I am sitting across the table from Dr. Claire Andrade-Watkins, a documentarian and historian of the Fox Point Cape Verdean community with the Swearer Center for Public Service, in the Benefit Street Juice Bar and Café. This place, with its hip music, organic juices and college-aged clientele, is not how Andrade-Watkins remembers it. For her, this will always be Bob and Gloria Solomon’s store, where she would purchase bright penny candies after school as a kid. “This was where all my cavities started,” she laughs, pointing out the spot where the candy counter used to be, describing the malt balls and paper dot treats that are now only found in kitschy reproductions of old-time general stores. In its place, there is only an empty section of hardwood floor — any sign of the counter that used to sit there is long since gone.

The story is familiar across Fox Point: The small, family-owned businesses that catered to an immigrant community in the 1950s and 1960s have disappeared due to a series of initiatives that evicted residents in order to preserve historic homes and build a more modern neighborhood. The shops of the old guard have been supplanted by boutique coffee houses, record stores and art galleries that cater to a professional community largely composed of Brown University’s professors and students. What used to be a thriving, self-sustaining community of immigrants is now almost gone, existing only in the memories of the people who grew up there.

Immigration to the Northeast from Cape Verde started in full force in the mid-19th century. From 1860 to 1921, roughly 1,500 Cape Verdean immigrants arrived each year. Immigration continued fitfully after the 1920s, with a surge of migrants in the wake of World War II and another in 1965 after the Immigration and Nationality Act ended exclusionary policies on immigrants from African countries. Immigrants from Cape Verde came to the United States in droves on steamships, packet boats and small freight vessels, with many of these new Americans settling down in Providence’s Fox Point.

Fox Point’s Cape Verdean community long remained tied to the water, often working on whaling ships from New Bedford and Nantucket. In the 19th century, a significant portion of Nantucket’s whaling crews was comprised of Cape Verdeans. But even after the whaling industry collapsed in the 1920s, members of the community often continued to find employment at the port as dockworkers and longshoremen.

By the time a young Andrade-Watkins was walking along Benefit Street, the Cape Verdean residents had started many of their own businesses and forged their own community in Fox Point. The community was fairly isolated, largely due to a lack of access to Rhode Island’s educational and economic resources. As a result, Fox Point residents were forced to become self-sufficient, creating opportunities that were never given to them by others. Andrade-Watkins’ mother, for example, recognized the failings of education in Fox Point and sought to improve it. Her and others’ hard work was fundamental in creating the charter that eventually led to the development of Fox Point Elementary School.

It was actions like these that created the Fox Point community. Large, multigenerational families — many of which did not speak English — were its backbone. “We were all related,” Andrade-Watkins remembers. “When you have a community that’s intact, people know one another.” It may not have been particularly wealthy, but it was culturally rich, and the community was both cohesive and united. And, as Andrade-Watkins remembers it, because “everybody knew everybody,” there was barely any crime. According to Bobby Clarkin, who grew up in the area with Andrade-Watkins, “Crime was next to nothing…we never locked the doors.” Though hard data on crime is difficult to come by, Fox Point residents seem to have taken some steps to keep their community safe; young men, for instance, would go to the Fox Point Boys Club together each day after school, participating in activities that were designed to keep them out of trouble.

The Fox Point described by those who grew up there was different from how outsiders saw it. While to Andrade-Watkins and her childhood friends, Fox Point was a safe community of tight-knit and hard-working families, others considered the neighborhood synonymous with instability. The first omens of the impending gentrification appeared in the 1935 report by the Providence Redevelopment Agency called “Proposed Slum Clearance and Housing Project for Providence: South Main-Wickenden District.” The report concluded that Fox Point was in need of urban renewal and claimed that “the present population is unstable and employment is irregular.” While the suggestions of this report were not enacted, it set the precedent for the eventual renewal of the neighborhood. The report displayed what would engender Fox Point’s reputation as a slum that needed to be changed — and fast. In 1940, another report found that as many as 40 percent of the houses in Fox Point lacked private facilities or needed repairs — a statistic that was never revised as time went on, though it was used as an underlying basis for many claims about the problems in the community. However, conditions in the area nonetheless seemed to be improving: Two studies by the Providence Redevelopment Agency, in 1951 and 1961, noted major improvements on structures in the area over the decade, with these improvements almost entirely undertaken by residents themselves.

Nevertheless, the city began to take a few constructive steps towards renovating the Fox Point area in the years after the 1935 report. Plans for urban renewal in Fox Point only became a concrete reality, however, after a 1959 report was published by the Providence Planning Commission and the Providence Preservation Society entitled: “College Hill: A Demonstration Study of Historic Area Renewal.” Regarding Fox Point, the report states, “the study area contains overcrowded slums and neglected and worn out buildings.” Moreover, the report dismissed South Main Street, the cultural hub of Fox Point and the location of many small, family-run businesses, as “a mixture of junk shops and other poor grade commercial establishments interspersed with an occasional substantial business.” The College Hill report ultimately served as the basis for the East Side Urban Renewal Project, an effort that permanently transformed Fox Point when it was enacted in 1961.

The one characteristic the neighborhood had of value, at least according to the 1959 report, was the centuries-old colonial homes its residents occupied. However, those residents were already beginning to feel pressure to relocate. Brown was expanding quickly: Between 1940 and 1956, Brown purchased a number of new properties in order to build more dormitories and offices, as well as to clear land for Wriston Quadrangle. The central part of College Hill — the area surrounding Brown — already had some of the highest rents in the city. The College Hill plan sought to encompass Fox Point, where rents were generally low, in the expansion of the wealthier parts of College Hill. The goal was ultimately to transform the neighborhood in a way that would accommodate the ever-expanding University campus while pushing out the Cape Verdean residents from their valuable colonial homes and replacing them with wealthier residents who would provide a better tax base for the city.

It wasn’t just the beautiful homes or proximity to the University that sold the city on the College Hill plan. Urban renewal fit many of the city’s goals, allowing it to attract residents back into the city and fight rapid suburbanization. It also would clean up urban spaces in which the new, wealthier residents could live, thrive and pay taxes. But replacing the current residents meant having a reason to get them out, and the narrative of a poor, unstable community in Fox Point, which had begun with the 1935 report and continued throughout the years, provided the perfect base on which to overlay concerns about urban blight. Thus, a story was born: Fox Point was suddenly seen as not only an opportune location for urban renewal, but also as a place that genuinely needed it.

“You needed to rationalize, the same way you needed to rationalize Manifest Destiny,” Andrade-Watkins says of the PR movement that accompanied Providence’s urban renewal plans. The government was essentially advocating for displacing an entire community, and that meant changing how people saw the value of the community. But the plan worked, and the effect the idea had on the rest of Providence was powerful. “It created a hostile public perception in the newspaper for white people, for the power structure,” remembers Andrade-Watkins.

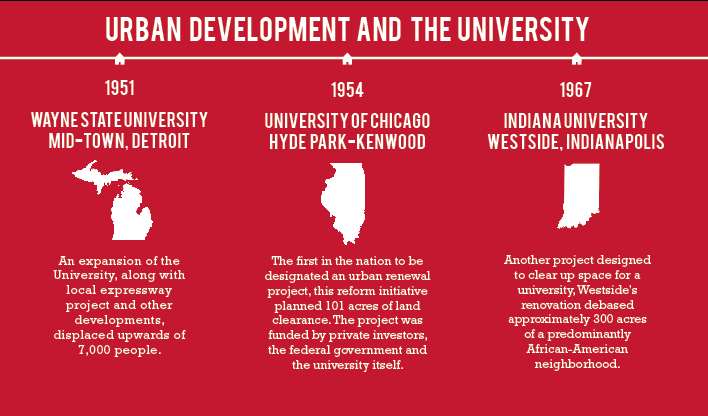

Although Andrade-Watkins’ story — and Brown University’s — is about Fox Point in particular, it certainly wasn’t a foreign concept. Urban renewal had taken the country by storm in the 1940s and continued to be a major force in the reorganization and redevelopment of cities across the country. But while Robert Moses was building bridges in New York City, the Providence government was busy burning them.

The result of the publicity campaign was a policy that preserved the houses in Fox Point, but not the people who lived in them. It was this intense practicality that Andrade-Watkins remembers as disturbing: “It was the buildings that were of concern,” she says. “Bricks and mortar. It was nothing about the people. Our value and community as a group was negligible.” Andrade-Watkins explains that the logic really came down to wealth, and that meant that the Cape Verdean community was seen as having little value.

Most Fox Point residents rented their housing, and the sudden push for preservation raised rent prices to unmanageable heights. Much of the district was rezoned from a multiple dwelling area, one that accommodated the sorts of families typical in the Cape Verdean community — like the one Andrade-Watkins grew up in — to one dominated by single family homes, precisely because they were more desirable to the types of people who were now supposed to move into the area: professionals who worked downtown, faculty and students.

Raising rents worked. Faculty from Brown and the Rhode Island School of Design bought many of the newly restored houses, both because they were conveniently located and because, having just been priced out from under a low-income community, they were relatively cheap. Students also began moving into the neighborhood: Between 1971 and 1978, the Brown student population in Fox Point increased by 66 percent. Over time, the original Fox Point residents were priced out of their historic neighborhood. The value of the neighborhood had risen rapidly: Houses bought for $3,000 to $12,000 were then regularly sold for $10,000 to $22,000 after renovation. Many who owned their houses were happy to sell for more money than they had paid and move to the suburbs.

But for the majority of Fox Point’s Cape Verdean community, the changes were devastating. As renters were forced to leave their homes, suddenly unable to pay for the buildings in which they had lived for so long, they struggled to find suitable alternatives. According to Andrade-Watkins, Cape Verdeans often faced rental discrimination in other areas of the city. Her parents were some of the last to leave their area of Fox Point, relocating from their house on Planet Street, where they had lived for 35 years, to Cranston in 1974. Over a dozen families within three blocks of Andrade-Watkins’ home were displaced and forced to find new homes, mostly in East Providence or the East Side near Camp Street. Andrade-Watkins describes the devastation as something more than just a story of individual families struggling with housing — it was an intergenerational loss. She remembers Fox Point as she saw it: a safe and pleasant community on the brink of entering the middle class, spurred onwards by burgeoning educational opportunities and the drive of its business-oriented residents. Her generation, she explains, would have gone on to college and careers elsewhere, and the neighborhood would have gradually changed as its residents found success. It didn’t need the urban renewal it had been prescribed. Instead, urban renewal stopped that gradual, organic coalescence and forced the Cape Verdean families to relocate — thereby dismantling the work of past generations. The community never recovered after being forced away from the self-sustaining neighborhood that had provided for them for so many years.

Fox Point’s problems, however, did not end with the East Side Urban Renewal Project. The concurrent construction of I-195 added to its destruction. The Federal Highway Act had promised to modernize infrastructure in the United States, just as the Autobahn had done in Germany. Eisenhower’s promise of one nation, indivisible, united by roads became a reality in cities across the country. But it also had less ideal consequences. Many marginalized neighborhoods became the sites for these new freeways, and Fox Point was no exception. The plans for I-195 began in 1947, and the construction commenced in 1958. Fox Point was in part chosen for its cheap land, but the construction of I-195 also played into the narrative of renewal: The highway would be a starting point for the redevelopment of a blighted area, an initiative that would help tear away the fabric of the old community and set the stage for a wealthier and better-connected one. The freeway construction resulted in the leveling of dozens of houses and businesses near the waterfront, which were seized through eminent domain to serve the project. Over 200 people were displaced by I-195, and Fox Point was severed in two, disconnecting the once-communal neighborhood. I-195 wreaked even further havoc on the community by slowing down business at the port. Although it had already been in decline due to containerization and industrialization in the 1960s, I-195 exacerbated the downturn.

Throughout the decimation of its neighborhood, the Fox Point community did not sit idly by. When builders constructed I-195 without any point of access to Fox Point, the neighborhood protested, gathering 1,037 signatures for the construction of the Gano Street off-ramp. Several hundred residents joined the Fox Point Neighborhood Association, founded by Charles Simon, and fought to preserve the neighborhood as they had known it. But the combined forces working against Fox Point were too strong. The Cape Verdeans were trapped by Brown University on one side and I-195 on the other. With the advent of the East Side Urban Renewal Project, they were forced out of their neighborhood altogether despite their protests. In Andrade-Watkins’ mind the small, marginalized community in Fox Point could never have withstood the institutional forces working against it, even when its members stood up to the big guns.

The biggest crime of the gentrification of Fox Point was not the theft of homes — it was the theft of history. Although the new residents have kept the name, they have also sterilized Fox Point’s past. The colonial legacy of Fox Point is preserved in the centuries-old homes and their commemorative plaques, but the history of the Cape Verdeans who occupied those homes between then and now is forgotten. “It’s a comfortable space,” Andrade-Watkins acknowledges, where the more uncomfortable aspects of the neighborhood’s history have been intentionally forgotten.

I can’t change the past. You know, I don’t have an ax to grind. But am I sad? Do I miss [it]? When I walk into Bob’s and Bob and Gloria aren’t here…when I pass my street that all of us grew up on…when I don’t see my childhood friends and didn’t grow up with them the last 50 years? Like our parents grew up together, from before they were born until their deathbed? Do I miss that? I can’t even begin to tell you how that feels.”

Today Andrade-Watkins finds Fox Point barely recognizable. If residents of the Fox Point that existed 50 years ago visited today, they might be surprised, or even horrified, to find places like Manny Almeida’s Ringside Lounge, once a gathering place for the community, turned into the now-closed Z Bar. But the damage has already been done, and the only question now is how to preserve the memory of Fox Point and the people who once lived there.

Andrade-Watkins, also an Associate Professor at Emerson College and Visiting Scholar at the Brown Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice, works to catalogue the experiences of the community. Her own memories of Fox Point, she understands, are only part of a much larger story, a complex network of friends, family and neighbors who have now moved on. She stresses that because of this intricate history there is no definitive truth in the story of Fox Point, and that her work alone could never fully represent the countless stories of the Cape Verdeans in Fox Point. “What I have done is put together, through my work, something that reflects the sense of the community and is inclusive. But in no way does anybody have the authority or the imperative to be the voice, either for us or of us.”

The Fox Point story is neither isolated nor over. Neighborhoods across the United States — from Boston’s West End to Chicago’s South Side to Los Angeles’ Bunker Hill — whisper similar stories of gentrification and eviction at the hands of powerful institutions. But the history of Fox Point is important for us to remember as residents of Providence and as Brown students who benefit from this institution and its efforts to overtake real estate in Fox Point. As Brown plans to increase the size of its student body and the University continues to expand, our relationship with surrounding communities must not be ignored. Brown’s responsibility lies in embracing its dual roles — as both an institution responsible for its flawed history and as a facilitator for the study of it.

The Fox Point of the 1950s and 1960s is, nevertheless, gone. The thriving, self-sustaining Cape Verdean community that lived there was removed to make way for the growing University and a new, bustling interstate. But that’s not quite the end of the story. “Our bonds haven’t been broken,” Andrade-Watkins says, regarding the Cape Verdean community today. “We’re going to be Fox Point forever.” She explains to me that even decades after the destruction of the Fox Point Cape Verdean community, when there is a death among the original residents, hundreds of Cape Verdeans still show up to the funeral. There are some bonds, it seems, that even highways cannot break.

Art by George Esselstyn.

Check out the corresponding photo essay here: http://brownpoliticalreview.org/2015/03/media-spotlight-fox-point/