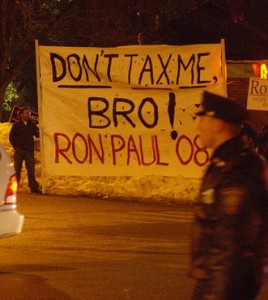

A strikingly common cornerstone of right-libertarianism (and, correspondingly, the modern American libertarian movement) is the assertion that “taxes are immoral.” This argument can take a number of forms, some significantly stronger than others. I wish to address two of the formulations of this argument that have appeared in recent articles in different publications on the Brown campus and from this, hopefully eke out what a sounder formulation of this argument would entail.

A strikingly common cornerstone of right-libertarianism (and, correspondingly, the modern American libertarian movement) is the assertion that “taxes are immoral.” This argument can take a number of forms, some significantly stronger than others. I wish to address two of the formulations of this argument that have appeared in recent articles in different publications on the Brown campus and from this, hopefully eke out what a sounder formulation of this argument would entail.

A weak form of this argument appears in Oliver Hudson’s article for the Brown Daily Herald, “Universal Suffrage is Immoral.” It appears not explicitly but in the course of his larger argument which I have no interest in even beginning to refute here. The crux of the argument is that taxes are roughly morally equivalent to theft.

Hudson tries to make this sort of argument by appealing to a common moral intuition, stating: “most would agree that controlling how your neighbor or friend spends his or her money is morally wrong.” This assertion is uncontroversial. However, the assertion that follows is less so. Hudson continues: “if you went to your friend and told him you’re taking his money to donate to charitable causes “for the good of the public” that would be fine? It is noteworthy that we call one case stealing and the other taxation, but they are effectively the same.” A parallel argument would run something like this: “if you caught someone forging a check of a value greater than $500 and imprisoned him in a room in your house for four years that would be fine? It is noteworthy that we call one case illegal kidnapping and the other justified punishment, but they are effectively the same.”

It is not exactly noteworthy that there are actions that a government can take that we would definitely not allow any individual citizen to commit. This could be for a number of reasons, but the primary idea seems to revolve around the fact that there is a robust system of checks and balances that limit when a government can and cannot do something like the removal of funds from a person or restricting their freedoms through imprisonment. This robust system of checks and balances, at least theoretically, means that any action taken on the part of the government must have a much stronger underlying rationalization than the actions taken by any individual. Allowing any given individual to remove funds for the common good or imprison another individual for violation of the common good under his own judgment gives us no guarantee that his judgment will be sound, nor that the common good will be served via the extraction of those funds or that person’s imprisonment. Of course, there is the possibility that any particular instantiation of self-limiting functions of government might be flawed, but it does not follow from this that all conceivable functions of government are flawed likewise.

A stronger version of this argument which appears in Benjamin Koatz’s article “His Holiness and State Sponsored Violence” runs like this: “Taxes are involuntary. If you don’t pay your taxes you go to jail. Police steal you away and put you in a cell, by force. Meaning, that government programs are funded at the point of a? [sic] Gun.” In context, the argument fixes around the Dalai Lama’s rejection of violence and I think, for the sake of fairness, a similarly complete rejection of violence as a means should probably be assumed. To be honest, I am unsure what the Dalai Lama’s stance on the use of violence in self-defense or to defend others is, however, I would think that most people without a radical religious or philosophical stance would probably agree that there are certain limited cases where violence is permissible.

Even if we concede that violence is never justified it does not necessarily follow that use of force is never justified as it is not exactly clear that all force is violence. The most salient illustration of the issue is a parent walking next to a busy street with a child. The child, excited by something on the other side of the road, runs into the street and his parent grabs him by the arm to pull him back. This is certainly a use of force as the parent grabs the child’s arm and physically moves him back onto the pavement, but only an incredibly loose definition of violence would include this act. Furthermore, any definition of violence which includes this act would seriously cast doubt on the idea of all violence being morally wrong as this action hardly seems to be wrong. This particular example seems to illustrate that there are certain situations where the use of force is justified in order to prevent harm from befalling someone.

Even if we concede that violence is never justified it does not necessarily follow that use of force is never justified as it is not exactly clear that all force is violence. The most salient illustration of the issue is a parent walking next to a busy street with a child. The child, excited by something on the other side of the road, runs into the street and his parent grabs him by the arm to pull him back. This is certainly a use of force as the parent grabs the child’s arm and physically moves him back onto the pavement, but only an incredibly loose definition of violence would include this act. Furthermore, any definition of violence which includes this act would seriously cast doubt on the idea of all violence being morally wrong as this action hardly seems to be wrong. This particular example seems to illustrate that there are certain situations where the use of force is justified in order to prevent harm from befalling someone.

In conjunction with this previous point, it seems notable that we generally consider people to have a moral obligation not just to refrain from doing harm to others, but also to prevent harm from befalling others if the cost to them is negligible. For example, if an able-bodied individual was to come across a quadriplegic who had fallen into a shallow body of water and was now drowning for lack of ability to remove themselves and the able-bodied individual could prevent the death of the quadriplegic at the cost of merely getting his sleeves wet, not helping said quadriplegic would be morally wrong. If this is the case and we accept that force is sometimes justified to prevent harm from befalling an individual as illustrated above, then it does not seem that one would be incredibly remiss to create a statute, which, by force of imprisonment or fine, would obligate able-bodied people to help mitigate possible harm to others whenever the cost to them would be negligible. How the argument follows from here should be relatively clear. People with large amounts of money can, without question, sacrifice an amount of their holdings with no noticeable effect to their quality of life nor to their physical person while this same negligible sacrifice could literally prevent people from dying whether it be from starvation or preventable illness.

The objection to this point runs something like this: yes, this is all well and good, but that money is the rich person’s property. How can we ever justify violating his right to his own property? The problem with this objection is that it automatically glosses over an entire (quite interesting) issue: what does it exactly mean to say that something is someone’s property? Or, more specifically, what relationship must one have to something to say that they have an inalienable right to the possession of something?

The Lockean model of property ownership as an extension of the right to personal sovereignty in the form of labor is a compelling one and is generally, I think, the one that runs implicitly in most discussions of property. If we own our labor, why should we not own the products of our labor as well? But as Locke recognized, this model cannot hold in the face of scarcity. The right to property is not the sole existing right, we recognize, at the very least, a right to life as well. And, in most cases, this right is far more fundamental (and far less controversial) than the right to property. Consider a group of people traveling through a desert, the strongest and fastest comes upon a fruit tree and picks all of the fruit for himself, he has technically mixed his labor with the fruit, but to assert that he has an absolute right to dispense with the food as he will is to say that his right to property is more important than the other individuals’ right to life. I cannot think of a way to justify this conclusion, and to do so requires an incredibly strong argument as it flies so intensely in the face of our moral intuitions. On the other hand, if there was exactly enough food for one individual to survive, there would be a strong moral argument for the fastest to keep the fruit of the tree. However, this does not stem from his right to property qua property but instead to his right to property insofar as it enables him to continue living. He does not have an obligation to give up goods that he needs to survive in order that others might, but he does not have a right to stockpile food if others might die.

The Lockean model of property ownership as an extension of the right to personal sovereignty in the form of labor is a compelling one and is generally, I think, the one that runs implicitly in most discussions of property. If we own our labor, why should we not own the products of our labor as well? But as Locke recognized, this model cannot hold in the face of scarcity. The right to property is not the sole existing right, we recognize, at the very least, a right to life as well. And, in most cases, this right is far more fundamental (and far less controversial) than the right to property. Consider a group of people traveling through a desert, the strongest and fastest comes upon a fruit tree and picks all of the fruit for himself, he has technically mixed his labor with the fruit, but to assert that he has an absolute right to dispense with the food as he will is to say that his right to property is more important than the other individuals’ right to life. I cannot think of a way to justify this conclusion, and to do so requires an incredibly strong argument as it flies so intensely in the face of our moral intuitions. On the other hand, if there was exactly enough food for one individual to survive, there would be a strong moral argument for the fastest to keep the fruit of the tree. However, this does not stem from his right to property qua property but instead to his right to property insofar as it enables him to continue living. He does not have an obligation to give up goods that he needs to survive in order that others might, but he does not have a right to stockpile food if others might die.

And this is the question that staunch tax opponents must answer: what could possibly give an individual the right to stockpile goods above and beyond his personal needs when there are others suffering for lack of them? A mere appeal to the right to property is not enough, as the right to life is generally considered the most fundamental. The government exists for many reasons, but the most primary is to protect the interests of those it governs. It is definitely in the interests of the poorest among us to not starve or die from preventable illness and when the cost to stop these things is so small as to be literally unnoticeable for the richest among us, there must be an incredibly strong ontological justification for the existence of a property right stronger than the right to life.

And this is the question that staunch tax opponents must answer: what could possibly give an individual the right to stockpile goods above and beyond his personal needs when there are others suffering for lack of them? A mere appeal to the right to property is not enough, as the right to life is generally considered the most fundamental. The government exists for many reasons, but the most primary is to protect the interests of those it governs. It is definitely in the interests of the poorest among us to not starve or die from preventable illness and when the cost to stop these things is so small as to be literally unnoticeable for the richest among us, there must be an incredibly strong ontological justification for the existence of a property right stronger than the right to life.

All the preceding arguments are not meant to illustrate that taxes are a distinctly moral institution. And it should go without saying that taxes not being a moral institution does not mean that they are an immoral one. There are many things which exist which are outside the scope of morality entirely (e.g. traffic laws). These sorts of things merely exist out of organizational efficiency, i.e. we get better outcomes from having traffic laws (or, possibly, taxes) than if we do not. In order to deduce the conclusion that taxes are positively immoral there are some underlying claims which must be put forth quite strongly. These claims are: first, a moral theory that asserts that all uses of force (except, possibly, to prevent another use of force) are immoral. Second, a theory of government which can exist while utilizing exactly zero force (except, again, possibly to prevent another use of force.) And finally, a theory of property rights so robust that it can: a) justify the accumulation of property far beyond what one human being could use, b) establishes said rights as more sacrosanct than the right to life in order to establish c) the right to dispose of that surplus property however one wishes even if people starving and dying as a consequence and d) exist without recourse to any form of codified force used by the government or justify the use of force to protect property (possibly by establishing theft as a use of force).

This is no small task, but claims of immorality (or morality) are large claims. I do not think that I could construct anything resembling such as system under any existing moral theory, but perhaps that says more about my cognitive abilities than the difficulty of the argument. Regardless, if anyone feels up to attempting this herculean task, good luck.

As more copulation and innovation of more life forms as babies produced at this time the inevitable outcome of this right is a impact upon my existence and a compromise leading to a deterioration of the human condition and that of the planet a fate few would deny.

“And it should go without saying that taxes not being a moral institution does not mean that they are an immoral one. There are many things which exist which are outside the scope of morality entirely (e.g. traffic laws). These sorts of things merely exist out of organizational efficiency, i.e. we get better outcomes from having traffic laws (or, possibly, taxes) than if we do not.”

http://www.bikewalk.org/pdfs/trafficcontrol_backt…

I think "heckledoncampus" pretty much said everything I would've said, but here's all the points summed up, many of which are just reiterations of what I said in my article and you seemingly chose to ignore:

I said that not all taxation is bad, and you parenthetically acknowledged my point that taxation to prevent force is desirable in your second-to-last paragraph. But what I was solely advocating in my article was the acknowledgement that taxation is founded in violent force, and a subsequent hesitancy to use it to solve all our problems.

This brings me to my second point: the government can't/hasn't been proven to be able to solve all our problems. The issues of poverty, hunger, and 'right to life' or even a better livelihood are all fundamental problems that have existed throughout human existence, and in fact, I believe, like "heckled" does, that the facts show that respect for property rights, limited government, and less taxation solve them far better than any government program or bureau could. Your thinking that taxation is justified in the case of providing someone's 'right to life', is founded in the if not incorrect then at least debatable conclusion that the government provides that right better than the market or voluntary trade can. It's a debate for another article, but I hope you at least realize that if you come to the utilitarian libertarian (utilibertarian) conclusion that free markets/voluntary charity are better for the poor than government welfare is, that your main 'right to life' reasoning for taxation is kind of moot.

Also, the government is not our parent, we are not its child, and protecting us from our own actions and mistakes (even running into the street) would not be justified from any libertarian standpoint.

Finally, I do completely support someone's right to horde wealth to any extreme. The fundamental good about capitalism though, is that there isn't just a communal pile of goods from which a greedy rich person can steal and deprive others of those goods. The ONLY way, in a free market where fraud and force are protected against, that a rich person can acquire any amount of wealth, is by providing the best product at the lowest cost to the most people. E.g., improving the lives and livelihoods of those you are so concerned about throughout your article. I'm okay with Whole Food's/Target's/BJ's CEO being rich because they are getting that money from providing a much needed service to a bunch of people at a lower cost.

Finally, thanks for the neo-liberal tag. Though I guess it's technically correct, it's also just what libertarians need, to be connected with those other famous 'neo-liberals' like George W., Cheney and Rumsfeld… 🙂

Well done, Luke. You do a great job of refuting the garden-variety "it's my money, you can't take it" libertarian argument against taxes, while leaving open the door for principled libertarians who genuinely believe that the government's only purview is preventing citizens from harming one another.

I understand that about 60% of budget expenditures go towards entitlements, I am not denying that, I am saying that only a fraction of those receiving entitlements actually legitimately could not go without them, therefore the moral parameters only encompass those very few, and those very few would be better served by private charity anyway. "Ever since 1996, welfare and COBRA payments have reliably operated on a contingency of its recipients searching for work" yes, and in that time the amount of people receiving cash handouts has decreased, thankfully, but it hasn't done much good because the number of people receiving non-cash handouts in that same time frame increased proportionally.

To “HeckledOnCampus”: I empathize with your frustration about how certain arguments could be fallaciously extrapolated to encompass all libertarianism, but I think **you* are straw-manning Dowling. The fact remains that this author hasn’t undertaken to deconstruct all the various facets of libertarian thought–that’s an odysseys that requires volumes. He’s responding to two relatively commonplace strains of reasoning that were recently deployed by two high-profile libertarians on campus, no less. Speaking of straw-manning:

“Your argument protects enormous steps toward expanding government influence by wrapping it in the emotional argument of “what about the poor and sick”, who are only a fraction of those who receive more money from the government than they pay in. It is the equivalent of using slogans like “support the troops” to put illegal wars beyond criticism.”

Well, in fact about 60% of budget expenditures finance entitlements, namely Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. So, more or less, the vast majority of “free” handouts reside within the author’s distinctly moral parameters. The handouts that don’t, tellingly, often don’t really constitute “handouts.” Ever since 1996, welfare and COBRA payments have reliably operated on a contingency of its recipients searching for work. Just some things to think about.

Excellent, excellent analysis. I learned a lot.

Focusing on the taxes as violence debate attempts to straw-man the libertarian position. You’re article paints the libertarian party as composed entirely of near anarchist, anti-statists who will accept nothing short of absolutely zero taxation. Many, if not most, libertarians though, are more minarchists or even classical liberals who often times voice their support for a market free from government interference based on the empirical evidence for the success of such a society, not necessarily on the individual rights of man. You have selected a single philosophical foundation (Lockean model), adopted by some libertarians, to represent them all. You have not directly faced the utilitarian, or more accurately, consequentialist metaphysics that many libertarians found their beliefs in, which point to the historical fact that maximum health, wealth, and freedom, for all people, is most often established in societies with minimal restrictions on property and trade, and that as such societies become more socialist (bigger government) by to establishing larger defense and related industries (Wars, foreign bases, CIA, DIA etc…) and providing ever increasing “free” handouts (Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, etc…) they inevitably bankrupt themselves and infantilize their population without improving care to the needy.

“the primary idea seems to revolve around the fact that there is a robust system of checks and balances that limit when a government can and cannot do something like the removal of funds from a person or restricting their freedoms through imprisonment. This robust system of checks and balances, at least theoretically, means that any action taken on the part of the government must have a much stronger underlying rationalization than the actions taken by any individual. Allowing any given individual to remove funds for the common good or imprison another individual for violation of the common good under his own judgment gives us no guarantee that his judgment will be sound, nor that the common good will be served via the extraction of those funds or that person’s imprisonment. Of course, there is the possibility that any particular instantiation of self-limiting functions of government might be flawed, but it does not follow from this that all conceivable functions of government are flawed likewise.”

Most libertarians are not anarchists and do concede the right to force (military, police, courts etc…) and limited taxation to the government, but this is not to say that direct taxation without a direct benefit, such as the income tax, should be used to fund such pursuits (which grow far out of hand when given such massive funds). The system of checks and balances was established by classical liberals who sought to minimize government interference partly by setting the different branches of government at odds with one another so that no given part, and by extension the whole, could grow too powerful. Of course such a system can be trusted with minimal force and limited taxation powers where an unchecked individual should not be, but Libertarians do not advocate for the abolishment of such a system or the extension of such rights to harm others to individuals. The Libertarian position is that individuals should have the freedom to do what they please so long as they do not harm others, and that the government should step in only to prevent such harm. It is the corruption of this system and the unconstitutional concentration of power in the hands of the executive branch that has begun to ruin the individualism of Americans and persuade them to trust that the government is meant to serve some function other than the maintenance of peace, order and just law courts.

Libertarians object to most taxes as immoral on the grounds that they are taken arbitrarily and without direct recompense to the payer. Libertarians generally concede to the government sources of revenue such as flat rate sales taxes, contract fees, bond selling, excise taxes, and property taxes used to fund the government services, like the police, for the region in which the property is located. Such taxes should more than cover the constitutionally permitted actions of the national government and would only tax in proportion to one’s participation in certain activities and purchase of goods. They would not even come close to funding massive expenditure on corporate bailouts, foreign wars, and welfare for those who do not need it. Libertarians seek minimal taxation partly because it necessarily entails minimal government, which in turn results in an imperfect but historically wealthier and healthier society than one of government control. You bemoan the fate of the poor in a society with little taxation, but the poor are not aided by the destruction of wealth and jobs facilitated by crippling government interference in the economy.

“The government exists for many reasons, but the most primary is to protect the interests of those it governs. It is definitely in the interests of the poorest among us to not starve or die from preventable illness and when the cost to stop these things is so small as to be literally unnoticeable for the richest among us, there must be an incredibly strong ontological justification for the existence of a property right stronger than the right to life.”

But those taxes are often used against the interests of those it governs, to spy on them, to establish military bases around the world, to invade foreign countries, to further inflate already bloated government bureaucracies, and to provide services less efficiently, less quickly and at a higher cost than private enterprise. It is also not the case that “the richest among us” are capable of providing sustenance for the poor and needy of the nation entirely in and of themselves, and it would certainly not be an unnoticeable expense. If you were to tax the $250k+ a year income tax bracket %100 of their income you would still not be able to fund the entirety of the government, and most of that revenue would still have to come from the other brackets, or, better yet, from cutting spending. The primary use of taxes currently is far removed from preventing the most unfortunate from starvation and succumbing to illness, and a great many more recipients of government handouts were not near the brink of starvation when taken under the government wing than were near it. Your argument protects enormous steps toward expanding government influence by wrapping it in the emotional argument of “what about the poor and sick”, who are only a fraction of those who receive more money from the government than they pay in. It is the equivalent of using slogans like “support the troops” to put illegal wars beyond criticism.

“The most salient illustration of the issue is a parent walking next to a busy street with a child. The child, excited by something on the other side of the road, runs into the street and his parent grabs him by the arm to pull him back. This is certainly a use of force as the parent grabs the child’s arm and physically moves him back onto the pavement, but only an incredibly loose definition of violence would include this act. Furthermore, any definition of violence which includes this act would seriously cast doubt on the idea of all violence being morally wrong as this action hardly seems to be wrong.”

Force is not violence in this model because a child is not a fully-grown adult possessed of all adult rights to independent action free from the coercion of others, but an actual adult is, and their being taxed is still coercion (which is I think a better word for describing taxation than violence but which still encapsulates the intended negative connotations). Your example is thus one in which force would almost certainly not result in violence, because the child is not in any way being harmed or deprived of property and the child does not possess the cognitive ability to reasonably resent parental control. Your model does not accurately reflect the relationship between a taxpayer and the state, because in the case of paying taxes the taxpayer (child) is harmed and deprived by the government (mother) for no direct personal benefit in many circumstances (unlike the child who was saved) and perhaps even for personal loss in the case of the frequent misallocation of government resources. Your model also advocates, perhaps subconsciously, for the infantilization of the people as the children of the motherly state who knows what’s best and can guide her children to safety. The reality is that the government is often composed of incompetent, pensioner, paper-pushers toiling away their days in a mind numbing, Kafkaesque bureaucracy with very little conception of how to best guide the practices, and best spend the wealth, of private workers and entrepreneurs. Your model puts the government in the position of nearly omniscient overseer to the unknowing childlike people, when in fact the reverse is (or should be) the case in a democracy of well-informed citizens.

“And it should go without saying that taxes not being a moral institution does not mean that they are an immoral one. There are many things which exist which are outside the scope of morality entirely (e.g. traffic laws). These sorts of things merely exist out of organizational efficiency, i.e. we get better outcomes from having traffic laws (or, possibly, taxes) than if we do not.”

But you have not proven that we get better outcomes by taxation in all cases. It is not necessarily the case that government funded charity would do better to help the truly needy poor than private or religious funded charity, or that they do a better job of distinguishing between the truly disabled and the freeloaders. Also, speaking of government intervention as a means of improving “organizational efficiency” is laughable. Do you remember the last time you went to the DMV? How would you honestly rate the quality and efficiency of the service? I am not advocating for no help for the needy, in fact, because I sympathize with their plight I want to seek out the best and most efficient way of bringing them the most high quality service, healthcare, food, housing etc…as possible. There is little evidence though of government efficiency in providing any such products or services, and ample evidence of private charity being able to do so. Here is one interesting article: http://www.fee.org/the_freeman/detail/the-shortco…

And a good quote from that article:

“Indeed, the market economy has virtually eliminated extreme poverty in the United States. The average poor American lives a lifestyle that would be envied by most of the world’s citizens. But this is a product of the market economy not government handouts. It is only through wealth creation, not wealth distribution, that we see the wellspring of human progress”

You use, in opposition to Hudson (whose views on voting I do not support) the example of a “parallel argument [that] would run something like this: “if you caught someone forging a check of a value greater than $500 and imprisoned him in a room in your house for four years that would be fine? It is noteworthy that we call one case illegal kidnapping and the other justified punishment, but they are effectively the same.”

But a true libertarian would not punish non violent fraud with jail time, either privately or publicly funded, but would advocate for compensation for damages in such a case (like the fine you mentioned, which could be legitimately collected by the victim) and, if in your parallel case a violent crime were being committed, would advocate for the use of private force in defense if absolutely necessary. So it is not ridiculous to say necessarily that the government should largely be confined to the same restrictions as an individual, except in the limited circumstances of running functional and minimal police and military forces and courts.

“I would think that most people without a radical religious or philosophical stance would probably agree that there are certain limited cases where violence is permissible.”

Most people would, and libertarians contend that the state should be limited in its use of force to acquire tax revenue in order to use violence only in the few permissible cases where it is necessary, such as direct defense of the nation or defense of individuals from violent crime, but such forced taxation is not permissible when the taxes are used for some reason other than these certain, exceptional circumstances. Force is not justified in the acquisition of the wealth used to create most government programs that do nothing to immediately protect citizens from violence.

These are just some criticisms that come to my mind at the moment, perhaps I’ll comment further later.