“Unbelievably stupid,” is how one senator referred to the program designed in the aftermath of 9/11 to completely revamp our intelligence gathering in the Middle East. “This is just wrong,” declared another. The project to which they are referring is the Futures Markets Applied to Prediction (FutureMAP).

Initially rolled out in 2003, FutureMAP was an effort to address the apparent deficiency in communication among intelligence agencies that the 9/11 terrorist attacks had revealed. While the nation was reeling from the attacks, many were outraged by the discovery that there was intelligence indicating the government knew of the plot. As the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Against the United States’ report on 9/11 said: “By September 2001, the executive branch of the US government, the Congress, the news media, and the American public had received clear warning that Islamist terrorists meant to kill Americans in high numbers.”

FutureMAP was designed to try to address this failure in intelligence sharing and analysis by applying the principles behind an age-old stalwart of finance — the futures market. In essence, a futures market is an auction in which participants buy and sell contracts that promise delivery of a commodity on a specified date in the future. According to economic theory, the estimates generated by the market’s prices reflect all known information and therefore provide the best prediction of future events. As Nobel Prize winner Fredrick Hayek explained: “The mere fact that there is one price for any commodity…brings about the solution which…might have been arrived at by one single mind possessing all the information which is, in fact, dispersed among all the people involved in the process.” To the Bush Administration looking for a better, more efficient way to generate predictions from disparate information, the power of futures markets seemed like a perfect tool to apply to intelligence gathering in the Middle East.

Further encouraging the Bush administration in this pursuit was the fact that futures markets had already been applied to electoral politics through the Iowa Electronics Market with great success. The Iowa Electronics Market is a futures market that, in essence, allows people to bet on the outcomes of elections. If you believe a certain candidate will win, you buy a contract of that candidate at the going rate. What is different about this market is that, unlike a gambling ring, this market does not pay you according to the odds that the candidate will win. Instead, a win produces a constant value (such as, for example, $1). Prices are determined by the demand for the contracts, such that a race that is expected win will cost $1 and a long-shot race will be worth closer to one cent. By observing the prices of the contracts, one can therefore deduce what the market believes the probability of a win for that candidate will be. Incredibly, this mechanism has been tremendously successful at predicting the outcomes of elections — far better than polls and rival to Nate Silver’s legendary statistical prowess.

The Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) decided that if it could gather enough experts on the region and have them all bet on the probability that certain political events like assassinations, coups, or foreign policy announcements will occur, the US government might have a new way to generate robust intelligence about the Middle East. As one professor who helped design the program said: “Intelligence is about spending money in order to find out information about gruesome things like war and terrorism. This is just an alternative institution that tries to aggregate intelligence information.”

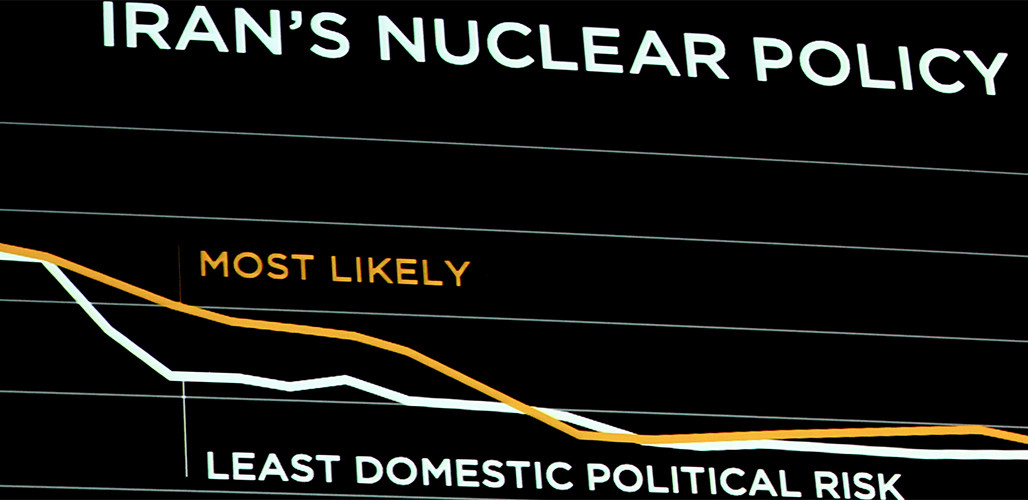

Excited by the potential for this idea, the Bush Administration hastily went about setting up a futures market on the Middle East. By summer of 2003, FutureMAP was ready to enroll 1,000 participants, with the target of growing to 10,000 participants by the beginning of 2004, at a cost of $8 million. It would allow participants to buy futures in economic, civil and military events in Egypt, Jordan, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria and Turkey. Examples on the site included the likelihood that the King of Jordan would be overthrown and that Yasser Arafat would be assassinated.

The only snag in the program’s set-up occurred when the existence of the market became widespread knowledge. Immediately after the New York Times broke the story, the political left went wild. The prospect of allowing Americans the ability to bet money on the chances of a foreign leader’s death seemed to be insensitive at best and a diplomatic crisis in the making at worst. As Senator Byron L. Dorgan of North Dakota said: “Can you imagine if another country set up a betting parlor so that people could go in — and is sponsored by the government itself — people could go in and bet on the assassination of an American political figure?”

Also troubling was the fact that anyone could buy futures and potentially profit in this market. While conceptually targeted towards Middle East experts, actions in the market were completely anonymous. Thus, many were worried that a form of insider trading could occur: terrorists who were already plotting to commit an act of terror could buy futures in that action to profit from their crimes or worse, someone could be incentivized to carry out an action in order to make it big on the market.

Proponents of the market, like George Mason University economics professor Robin Hanson, argued that such an action “would mean that [the terrorists] are giving up information to gain money” and thus it would act like a bribe which is “kind of like normal intelligence gathering.” Other experts didn’t want to take the risk.

The program stirred intense controversy in the public and in Congress. The Bush Administration immediately recanted and scrapped the program, acknowledging some of the problems with its setup. Given the pressures the intelligence establishment was under to clean up its act after 9/11, it’s no surprise that the agencies were enticed by market-based solutions to their woes. However, the FutureMAP program was naive in its design from the start. As Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle said, “I can’t believe that anybody would seriously propose that we trade in death…How long would it be before you saw traders investing in a way that would bring about the desired result?” In its pursuit for more complete information, the government could have set up a system that incentivized the very behavior it was fighting two wars to stop — acts of terror.

That said, the intent of the program was spot-on. For better or for worse, the United States is inextricably linked to the Middle East. Spending the better part of the last decade fighting two wars, launching air strikes, providing aid, and getting a good portion of our oil from the region, the United States has a huge stake in its political developments. It follows that obtaining accurate information continues to be a top priority for the government, and recent events only further emphasize the need for our government to look for creative alternatives to traditional forms of intelligence gathering. Unfortunately, FutureMAP just wasn’t the solution.

This piece is part of BPR’s special feature on terrorism. You can explore the special feature here.