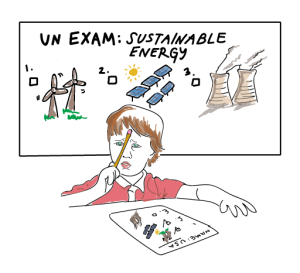

We cannot afford to lose another decade,” warned the chairman of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in April 2014, explaining how critical it is for countries around the globe to seriously consider efforts to reduce the effects of climate change. If the world is to take dramatic action, the United States must take a leading role. Today, solar, wind and geothermal power account for just 6 percent of US energy production. Unfortunately, the American public remains wary of one of the most promising energy alternatives: nuclear power. Though not a silver bullet for the climate crisis, nuclear power provides carbon-free electricity on a large scale, which the United States desperately needs.

Once a prime target for the ire of the flower power generation, nuclear power has begun to gain wider acceptance, but a fear of nuclear energy remains embedded in the American consciousness. Security hawks on the right and ardent environmentalists on the left remain equally skeptical. The former group worries that terrorists will target reactors or that enemy states can too easily convert civilian nuclear programs into sources for atomic bombs. The latter faction is wary of the dangers of nuclear waste and is opposed to proliferation on principle. This partially explains why, in a rare point of bipartisan compromise, lawmakers on both sides — from Sen. Harry Reid (D-NV) to Mitt Romney — came together to oppose the primary long-term solution to the problem of radioactive waste: Yucca Mountain.

Americans weren’t always so opposed to nuclear power; in the 1950s and 1960s, the Atoms for Peace program helped the United States develop the world’s largest civilian nuclear program. But one month in 1979 would change the public perception forever. In March, “The China Syndrome” opened in theaters, portraying a meltdown at a nuclear reactor and its disastrous consequences. For many viewers, it was the first time they had been confronted with this possibility. Within 12 days of the movie’s release, a reactor at a nuclear plant on Three Mile Island sustained a partial meltdown. Though no one died, and the amount of radioactive matter released was not dangerous, the event remains seared in American minds. There has not been a major incident at a US plant since, but paranoia over nuclear energy remains, kept fresh by accidents at Chernobyl in Ukraine in 1986 and Fukushima in Japan in 2011.

Yet many of nuclear power’s opponents overestimate the likelihood of a meltdown. All cases have involved an improbable combination of poor regulation, out-of-date design, operational negligence and bad luck — and each remains an anomaly in the history of nuclear energy. The assumption that nuclear power plants are just waiting to fail comes from a fundamental misunderstanding of the plants’ technology and the undue vehemence against their use.

Furthermore, nuclear reactor technology has made major advances since Three Mile Island. Today a new generation of nuclear scientists is tackling the challenge of designing fail-safe reactors. The latest ones include mechanisms that would prevent catastrophes like those in Ukraine and Japan. Three such innovations, which industry insiders collectively refer to as advanced nuclear reactors, are molten salt reactors, pebble-bed reactors and fast neutron reactors. Each presents an excellent opportunity to make up for the shortcomings of the standard Cold War era light water reactors.

While not a new concept, molten salt reactors have emerged as the most promising avenue for nuclear innovation. Unlike light water reactors, molten salt reactors do not run the risk of pressure-related explosions like those that occurred at Fukushima or Chernobyl. These reactors can also run on fuel too degraded for typical nuclear power plants to use — including the waste from conventional reactors, offering an innovative and productive solution to today’s problem of nuclear waste. Additionally, because they can run on nuclear fuels other than uranium, molten salt reactors address the concern that reactors can be used to generate weapons-grade nuclear material. Several companies have been working to bring molten salt reactors to the market, amongst them Transatomic Power and Flibe Energy.

Although molten salt reactors are currently the most marketable solution to outdated reactor designs, pebble-bed reactors and fast neutron reactors also carry advantages that make them safer to operate than conventional technologies. Pebble-bed reactors are better designed to deal with the heat released by accidents, limiting the effects of any potential problems. In addition, proponents say they would have lower operating costs than traditional designs. While fast neutron reactors carry high costs and require high levels of uranium enrichment, they are also much more efficient than the current technology, producing little waste with comparatively low toxicity levels.

The federal government must now step in to encourage nuclear entrepreneurs with financial backing as well as technical and regulatory support. However, that won’t be easy: The Nuclear Regulatory Commission has only had to deal with one kind of reactor and is wholly underprepared to certify and monitor plants that use these new technologies. Moreover, the Department of Energy (DOE) will need to devote more funding to loan guarantee programs and other forms of project financing in order to encourage research, development and implementation in the nuclear energy field — only 8 percent of the DOE’s current budget goes to new reactor research. And the United States must move fast: Two domestic nuclear energy companies have already moved their testing facilities to China, while major research developments are already underway in countries like Norway and Japan.

Nuclear power is not a perfect energy source, and the path ahead — developing and installing safe nuclear reactors — will be complicated and challenging. Nevertheless, if we are serious about preventing the disasters that climate change poses, the American public faces a choice: resign itself to the rising tide of catastrophic climate change or lift the clean energy sector up through nuclear innovation.