A majority of Americans have now begun to embrace human embryonic stem cell (hESC) research. With each report of a new successful application of stem cells to a medical use, Democrats and Republicans alike are further recognizing hESC’s biomedical importance. Over the last few decades, hESC therapy has been used to further research on a wide variety of ailments – including spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, infertility and even hearing loss –generating largely promising results.

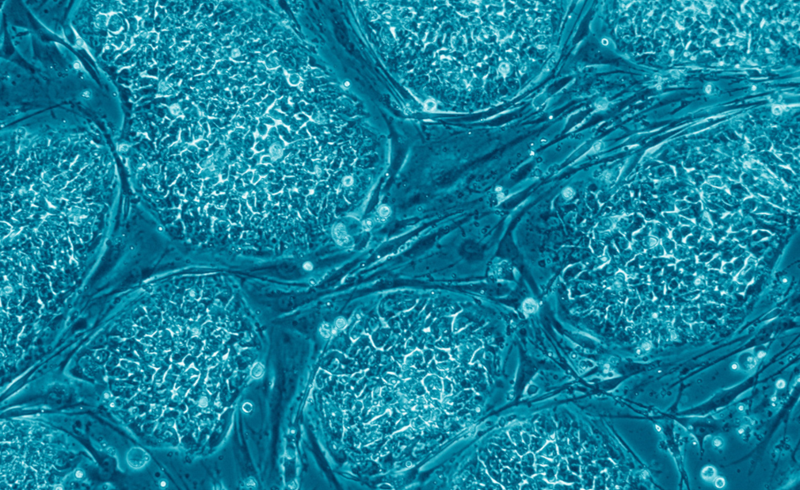

The controversy with hESC research does not center on the results but the methods, a moral dilemma that has been debated in the media for years. Embryonic stem cells are derived from four to five-day-old blastocysts, hollow balls of cells that represent the beginning stage human embryonic development. The extraction procedure results in the destruction of a human embryo, one that has been voluntarily donated in a fertility clinic. But the huge potential of these cells has caused scientists, most politicians, and 72 percent of the general public to come to terms with this fact.

Although, over the last two to three years, embryonic stem cells have, more or less, crawled off the media’s agenda, they remain hindered due to one small piece of decade-old legislation.

Since 1996, Congress has passed the Dickey-Wicker Amendment — a clause attached to the yearly budget appropriations bill for the Department of Health and Human Services. This mandate disallows funds from being allocated towards research that involves the destruction of a human embryo. Because the usage of human embryos is necessary for the creation of hESCs, the 17-year-old amendment has significantly confined the breadth of scientific research that can be done in the field.

In 2009, after years of disapproval from factions of Congress, President Obama issued an executive order that expanded funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for research on embryonic stem cells. However, because of the Dickey-Wicker Amendment, the executive order stipulates that research must still be exclusively conducted on stem cells that come from an NIH-approved list of existing stem cell lines (lineages of stem cells that are derived from a common embryo). While this policy change has opened up opportunities for scientific advancement, hESC research, even with the executive order, is still restricted in one crucial way by the Dickey-Wicker Amendment: new stem cell lines cannot be synthesized. The list of approved stem cell lines is publicly available in the NIH Human Embryonic Stem Cell Registry. The registry reveals that there are currently 261 eligible hESC lines eligible for government-funded research. While 261 may seem like a decent number, the number of useable cell lines is not as great. Some of these stem cell lines have been frozen, thawed, and refrozen for years on end, and are thus not suitable for research. Furthermore, because many of the stem cell lines have been deliberately mutated and were created for a specific research project spearheaded by a specific institute, they are not often useful to the average researcher. Curiously enough a small number of institutes, including Harvard and a private Australian cell bank called Genea, have created a large proportion of the approved stem cell lines,. Other entities, like the Reproductive Genetics Institute, have never had any of their many submitted cell lines approved. The same database shows the list of stem cell lines that are pending NIH approval. Some of these lines have been under review for nearly four years, confirming that the NIH approves more fundable cell lines at a sluggish rate at best. Do the costs of creating human embryonic stem cells, outlined in the Dickey-Wicker Amendment, outweigh the benefits of a more comprehensive, useful, and thriving field of stem cell research?

So what is the big deal with publicly funded researchers working on only a restricted assortment of existing stem cell lines? Firstly, a singular stem cell line that is constantly passed down between laboratories and researchers has a high likelihood of accumulating genetic mutations or chromosomal anomalies. Although hESCs can divide indefinitely, their utility decreases after years of experimentation. Additionally, the risk of contamination can lead to poor results and misguided conclusions. Though hESC lines share common characteristics, such as the ability to differentiate and rapidly reproduce, they differ in many other regards. Some lines respond better to certain types of cell culture, while others show little success in actually differentiating (morphing) into other cells. Swedish scientists have found that at least 3 percent of expressed genes differ in a collection of 25 – seemingly identical – stem cell lines. Therefore, researches who can only use a limited variety of stem cell lines are not able to explore the full potential of stem cell therapy, for they lack the most crucial resources — diversity. Since biomedical disorders are complex and multifaceted, these limitations are a large setback.

The second issue with the small number of stem cell lines available for research is less well known but highly consequential. A University of Michigan research team analyzed 47 of the most commonly used embryonic stem cell lines and found that a majority of these were derived from donors of northern and western European ancestry. None of the lines came from donors of other ethnicities. The therapies and medical treatments that result from hESC research may react differently to various ethnic and racial groups, due to genetic or epigenetic (environmental) factors. Therefore, it is necessary for researchers to experiment with hESCs that are derived from donors of all ancestries. Otherwise, advancements made with stem cell research may be applicable to only a small subset of the US population. This, in the words of one University of Michigan researcher, is a “social justice issue.”

The Dickey-Wicker Amendment, though only a small legislative rider to the Department of Health and Human Services’ appropriation bill, has and will have long-term effects on human embryonic stem cell research. Researchers need to expand the number of stem cell lines they work on, but, under current legislative restrictions, the list the NIH offers does not permit them to do so. The question that ultimately arises is complex: do the costs of creating human embryonic stem cells, outlined in the Dickey-Wicker Amendment, outweigh the benefits of a more comprehensive, useful, and thriving field of stem cell research? The research that is currently being done to find methods of hESC creation that do not destroy embryos is one way out of this dilemma, but will not yield conclusive results any time soon. The way forward, then, is to bring the Dickey-Wicker amendment back to the negotiation table after 17 long years.

The NIH proposed expanding the definition in 2010.

http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/booster_shots/201…

This expanded definition was then challenged in court and tied up for three years.

http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/01/07/us-usa-…

Now 1.5 year later and the redefinition still has not taken place.

It seems that a lawsuit has been successful in it’s goals via delay and time forgets.

The NIH has had over a year to act on an initiative they were ready to move on in 2010.

What has changed? Political will, Public support?, IPS cell hope?

It just seems a shame when a court battle achieves it’s goals even when it loses in court.

But I guess that is a pretty common theme in out court system.

Meanwhile, The people suffer.

Actually stem cells have been created without destroying the embryo using a method similar to PGT (Pre-implantation Genetic Testing). These non-destruction of embryo stem cells are extracted during the “Blastomere” (6-8 cell) stage and leave the embryo intact without destruction. Currently, a company named Advanced Cell Technology has several lines on hold at the NIH waiting for approval because of the wording in the NIH definition of stem cell does not cover this technique. So besides the Dicky-Wicker amendment, there are other political pressures at play behind the scenes.

http://grants.nih.gov/stem_cells/registry/pending.htm?sort=orga

See the asterisk on The Advanced Cell Technology submissions under review and the definition statement at the bottom of the page.