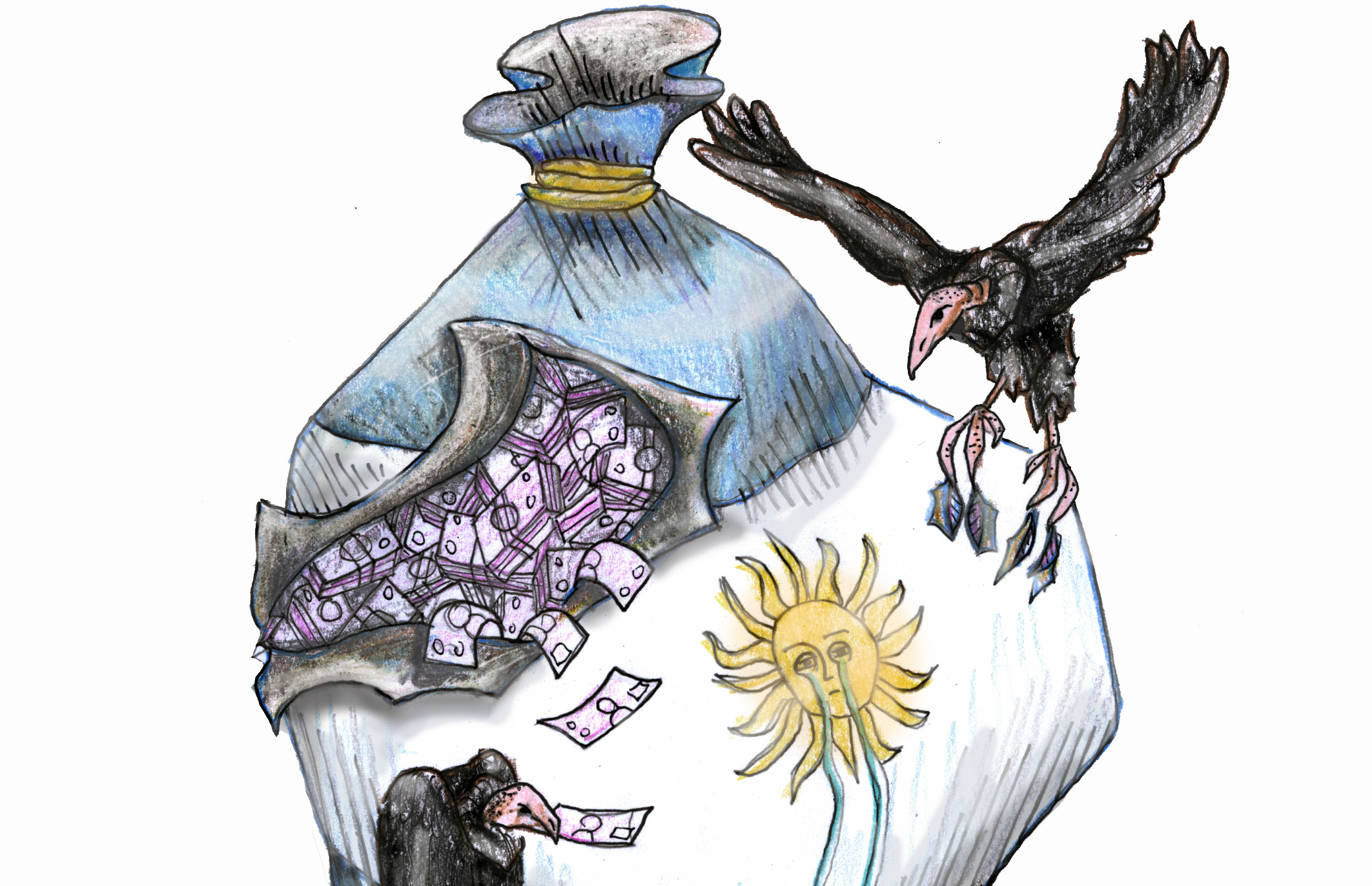

On his deathbed, Oscar Wilde is reputed to have quipped, “I am dying as I have lived — beyond my means.” This sense of gallows humor is no doubt one that strikes a nerve with Argentines everywhere as the country slips into default for the second time this millennium. The first default arrived in 2001, at the tail end of the Argentine Great Depression, when the Argentine economy shrank by 28 percent and millions of jobs disappeared. While the two debt defaults are separated by a mere 13 years, time is not the only source of intimacy between the two economic disasters. The second crisis is, in many senses, a case of Argentina’s vultures returning home to roost.

Early in September, the United Nations General Assembly passed a potentially historic piece of financial legislation. The resolution aimed to address sovereign debt — national debt held in foreign currency — by establishing “an intergovernmental negotiation process aimed at increasing the efficiency, stability and predictability of the international financial system.” The decision may not have the most inspiring prose, but it could reshape the landscape of the international financial system on a divisive issue: the recurring problem of sovereign debt defaults. An impactful resolution might allow the UN to establish some equity in an increasingly zero-sum and lawless system.

Despite being the cause of so much toxicity and strife, sovereign debt remains ubiquitous in the world today. While the history of debt is an elaborate one that stretches back several thousand years, sovereign debt defaults are relatively novel. Perhaps the most telling default in antiquity was the case of Rome after the Punic Wars. Though successful, the wars fought against Carthage came with an enormous cost to Roman coffers. Faced with the prospect of being unable to pay its debts, the Roman government decreased the amount of metal in its currency from 12 ounces to 2. Effectively, the currency suddenly devalued by a factor of six — roughly the same impact as turning 1970 dollars into 2014 dollars overnight. As such, the Roman government could mint coins at one-sixth the previous cost and was thus able to pay off its debt with relative ease. This strategy, known as currency debasement, was an extremely popular solution for overextended governments beginning in the ancient world. Debasement was made possible in large part due to the fact that most debts were denominated in local currency. But as debt went international, things became much more complicated.

Two millennia later, sovereign debt defaults have proliferated due to the belligerent maelstrom that was Europe and the brittle economies of newly independent nations that emerged when colonialism collapsed. Civil wars, international conflict and the flowering of the modern financial market — in which countries can borrow from private investors by selling bonds internationally — have sent government borrowing into the stratosphere, and this surge has brought a similar increase in debt defaults. Though time has passed since the Roman affair, sovereign debt defaults are now more widespread than ever. But while the time-tested problem is still around, the time-tested solution — allowing central banks to manipulate currency values in order to avoid default — can no longer be applied.

By the 19th century, currency debasement had fallen out of vogue. While the Roman government in 200 B.C.E. could afford to arbitrarily devalue its currency by simply stripping out more than 80 percent of the metal content, things are not so easy for modern governments. For starters, national debts are often denominated in currencies the debtor does not have control over, most commonly the US dollar or the euro, meaning that the government in question cannot drag itself out of a debt hole by tampering with the currency. For example, if Argentina issues its debt in US dollars and doesn’t wish to pay it back, the Argentine government can’t force the US Federal Reserve to print enough dollars to substantially devalue the US currency. Borrowing in international markets takes the form of selling bonds, which carry an interest rate and entitle the buyer to be paid back the original price of the bond — plus interest payments — by a certain date. As such, debt issuance is equivalent to taking out a loan. Because bonds can be sold through any exchange, they can take on the form of any currency.

Even if a country has control over its own currency, many creditor-debtor relations are already internationalized— creditors from countries like the United Kingdom have holdings anywhere from Bangladesh to Bolivia. Well-coordinated and powerful creditors, with military and naval power to boot, would not accept any currency manipulation measures that might prove unbeneficial to their own holdings. Venezuela discovered the bellicose nature of this system in 1902: In order to protect their economic interests, British, German and Italian warships simply blockaded the nation’s ports until Venezuela paid its debts. Caracas’ predicament is equally valid for today’s Argentina, as powerful international creditors also threaten the country’s livelihood — though the menace now consists of fewer warships, and more lawyers.

Debt settlements have increasingly involved compromises between a national government and international creditors. Since defaulting on debt hurts a country’s creditors as well as the indebted nation itself, last-minute restructuring deals are the name of the game. The concessions made in these deals by creditors to overburdened debtors became much more frequent as global markets became increasingly interdependent. Argentina has had experience with this mode of dealmaking since its default in 1890, when private British creditors lent the country millions of pounds in order to grease the wheels of repayment. The same creditors subsequently agreed to restructuring that involved a short-term reduction in interest payments when that loan proved insufficient. The successes of such techniques were amply reapplied over the years, as they not only provided debtors more flexibility in fulfilling their obligations, but also gave creditors more security and stability in their investments. By the time Argentina defaulted again in 1982, the processes of renegotiation, restructuring and rescheduling had become the bread and butter of the sovereign debt scene.

Today’s crisis mirrors the 2001 Buenos Aires default. Back then, Argentina faced the worst economic conditions it had ever seen, and the government was unable to pay off its multibillion-dollar international debts. The country’s economy had been mired in recession for a few years prior, due to the domino effect of the Russian and Brazilian financial crises, and it had been dancing on the edge of default since the 1990s. Among a confluence of tipping points, the refusal of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) — which had been propping up the Argentine economy with loans for nearly a decade — to continue lending forced the country over a financial cliff. A few days before the curtains closed on 2001, the Argentine national government defaulted on $82 billion worth of loans.

The value of Argentine bonds, the country’s sovereign debt, plummeted as investors desperately tried to offload them onto the secondary debt market — where investors who had originally bought the debt could resell it at a discount. A few plucky financiers, however, continued to purchase Argentina’s debt, hoping to utilize the nation’s increasing inability to manage its finances in order to reap massive profits by going against the flow. Following its crippling default, Argentina became a nest of opportunity for vulture funds — investment firms that explicitly focus on buying distressed sovereign debt following a default. Though these financiers know that the debt is unlikely to be paid back at full value, their goal is to prey on desperate governments’ need for cash, build up a large portfolio of bonds and then sue the desperate government for the full value owed. This field was opened up by a 1996 court case involving Panama and a hedge fund called Elliott Associates. Run by billionaire investor Paul Singer, Elliott Associates successfully sued Panama for almost the entirety of the expected return on its bonds and used this lawsuit as the inspiration to later force an entire series of national governments to meet their full debt obligations. As others took after Elliott Associates’ example, a simple formula was crafted: Buy the debt of countries teetering on the edge (or already over the precipice) of default at a steep discount and sue those countries in court to force payment as close to full debt obligations as possible. The method marked a profound departure from the practice of renegotiating debts that had built up over the previous century.

Singer’s unconventional strategy has been outrageously successful. In the case of Panama, his firm bought $28.7 million of debt for a sale price of $17.5 million and eventually collected $57 million from the Panamanian government by claiming the repayment of the original debt plus fees and interest. Argentina’s case is even starker. The debt now controlled by Elliott Associates is one example in a pool of debts held by investors with similar strategies and is now worth $630 million at face value, though the company only paid $48 million for it originally. The sum of debts owed by Argentina to holdout investors, however, is now $1.5 billion; with interest and fees added on, it could even end up being as much as $3 billion. Given how much the country is already struggling to stay afloat, being forced to pay the full amount could cripple many of the government’s vital functions.

Argentina is desperate not to meet the same fate as Panama, especially since the country’s decision to default on its debts was designed to establish a clean slate for its troubled economic policy. Elliott Associates’ holdings originally accounted for a tiny portion of the $82 billion that the country defaulted on back in 2001. The debt that didn’t make its way into the hands of vulture funds went through the same process of renegotiation that was common throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Through restructuring deals that dragged on until 2005 and 2010, the creditors agreed to take a ‘haircut’ — or reduction — on these debts, and the Argentine government agreed to pay back the debt at this renegotiated price. Argentina’s government has honored the haircut terms. Or rather, it has attempted to.

Using an impeccable understanding of international and local laws, Elliott Associates and similar vulture funds have made it impossible for Argentina to settle its debts through conventional means. Because the 2001 debt default was issued in New York, it falls under New York law, and in the heat of the legal tussle between the investors and Argentina, the former won a crucial skirmish by utilizing the nuances of New York regulations. Judge Thomas Griesa of the Southern District Court of New York ruled that Argentina could not pay the majority of its creditors until it had paid the holdout investors, named as such because they did not accept the restructuring deals that Argentina had already negotiated. Following a failed appeal to the US Supreme Court, Argentina was forced to either pay the $1.5 billion it owed or default. Unable to finance the burden, the nation defaulted in July of this year.

Argentina’s latest default has brought the conflict between creditors and indebted nations to yet another impasse. The Argentine government continues to condemn the holdout investors as thugs holding a nation of 40 million for ransom, while Singer and his fellow investors, aside from pursuing profit, still believe that Argentina’s government is flying in the face of international financial law, threatening the global financial system as a result. Much of the holdout investors’ case pivots on the idea that they should be paid because the Argentine government agreed to the commitment when it borrowed the money in the first place. Singer also proposes an ethical dimension to the situation. A Bloomberg Businessweek profile on Singer noted that he “characterizes the case as a fight against charlatans who refuse to play by the market’s rules.” Singer has panned Argentina as being responsible for “horrendous government policies in many areas” and says that they would be flouting norms and getting off scot-free for their behavior if the state were allowed to renege on its commitments. The argument might come across as patronizing, especially in the face of the enormous payouts Singer would receive at Argentina’s loss, but it’s one that rests primarily on the international rule of law — if there’s no guarantee that a country will follow through on its obligations, then the sanctity of international contracts rests on thin ice.

Some of Argentina’s argument also relies on ethical reasoning, but Singer and the Argentine government unsurprisingly reach different conclusions. Investors might be legally entitled to the full payout, and though that may be the morally scrupulous thing to do, not only is it unfeasible, but it would also come at a devastatingly high human cost to Argentines. Argentina’s government certainly carries some responsibility; it’s hardly a model of democratic government, with the country ranked 106th in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index in 2013. Moreover, its misguided fiscal policies are what forced it to accrue this debt in the first place. Still, it is a legitimate question as to whether it is right, or even possible, to hold a nation of millions accountable for the corruption or incompetence of its leaders.

It’s worth mentioning that while around 92 percent of Argentina’s creditors accepted the terms of restructuring offered by the government in 2005 and 2010, the creditors weren’t given much in the way of choice. The options at the time were either accepting a haircut or not seeing a dime of their original investment. The terms offered weren’t exactly generous either — one otherwise sympathetic commentator described them as the “worst terms since World War II,” as investors had to accept only 30 cents on every dollar.

The holdout investors have said that they are willing to sit down with Argentina and hammer out terms; Singer himself claimed in an interview with the Wall Street Journal that “we could settle this thing in an afternoon.” But the need to keep up appearances may be standing in the way of a deal — if Singer capitulated and accepted the terms offered to the majority of creditors, then countries around the world that are nearing default would undoubtedly notice. For an investment strategy that hinges upon stubbornness, concession would set a precedent that would likely undermine the effectiveness of Singer’s tactic.

Although holdout investors have professed openness to renegotiation, further compromise may not be viable for Argentina. Even if the two parties could come together and hammer out terms tolerable to both sides, the nation would be legally obliged to extend the same improved offer to the 92 percent of creditors that previously agreed to restructure the debt they held. In short, Argentina’s costs of servicing the debt would skyrocket — an event that would have dire consequences for the country’s already troubled economy.

This is perhaps the fundamental difference between sovereign debt and almost all other kinds of debt: The risk associated with sovereign debt considers both the stakes involved with damaging the country’s population with the difficulty of making a national government do something it is not inclined to do. As a result, the rules are different and more fluid than for other types of debt. Holdout investors may claim that the Argentine government is violating international finance regulations, but before 1996 and the Panama case, the de facto rule of sovereign debt defaults was that creditors and debtors renegotiated to terms that were more likely to be equal sacrifices for both sides. This dealmaking is also a process that can go on for years, while both sides haggle endlessly until they strike a bargain. Often the terms are not kind to creditors, but this is an implied risk of buying sovereign debt and the primary reason why such investments carry high interest rates to begin with. The lawless landscape of sovereign debt means that every transaction and interaction between creditor and debtor is laced with uncertainty. Perhaps some sort of wide-reaching regulatory apparatus is necessary.

The thought of getting caged in a similar predicament to that of Argentina concerns many countries, particularly developing ones, who fret that what little procedure there was to sovereign debt default has vanished. This anxiety was the propelling force behind a UN resolution recently passed for “the establishment of a multilateral legal framework for sovereign debt restructuring processes.” Introduced by Bolivia on behalf of the Group of 77 — a group of developing nations banded together in a sub-UN intergovernmental organization that includes China, Brazil, India, Indonesia and Argentina — the resolution passed with a strong majority: 124 in favor, 11 against and 58 abstentions.

Although the strong numeric majority would suggest that a supranational regulatory structure for sovereign debt could be in the works, the countries that rejected the proposition are key. The United States, the UK, Germany and Japan all opposed the measure. It’s no coincidence that the nations with financial centers like New York, London, Frankfurt and Tokyo are keen to avoid more regulation. Tellingly, a spokesperson for the United States “stressed that she could not support a statutory mechanism for sovereign debt restructuring as such a mechanism was likely to create economic uncertainty,” and urged renewed efforts to go through established global channels like the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The desire to avoid uncertainty is an admirable and agreeable one, but it’s too little, too late: The reality after Panama and Argentina is mired in uncertainty anyway. Calls to use the IMF as a conduit for reform are fine as far as they go, but they don’t go far. IMF management has a past full of failed attempts and a reputation for draconian measures. And since it was unable to establish a sovereign default restructuring mechanism in 2003, despite a robust effort, there’s no guarantee that it could reform its practices going forward. Though a decade has passed since these reform attempts collapsed, the issues surrounding sovereign debt remain the same — countries with significant financial centers prefer to keep decision-making power at home. Financial industry initiatives, like the International Capital Markets Association’s proposal to include clauses obliging all debt holders to go along with any restructuring deal that 75 percent of the relevant holders accept, have also come out of the woodwork. Plans like these would prevent situations like Argentina’s, but would also fail to address the underlying problem: the lack of an overarching solution for the disorder that occurs after a sovereign debt default.

Final judgments must be kept waiting until a full picture of the framework proposed by the UN emerges, but it’s an encouraging step towards a secure progression of responses to sovereign debt defaults. The nonbinding nature of UN resolutions means that such a process is no doubt a long way off; a resolution serves more as a memorandum of understanding than anything else and would require independent changes in legislation by each signatory. Furthermore, the opposition of big money centers will likely prove a significant hurdle to making this an effective measure. Nonetheless, the enthusiasm of emerging international powerhouses like Brazil and China — countries whose debt levels have soared in recent years — means that progress may be viable even in the short term.

The crux of the international sovereign debt issue is the delicate balance between debtor and creditor. If the global system leans too far to one side, unrest and unruliness are bound to follow. When the debtors have the upper hand, there is no accountability for mismanagement, and creditors withdraw their resources from the pool of capital that debtors need access to. If the imbalance leans too far to the creditors, debtors will experience a downward spiral as default feeds into default and legal and monetary losses pile up. The actions of Paul Singer and his peers — morally debatable but not technically illegal — have upset this balance. While debt and death were synonymous for Oscar Wilde, the world cannot subject its developing nations to the same misanthropic fate.

Art by Amanda Googe.