibility is to deliver facts about what is going on and to try to do it as fairly as possible, but if you are witnessing an overt act of evil, there is no way to argue what is happening there. You call it what it is. That is not a case of these people claim one thing and these people argue another; we have an incredible phenomenon taking place in front of our eyes, and it’s not debatable. A lot of other reporting isn’t as black and white. You try to show both sides of the story and make sure that your facts are well sourced before you go to air with them.

BPR: What have you learned about war? What has surprised you?

IW: War is pretty awful. There will be a lot of shooting, but it doesn’t seem to be hitting or hurting the combatants…it’s always ordinary civilian people and usually the ones with the worst economic situation who are hit the hardest…That’s one of the rules of conflict that I’ve picked up. It’s really a lot easier to destroy something than to build something. A year ago there wasn’t a war in Eastern Ukraine…I did not see enmity between ethnic Russians and ethnic Ukrainians. They got along. But a narrative was created that said that Ukranians were Fascists and thugs and Nazis and that they were oppressing Russians, and it was promoted. Now there is real hatred between two ethnic people who live side-by-side, intermingled linguistically and in a familial way, and that’s really an awful thing to witness.

BPR: How has your experience reporting in Ukraine helped you understand the causes of the conflict?

IW: It’s incredible how political leaders can manipulate something that feels like a small difference and turn it into something that is much bigger. Control of the media is one of the most basic ways to do that. That’s a big part of the equation of what happened in Ukraine. It was a country that had problems, but it worked. Now there’s a separatist movement and mutual enmity. It’s incredible to me how fast that happened.

BPR: Can you compare the role you’ve had, from freelance journalism to NPR and then to CNN?

IW: Going from radio to television meant having a much smaller footprint. In television, if you show up in a village in the middle of nowhere, it’s a big event. People also react differently to cameras and lenses than they do to somebody with a notebook, or somebody with a little microphone — they can get aggressive. When I was a radio reporter, I was a dorky guy sitting with a shotgun microphone recording the sounds of a babbling brook to help enrich the story with some texture. In television, you need to be right upfront with the action, and when there’s trouble you need to be charging into the action rather than just observing from a safe distance.

BPR: You’ve been harassed live on air: In Ukraine you were accosted by people holding weapons, and in Turkey, you were asked, “What are your credentials?” How do you respond to this type of aggressive situation?

IW: In the case in Istanbul, I was broadcasting live. I tried to respectfully deal with the police, who accused me of not having credentials, and with the live international audience as best as I could. I don’t know if I handled it well or not. I told the Turkish police afterwards: “You know, this is live.” When you are around a large number of people with guns in a conflict zone, there aren’t a lot of rules. You could have planned and spoken and gotten permits from commanders, and all it takes is one psycho and his buddy to spoil it. That’s what happened when we were near a separatist checkpoint outside Donestk in Eastern Ukraine, where we had permission to interview the fighters. Two guys showed up and the next thing you know they were cocking their guns at us and lining me and my team up on our knees on the side of the road and threatening to shoot us. In that case, I talked them down. It was the one time in my career that I used my Russian Orthodox Christian background. What happened was that a couple of guys showed up and accused us, as Americans on CNN, of being liars, and they warned people not to trust anything we did. The guy who I interviewed had given this very passionate statement saying, in Russian, “My friends, we didn’t [kill civilians], we didn’t do it.” He was clearly very motivated by his faith, and after he got riled up he said, “If you lie about what we talked about, I’m going to kill you.” I said, “Listen, brother, I’m Russian Orthodox just like you. I would never do that, you’ve got to trust me.” It’s the one time in my career that being a little boy named Ivan and being an alter boy helped. It was a fortunate resolution to a dicey situation.

BPR: Despite the things that you have seen in your career, you have said that most of the world is not evil. Can you describe what you mean by that?

IW: As much time as we journalists spend reporting on the crises around the world, whether they are economic or political, we occasionally get to report on beautiful and very human things as well. I am dismayed sometimes when I come back home and I get the impression that people think that the outside world is this terrible, scary place. It’s not. It’s rich, and it’s beautiful, and it’s amazing. That’s part of why I went overseas after [graduating from] Brown, and it’s why I’ve basically stayed overseas since 1998. As an adult, I’ve lived longer overseas than I have in America. I do that not because of the crises and the troubles, but because it is an incredible experience. You’re learning and doing something new everyday. That sounds a little bit like college to me.