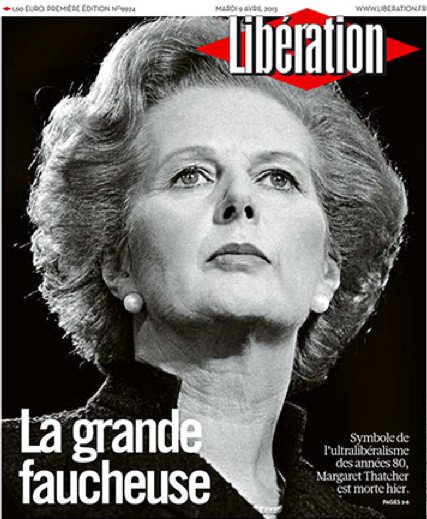

Margaret Thatcher is dead, and hagiography on the former British Prime Minister—brilliantly interrupted by Ken Loach’s petition to privatize her funeral—has already piled up to stratospheric heights. I would not be surprised if her spirit, like Chávez’s, announced itself to David Cameron in the form of a bird. I wonder what sort of bird though.

Before I go on and for the sake of full disclosure, let me clarify my stance on Thatcher. As a social democrat I find her politics unsavory to say the least, and as a Monty Python fan her incapacity to understand the dead parrot sketch makes me loathe her just as much on a personal level. Having said that I have always understood the respect Thatcher commands. It is no small feat for the daughter of a grocery store owner to make it all the way to Prime Minister, much less for a woman in the 1970s to rise through the ranks of Britain’s political establishment –and eventually come to dominate it. Thatcher was a first-class political animal. She is still remembered as the iron lady, but the nickname is misleading. Iron rusts easily, becomes brittle and snaps under pressure. Thatcher was more likely forged out of the same alloy as the Terminator. Much to its shame, the left today lacks a comparable symbol.

And now, for the fallacies of Thatcher hagiography.

The Thatcher saga’s foundational myth was her bold commitment to crack open the heads of a few miners who, in contemporary newspeak, had become over-entitled moochers. While the episode is remembered as a first victory for the underdogs of (economic) liberty over the entrenched power of postwar unions, the real story is different. The decision to take on the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) took place after the 1982 Falklands War, which boosted Thatcher’s approval ratings from a record-low 23%. Thatcher simply applied her wartime experience to the domestic front two years later, claiming that “[w]e had to fight the enemy without in the Falklands. We always have to be aware of the enemy within, which is much more difficult to fight and more dangerous to liberty.”

In other words, for Thatcher state terrorism was preferable to strikes, and dealing with the NUM amounted to war by other means. I am reminded of Tony Judt’s powerful observation:

These days, we take pride in being tough enough to inflict pain on others. If an older usage were still in force, whereby being tough consisted of enduring pain rather than imposing it on others, we should perhaps think twice before so callously valuing efficiency over compassion.

Moving on, the bulk of Thatcher hagiography is directed at her contribution as a pioneer of the “free market revolution.” This narrative, however, is false on both accounts.

First, Thatcher pioneered nothing –and neither did Ronald Reagan, for that matter. The first “free market revolution” took place in General Augusto Pinochet’s Chile. In the aftermath of a brutal coup d’ètat on September 11, 1973, and following Milton Friedman’s advice, Pinochet conducted an overnight liberalization of the country’s economy, with results that ranged from mixed to catastrophic. Thatcher merely followed the trail blazed by her friend, although in private correspondence with Friedrich Hayek she acknowledged British “democratic institutions” would not allow for liberalization at gunpoint, making the process “seem painfully slow.” She fortunately found the patience to bear with the market distorsions generated by democracy.

Second, what took place was not an economic revolution, but a counter-revolution aimed at crippling some of the Bretton Woods system’s greatest achievements, such as the welfare state and the countercyclical management of the economy. Thatcher and Keith Joseph’s economic policies constituted a break with the immediate past as a much as a return to the Gilded Age. Unsurprisingly, but in stark contrast with the postwar period, they produced huge rises in inequality. They also transformed the “workshop of the world” into a FIRE economy, and it is hard to look back at Thatcher’s economic legacy with much sympathy after 2008.

Finally, many of Thatcher’s policies remain unsellable regardless of the spin, and are therefore overlooked. Her foreign policy consistently fell on the wrong side of history. Thatcher qualified Mandela and his fellow ANC members as terrorists; supported Pakistan’s Zia-ul-Haq; armed Saddam Hussein, then turned back on him; became a euroskeptic and opposed German reunification. She also remained a good friend of Pinochet, visiting the general during his home arrest and crediting him with “bringing democracy to Chile.”

(Side note: Chilean President Sebastián Piñera has nevertheless praised Thatcher. This is the same Piñera whose brother José privatized the whole of Chile’s pension system while serving as Pinochet’s Secretary of Labor. José Piñera is now a distinguished senior fellow at the Cato Institute.)

What, then, does Thatcher’s legacy amount to? “Her greatest achievement” took place after her own party forced her to step down as Prime Minister in 1990: the influence of Thatcherism has since spread across the entire political spectrum. The right has not moved beyond Thatcher’s ideas in the UK or anywhere else; David Cameron’s “Big Society” is little more than a rehash of the 1980s “ownership society.” An irony, given Thatcher considered no such thing existed in the first place.

And after 1990, there was no left left. Britain’s Labour Party genuflected before her shrine throughout the 1980s and 90s, embracing the third way and following Thatcher’s TINA doctrine: the notion that “there is no alternative” to the liberalization-deregulation-privatization trinity. Progressives followed suit in Europe and elsewhere, and for the past thirty years have failed to articulate a counter-narrative.

But Thatcher’s political heirs are pygmies next to her. And their ongoing crusade against the welfare state is reckless, blundering into what even she understood to be third rails for social staibility. In doing so Europe’s Merkels and Camerons are playing with fire. Now Margaret Thatcher is dead, and the TINA consensus becomes more rusted and brittle with every passing day. What is to be done when it snaps?

Where are all the feminists rallying around Thatcher? I guess because she believed in things like free markets that makes here anti-women.

are you serious?

The Reaper | Brown Political Review http://t.co/q8srpLRM7H

Oy, che. Perhaps read sources other than Naomi Klein once in a while and maybe your analyses won’t be so one-sided. Pinochet was shit. Obviously. But To say Allende – as that Candian socialist 🙂 does in her article – was some heavenly angel put at the head of government by a starry-eyed popular consensus is, well, largely wrong. Allende got a paltry plurality of 36.2% of the vote, barely edging out his next competitor at 34.6%. “La vía chilena” then, was a disaster. With his price controls, wanton spending and reckless property seizures (though, I do feel for the fact that a lot that property was illegitimately seized by rich government cronies in the first place) managed to plunge the country into inflation rates of ~140%, a GDP that – even though it factored-in the insanely bloated government spending – managed to contract at over 5% a year after just one year of his presidency. Debt and deficits soared, reserves crashed and further socialist responses to this crisis worsened it.

Do I think Thatcherism/Pinochet are the answer? Not in the slightest. In large part they were “small” government and “big” government wherever it suited them, unduly benefiting the financial sector (as modern conservatism tends to do with its misguided “deregulation”) and – yes – leading to large amount of income inequality. But is nationalization and price controls the answer? Surely these are more reactionary and outdated than any economic liberalization you percieve.

Klein is a big fan of all things Latin American and socialist… The Shock Doctrine ends with a very unconvincing defense of Hugo Chávez. Hmph. Not trying to rescue Allende’s legacy though (which is why he is not mentioned), just challenge some of the Maggie myths.

Sure, sorry misunderstood that, though the benefits/negatives of the transition from Allende to Pinochet do have importance. His regime shifted inflation from the quadruple digits (sorry for the low-balling figure in my first comment) to ~10%, leading to higher purchasing power for citizens. It engaged in a largely succesful priviatization of social security, etc. Most privatizations were to political cronies et. al. so they weren’t as good as they used to be, but growth came with ‘evil capitalism’, and the poverty rate was halved as a result, even as some measures of wealth inequality grew. (Again, not defending the brutalness of the regime, we’re just talking econ.)

With Thatcher, I mean, she grew govt – not only in law and order but also in such social-justice-y fields as healthcare and social security – by over 12%, and specific sectors by as much as 30-50%. So her ails cannot be all dumped at the feet of misguided austerity. One of the biggest ‘capitalist’ initiatives she engaged in was corporate privatization in many strategic sectors, like steel. The problem was, this wasn’t what lead to the development of a largely FIRE economy per sé. British Steel was largely unprofitable before the privatization, and only severe cuts put in place by a government not keen on subsidizing inefficient unions and underutilized factories put it on the path to good business. Notably, pre-nationalization steel manufacturers were profitable and employed thousands. Perhaps it was the previous governments that put Thatcher in an unwinnable position by nationalizing industry, and they are the ones that put Britain on the FIRE path.

Paraphrasing Gandhi, capitalism is a good idea.

Goddamnit Jorge… 🙂

RT @BrownBPR: The Reaper: Thatcher Does Not Sow. Margaret Thatcher is dead, and hagiography on the former … http://t.co/uMT3AJLTgy