It is a question that has long been asked in America, particularly after the handling of firms after the 2008 crisis, and most pressingly after 2010’s Citizen’s United Supreme Court ruling: are corporations people? The answer, for innumerable reasons, seems to me to be a resounding no. But that is beside the point, for I believe there is another question that soon must be debated around the world, particularly with the growth of state-owned investment vehicles known as sovereign wealth funds. Corporations are certainly not people – but can states be corporations?

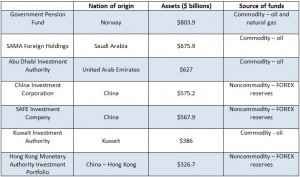

A cash-laden Kuwait created the first national sovereign wealth fund (SWF) in 1953. Kuwait was awash with money from their oil productions, and, seeking to invest rather hold unprofitable bills and bonds, founded the Kuwait Investment Authority. Today, the fund holds assets valued at $386 billion.

The number of sovereign wealth funds, though still accounting for only a little more than three percent of global investment pools, has increased by 25 since 1998. The funds explicitly cut out the here-to-fore most fundamental intermediary between the state and the market — the private sector.

This direct state-market relationship defines the nature of SWFs, and just like state pension funds, they carry all the political risks one could imagine.In 2006, Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra sold his family’s controlling share of the Shin Corporation, a Thai telecom conglomerate, to the Singaporean SWF Temasek Holdings. The result was a political firestorm, as many accused the prime minister of selling out a national champion, and ultimately Thailand, to a competitive neighbor.

Also in 2006, the acquisition of the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Company, which controlled several major American ports, by Dubai Ports World, a ports terminal operator located in the UAE, brought intense criticism to the Bush administration. The reason? Dubai Ports World was an asset of Dubai World, an Emirati sovereign wealth fund. Many couldn’t believe that terminals at American ports could be leased by an Arab nation. Dubai Ports World sold their control of terminals soon after. In 2007, on the eve of the looming financial crisis, the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority invested $7.5 billion in Citigroup. When things went sour less than a year later, the merger came under intense scrutiny, and is still being contested in court today. And in Germany in 2008, Angela Merkel’s CDP passed a bill that called for intense scrutiny of any foreign SWF takeovers of German firms if they posed a threat to “national security.”

Sovereign wealth funds typically fall into two camps. Many, like the Kuwait Investment Authority or Saudi Arabia’s SAMA Foreign Holdings, are the result of massive oil and resource revenues. Others, like the China Investment Corporation or China’s SAFE Investment Company, are the result of exceedingly large holdings of foreign exchange reserves. A key issue for SWFs, across all manner of assets and investment strategies, has been transparency. According to some matrices, there is a clear correlation between the transparency of a fund and the political nature of its government. Democratic nations tend to have more transparent SWFs. Perhaps the most notable one of these, unsurprisingly, is in Norway. Their Government Pension Fund, often referred to simply as “The Oil Fund,” ranks high on measures of transparency. Perhaps most notably, the fund is know for its ethical investing. Norway’s SWF has divested from such companies as Lockheed Martin (because they make bombs, and lots of them) and Reynold’s American Inc. (because they make tobacco, and we all know what that can do).

The politicization of wealth is hardly a novel issue. But the ways in which states today handle their wealth, outside the realm of central banks (SWFs are more often than not outside the jurisdiction of these banks) and legislative halls, are fraught with political potential. Sovereign wealth funds, by any measure, do not really post a threat to the national security of any nation. To argue as such seems protectionist. But their increasingly engaged presence in global markets and politics does indeed raise questions about the role of the state in an altogether financialized world.