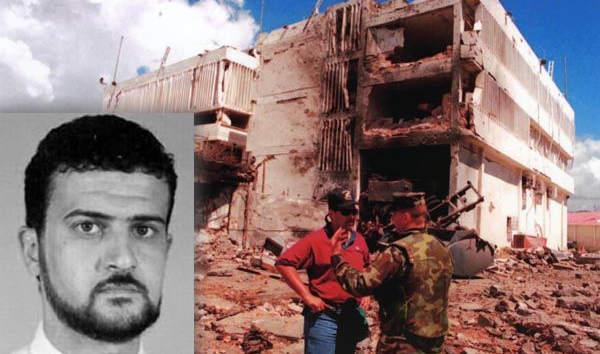

On Saturday evening, I found myself tailgating at Brown Stadium, lamenting aloud how much it would suck to go to URI. At some point, I looked down at my phone and saw a news alert. After reading that the U.S. government had conducted two separate military operations with Special Forces in two separate countries, I was dumbstruck. Why the concurrence of these events? Is the Natty Light jaundicing my interpretation of their significance? Perhaps, but both of these operations – the successful capture of Nazih Abdul-Hamed al Ruqai (commonly known by his nom de guerre, Abu Anas al-Liby) in Tripoli and the aborted capture operation on an al-Shabaab compound in Somalia – are significant on a number of levels. Let us focus on the legal considerations surrounding the former. Specifically, the model utilized for al-Liby’s capture elucidates a powerful solution to some of the most pressing legal inquiries surrounding detention in the War on Terrorism.

In 2000, al-Liby was indicted in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York for his role in the 1998 African Embassy bombings. Specifically, testimony gathered from two cooperating former al-Qaeda militants established that al-Liby was in charge of running the organization’s computers; that he also set up a darkroom for developing photographs; and that he further was on the street of the U.S. Embassy in Nairobi in possession of a camera. This is in addition to a terrorist training manual, “Military Studies in the Jihad Against the Tyrants,” which British police seized from al-Liby’s apartment and which has been admitted as evidence in other federal criminal trials. Therefore, it appears that on both the individual – to the extent he was intimately involved in a lethal attack on U.S. targets – and organizational – to the extent he was a member of al-Qaeda – levels, al-Liby is a lawful target under the 2001 Authorization for Use of Force Against Terrorists.

Consequently, as the Supreme Court established in Johnson v. Eisentrager and confirmed in this context in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, the U.S. could lawfully detain al-Liby under the laws of war “until the end of hostilities.” However, the Obama administration has instead decided to subject him to periodic naval detention and interrogation, followed by transfer to and criminal prosecution in Manhattan federal court. Notwithstanding the assertions of some hawkish senators to the contrary, this option is preferable both as a matter of law and policy. First, the location of long-term detention presents practical and legal difficulties. The administration could utilize the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay but has rejected doing so for a number of reasons, including the president’s promise to close it and its international reputation’s deleterious effect on net counterterrorism effectiveness. Furthermore, as a result of the National Defense Authorization Act’s restrictive transfer provisions – which the Republican House instituted as an out-of-principle rejection to federal criminal prosecution of terrorists – sending al-Liby to Guantanamo for any period of time would effectively consign him to the military commission process forever. Even more, the Supreme Court’s extension of habeas corpus to Guantanamo in Boumediene v. Bush means that any governmental effort to sustain his detention would require the divulgence of potentially significant operational intelligence.

If the Obama administration’s concerns were truly particular to Guantanamo, however, it could also transfer al-Liby to Afghanistan for long-term detention. Indeed, some have dubbed the U.S.’s detention facilities there as a second Guantanamo Bay. This is because in al-Maqaleh v. Gates, the D.C. Circuit denied the justiciability of habeas petitions from Afghanistan on the grounds that unlike Guantanamo, it was a ‘hot’ battlefield. However, a closer examination renders this option practically and legally unfavorable as well. Concerning the former, the Afghan government – which has been exercising increasing control over these facilities in preparation for American withdrawal – has resisted the transfer of foreign detainees. In addition, the al-Maqaleh holding is by no means finalized. Beyond a potential Supreme Court examination of its distinction from Boumediene, the D.C. Circuit expressed their willingness to revisit al-Maqaleh either in the event of excessive foreign transfers or as the U.S.’s withdrawal undermines its status as a ‘hot’ battlefield. As a result, the administration has pursued a hybrid, laws of war/criminal prosecution model with al-Liby, one that is derived from the detention and prosecution of Ahmed Warsame.

Special Forces captured Warsame in the Gulf of Aden in 2011. He was detained pursuant to the laws of war, with the High-Value Detainee Interrogation Group (HIG) interrogating him on a naval vessel for intelligence purposes. It is true that Article 22 of the Third Geneva Convention requires detainees be held only on land. This is inapplicable, however, since it applies only to prisoners of war in international armed conflicts, requirements that al-Liby and Warsame plainly do not meet. Following this period, the Red Cross was notified and given access to him; a new team of FBI interrogators entered and Mirandized him; and he was transferred to the U.S. for presentment and criminal prosecution. Charged with numerous terrorism-related crimes, Warsame cooperated and entered a guilty plea. There is a strong argument for similar success in the al-Liby case. First, while statements to the HIG may be inadmissible in court because they were involuntary, they would retain their intelligence value. Second, assuming these statements were indeed inadmissible, the HIG interrogation ought not affect subsequent statements made after Mirandization. Since the differentiation between intelligence and prosecutorial interrogation is so stark in this scenario, a federal court would be hard pressed to conclude that al-Liby’s later statements were compromised by a “taint of involuntariness” from his prior ones.

This model’s success depends on two primary variables: the feasibility of capture and the likelihood of successful criminal prosecution. Because the fall of the Qaddafi government gave al-Liby the perception of safe haven in Tripoli, for example, the U.S. was able to successfully launch a capture operation in a relatively accessible area. Second, the wealth of admissible evidence the government already possesses in the case of al-Liby – due to his involvement in and the pending indictment surrounding the 1998 bombings – is abnormal. Without this confidence in successful prosecution, the potential costs of not securing cooperation post-capture are heightened. Thus, the Warsame model is underinclusive, and cannot be applied in every circumstance. Nevertheless, intransigent hawks who insist on detention at Guantanamo and liberal critics who assert this process is “extralegal” are both misguided. Indeed, this hybrid model possesses distinct advantages over either the civilian or military approaches utilized alone, and presidents and Congresses should embrace it wherever possible.