There was an ominous silence after Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) finished asking Dr. Arindrajit Dube her question.

“If we started in 1960 and we said that as productivity goes up — that is, as workers are producing more — then the minimum wage is going to go up [at] the same [rate],” said Warren. “The minimum wage today would be about $22 an hour…With a [current federal] minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, what happened to the other $14.75? It sure didn’t go to the worker.”

Dube, an assistant professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, was testifying at the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) March 14 hearing, “Keeping up with a Changing Economy: Indexing the Minimum Wage.” He responded to Warren’s question by presenting another query: What would the federal minimum wage look like if it had kept up with the wages of the highest taxpaying bracket? In that scenario, it would be a remarkable $33. Implicit in Dube’s answer was that while nobody knows for sure where every cent went, it is clear that the rich got richer while the poor got poorer.

A day later, House Republicans voted unanimously to defeat a proposed amendment to the Republican-backed SKILLS Act. Introduced by Rep. George Miller (D-CA) and jointly sponsored in the Senate by Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA), the amendment would have raised the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to $10.10 over the next two years.

Warren had been acutely aware of the approaching vote. She later clarified that the point in asking her question was to show that the proposed and ultimately defeated increases to the minimum wage were minuscule compared to what the wage should be from an economic standpoint. Warren was rejecting the claim of “inflationary effects,” which suggests that minimum wage increases inflate the costs of running a business that spill over and damage the economy as a whole. This argument against increasing the minimum wage is commonly used by conservatives and businesses owners, including a restaurant owner who testified at the committee hearing. But for liberals, as Dube remarked, “It’s uncontroversial that a minimum wage increase [to $10.10] would not have a [noticeably negative] impact on the economy.”

Other witnesses who did not favor a minimum-wage increase shuffled awkwardly as they faced Warren and Dube’s questions, and it looks like the discomfort is increasingly justified. These questions, the shot-down proposal for a $10.10 minimum wage and President Obama’s State of the Union Address that called for a minimum wage of $9 are all beginning to leave the realm of rhetoric and create a basis for real policy. Though Miller and Harkin’s efforts have been largely defeated for now by the Republican bloc, President Barack Obama’s Secretary of Labor nomination, Thomas Perez — who as attorney general of Maryland pushed for increases to the state’s minimum wage — signifies that the left is mobilizing against the opposition.

The Republican response to this mobilization is perhaps best exemplified by Sen. Paul Ryan’s comment: “I wish we could just pass a law saying everybody should make more money without any adverse consequences. The problem is you’re costing jobs from those who are just trying to get entry-level jobs. The goal ought to be getting people out of entry-level jobs into better jobs, better-paying jobs.”

The left and the right thus differ vastly on how an increase in minimum wage would affect the economy. Who is correct? Is it the liberals who argue increasing the minimum wage would give productive workers more buying power, which would in turn stimulate the economy? Or is it the conservatives claiming that a higher minimum wage would cause all workers to want an increase in wages, meaning that employers would have to cut back on hiring employees, especially low-skilled ones, in order to manage those demands — a result that would ultimately hurt workers and stifle the economy?

Research points both ways. The issue is at once incredibly economically complex and politically loaded, so studies often are partisan and conclude on either extreme; the Koch brothers’ libertarian Cato Institute as well as the National Employment Law Project (which also runs the website raisetheminimumwage.com) have conducted exemplary conflicting studies in that regard.

In February, the Washington Post ran an article exploring why economists disagree so much about the implications of increasing the minimum wage. The Post found that the theoretical model from Econ 101 that raising the minimum wage would increase unemployment by increasing the cost of hiring low-pay workers and therefore causing enterprises to cut back on such employees is just not empirically true. Drawing from the careful work of John Schmitt of the widely revered and nonpartisan Center for Economic Policy and Research (CEPR), the Post highlighted that the majority of studies show that gradually increasing the minimum wage actually has little to no effect on the economy. This is because when wages are increased, there is less worker turnover. The possible corresponding slight decrease in wages for higher-paid employees and rise in consumer prices are offset by the lack of screening, training and vacancy-related costs that would otherwise result from worker turnover, which means companies do all right.

Despite the fact that the majority of nonpartisan research points to the conclusion that gradually increasing the federal minimum wage would not hurt the economy as conservative critics suggest it would, the political reality for any increase at the federal level is gloomy. Every time a Democrat has proposed increasing the federal minimum wage or indexing the wage to inflation, Republicans have killed their efforts. Tellingly, the last time the right did vote in favor of increasing the federal wage — but not indexing it to inflation — was in 2007 under President George W. Bush. Considering that increasing the minimum wage results in workers spending more, high school enrollment increasing and public health improving, one might gather that conservative objections are not made with public interests in mind. In essence, Republican concerns about low-paid workers amount to little more than inflammatory rhetoric when faced with the facts. Nevertheless, Republicans control the House and have filibustering power in the Senate, so there is little hope for minimum wage reform on the federal level.

On the other hand, some states have taken the lead in increasing minimum wages for workers. Since 2007, 19 states and Washington, D.C. have passed minimum-wage laws that surpass the federal amount. On the higher end of the spectrum, New York and Maine have recently passed laws to increase the state minimum wage to $9 over the next few years. The states with the most progressive minimum-wage laws have their minimum wages indexed to inflation. This includes Vermont, which has a radically higher employment rate than that of most states. The Miller–Harkin federal minimum wage proposal, following Vermont’s example by indexing the wage to inflation, would have had the same results as the state did: little to no negative impact on the economy and a better-paid working class with higher spending power.

The federal government has a history of following states — the laboratories of democracy — when it comes to the minimum wage. Massachusetts became the first state to introduce a minimum wage in 1912, but it took until 1938, during Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency, for the federal government to adopt its own minimum wage law, the Wages and Hours Bill. Roosevelt understood the significance of this policy, declaring during one of his fireside chats that “except perhaps for the Social Security Act, it [was] the most far-reaching program, the most farsighted program, for the benefit of workers that has ever been adopted, here or in any other country.”

The federal minimum wage established by Roosevelt increased steadily until the early 1970s when, with less political support in a bad economy, it began to decline. That trend continued until the 2007 Fair Minimum Wage Act, which passed thanks to unusual Republican support. Then, the federal minimum wage was set to rise over the next two years, from $5.15 per hour to $7.25 per hour.

Despite this victory for workers in 2007, another federal minimum wage increase is long overdue. Unlike the generations before them, Americans today who are paid the minimum wage have few chances to lift themselves out of poverty. In real terms, 1968’s minimum wage would today be $10, equivalent to annual earnings of $20,000 assuming an average of 40 hours a week. In contrast, working for the present federal minimum wage of $7.25 now barely amounts to making $15,000 a year, well below the official U.S. poverty line for a family of four at $23,550 per annum. Although raising the minimum wage to $20,000 a year would still not be enough for such a family, even those few thousand dollars would mean a great deal.

Warren helped call attention to this unfortunate absurdity in the Senate HELP committee hearing, and others in government are doing their part as well, suggesting brightness ahead rather than the gloom of the status quo for a federal minimum wage increase. Although her point about a $22 minimum wage was a tactic specifically to push for the $10.10 standard indexed with inflation, its broader effect may be long-lasting. There is certainly an audience for her maneuver: according to a poll done by USA Today and the Pew Research Center, 71 percent of Americans support increasing the federal minimum wage to $9.

Gradually increasing the minimum wage, as many on the left have been pushing for, would not burden the American economy. With a higher minimum wage, companies would see reduced worker turnover costs, education enrollment would increase, public health would improve and fewer people would be living in poverty. Indeed, granting lowest-paid workers’ claims to higher wages may, in time, become less a far-fetched policy proposal and more a necessity for politicians to support if they want to remain in power.

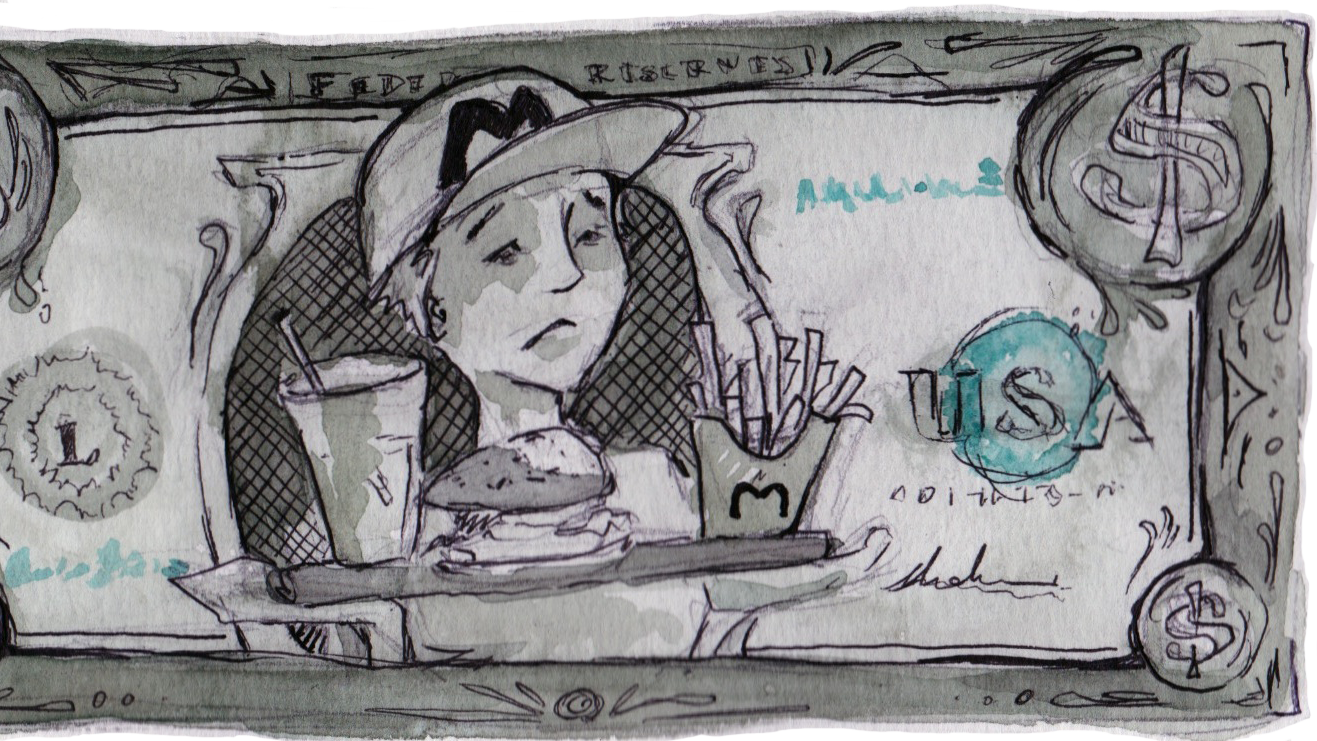

Art by by Emily Reif