By James Konsky

On December 7, 1776, British forces made landfall at Newport, Rhode Island. The young Brown University, until then sheltered from the violence that plagued the colonies, was quickly affected. James Manning, the president of the University at the time, wrote that the Royal Army “marched for Providence, there, unprovided with Barracks they [sic] marched into the College & dispossesed the Students.” Though this event marked the beginning of Brown’s physical involvement with the conflict, the sentiments that swirled around it had been felt at Brown since the college’s inception some 15 years before.

Much of this revolutionary fervor had revealed itself in the commencement ceremonies of the college’s early years. During Brown’s formative period, commencement activities involved more than a simple ceremony and included active discussion amongst students and faculty. Many of the dialogues and debates that occurred at these early commencements centered on America’s independence, or the troubling lack thereof. The Commencement of 1771 featured discourse on the topic of the “Necessity of perpetuating the Union betwixt Great Britain and her Colonies.” Following that example, members of the class of 1775 wrote a petition to the Corporation of Brown University which described how they were “deeply affected with the Distresses of our oppressed Country, which now most unjustly feels the baneful Effects of arbitrary power.” One Commencement ceremony, however, stood out above the others in terms of its revolutionary spirit.

At the college’s first Commencement in 1769, Manning and the candidates for graduation provided a sincere interpretation to the idiom “wearing your heart on your sleeve.” While receiving their degrees, they wore “clothes of American manufacture” as a tangible means of protest against the perceived injustice of British trade laws. The gesture was the first recorded instance of student activism in the history of an institution that has since become synonymous with challenging discourse and civil dissent.

That day, the locally made graduation gowns were not the only manifestation of the thickening tension between those who wanted colonial independence and those loyal to the Crown. The most pressing topic of the commencement debates was the burning question: Should the American colonies separate from Britain to form a new nation? One of the debaters was a 20-year-old honors student, James Mitchell Varnum. On that summer day in 1769, Varnum was tasked with arguing that America should remain a colony of Britain, and he did so with verve and tenacity. This performed stance, however, was a far cry from both true sentiments.

In that small, restless class of 1769, four of the seven graduates would go on to volunteer to fight for the cause of American independence, but Varnum would do more to set himself apart than all the rest combined. In the early years of revolution, he became active in military affairs, helping establish the Kentish Guards of East Greenwich, Rhode Island. Varnum quickly distinguished himself among the ranks of the Continental Army, rising to the post of brigadier-general, most notably commanding the 1st Rhode Island Infantry and 9th Continental Infantry. Under his deft leadership, these regiments would win major victories at the Siege of Boston and the Battle of Valley Forge. As both a successful soldier and leader in the fight for independence, his most enduring legacy would be one very consistent with Brown’s progressive tradition.

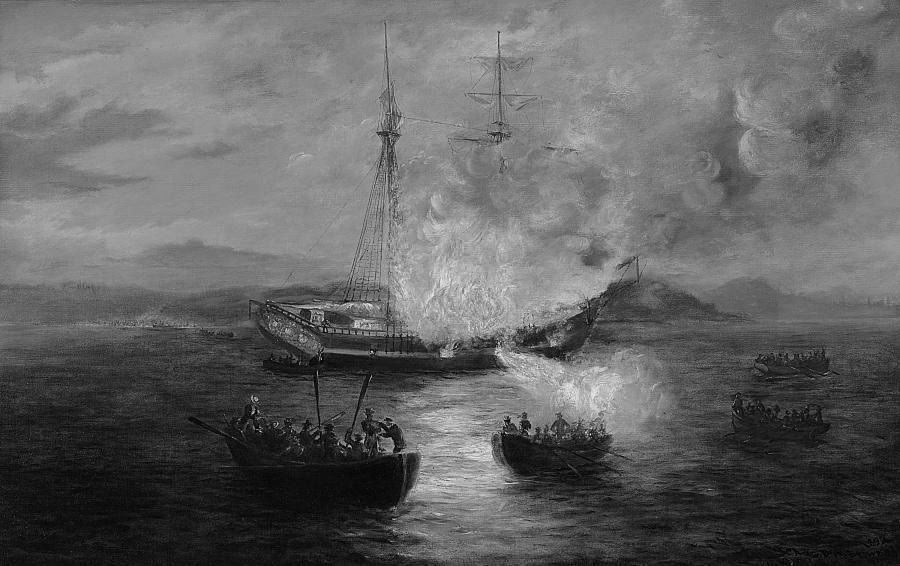

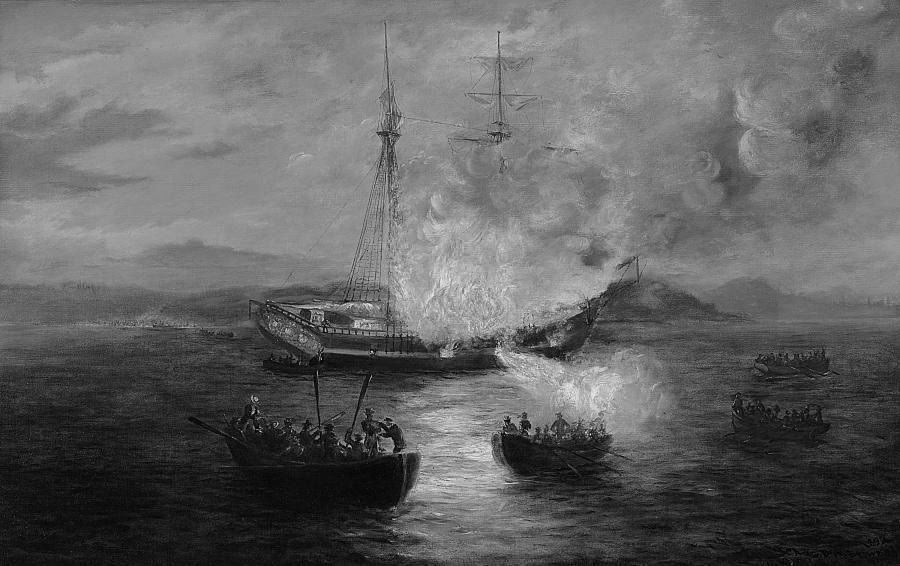

Slavery is a devastating reality of the history of both Brown and America. The Brown family — the benefactors who would later give their name to the University — made their fortune in the slave trade. As such, it is impossible to discuss Brown’s beginnings without acknowledging the cruel associations surrounding the University’s formation. James Mitchell Varnum again stands as a symbol of Brown’s progressive nature, representing another dimension of Brown’s relationship with slavery. At the height of the revolution, he advocated for the inclusion of slaves into the Colonial Army. Varnum pressed to allow African Americans the opportunity to enlist in the army, despite the fact that they were subjugated at the time. No doubt partly pressured by the state’s difficulties with recruitment, the Rhode Island Assembly voted to allow slaves to volunteer for combat. In exchange for their service, these volunteers were to be granted their freedom. Varnum’s 1st Rhode Island Infantry became the first military regiment to include African Americans — by the end of the conflict, 140 of them marched against the British.

By the end of the war, the University had lost three graduates, missed six years of classes and paid thousands of dollars to repair University Hall after the battles that took place in Rhode Island. The Corporation reconvened in September of that year to once again settle down to the business of charting a course for the University, now part of a new nation. There was one piece of revolutionary activism left, however, as the Corporation passed a resolution to destroy the royal seal in University Hall. Consequently, an institution that had been founded by royal charter less than two decades previously cast off its colonial identity.

Professor Walter Bronson, author of “The History of Brown University, 1764-1914,” noted in his book, “In [revolutionary] times, and in such a center of rebellion, the college could not remain unaffected or impassive.” Affectedness and impassivity have remained constants in the two and half centuries that have followed Brown’s founding. Born as it was in a time of turmoil, the University has long since upheld the idea that progress is often the result of conflict: Whether in the military struggle against a colonial oppressor in the 18th century or the intellectual clash of ideas that characterizes the college today, Brown has rarely failed to encourage the fruitful, although sometimes tense, conflicts that lead to — quite literally — revolutionary change.