In a run-down Los Angeles neighborhood in late January, a homeless veteran struck up a conversation with Robert McDonald, the newly appointed Secretary of Veterans Affairs (VA). After learning that the veteran had served in the Special Forces, McDonald jovially replied: “Special Forces — what years? I was in Special Forces.” What seemed, at the time, little more than friendly banter between two soldiers quickly became a ringing indictment of the VA.

While McDonald is indeed a West Point graduate and was a soldier for five years, he never served in the Special Forces. For this little lie, captured by CBS News cameras, McDonald’s reputation took a big hit. Days later, he admitted under pressure: “I made a mistake, and I apologize for it.” He insisted that, beginning with his service in the Boy Scouts and up through his role as Secretary, integrity was “one of the foundations of [his] character.” Nevertheless, Chairman of the House Veterans Affairs Committee Rep. Jeff Miller (R-FL) said the events had left him “disappointed” in McDonald, while others, like Rep. Mike Coffman (R-CO), were more ready to forgive and forget: “The secretary’s misstatement was an error, but it doesn’t dim the fact that he served honorably…We should all take him at his word.”

This is but one in a series of gaffes that have cast a shadow of suspicion on the VA Secretary’s office. In February, McDonald stated that 60 workers had been fired as a result of a recent scandal beginning at Phoenix Veterans Affairs Health Care, which revealed the outrageous wait times for veterans trying to receive medical care. Later, McDonald admitted that the true number of workers fired was only eight — although some estimates have put it closer to 20. This exaggeration reflects particularly poorly on McDonald’s record, since he had originally promised to “aggressively” hold staff accountable for their mistakes. The New York Times found that, as Secretary, McDonald “has fired fewer employees than his predecessor did in the year before he resigned.”

During the same week as McDonald’s 60-to-8 blunder, the Secretary made another touchy mistake. While arguing with Rep. Coffman — who had defended McDonald after the Special Forces comments — regarding a VA facility in Colorado, the frustrated Secretary lashed out at Coffman’s credentials, asking: “I’ve run a large company, sir. What have you done?” McDonald was apparently ignorant of Coffman’s record not only as an influential representative, but also as the founder of a property-management firm, the former Secretary of State and State Treasurer of Colorado and as a Marine Corps veteran who served in Iraq.

This recent series of unfortunate events has greatly undermined Secretary McDonald’s goal to rebuild trust in the VA — trust that the institution has lost in the wake of a vicious cycle of scandals, mismanagement and waste. It’s little secret that the VA has gone through a rough patch lately. Scandal after scandal led to the ousting of former Secretary Eric Shinseki and a series of bipartisan initiatives to reinvigorate the federal bureaucracy. Despite these efforts, the VA is still in dire need of even the most basic reforms.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs’ 300,000 employees are responsible for the benefits, medical care and burials of approximately nine million US veterans. The medical system, however, has been heavily criticized, with many veterans’ groups, politicians and media outlets chiding the bureaucracy for its inefficiency and budget woes. Recently, the difficulty in providing timely medical services has placed the VA under a microscope. After discharge, veterans must go through a lengthy process to register for care. They are then means-tested, and wealthier veterans are given lower priority. After all the paperwork is filed and approved, patients are supposed to wait no more than two weeks to see a doctor — but that speedy timeline is far from standard practice. In fact, a report by the VA’s inspector general called the scheduling problems “systemic.”

Problems with the VA are nothing new. In 2008, presidential candidate Barack Obama made a campaign promise to fix the “broken bureaucracy of the VA,” which had been severely troubled for the last decade. A 2001 study found that typical wait times for veterans to obtain medical appointments were two months; a 2003 commission found that more than 230,000 veterans had been waiting more than six months; and in 2007, big bonuses for VA officials sparked public anger in the face of massive backlogs and problematic internal reviews.

Though wait times have been the subject of much scrutiny, they are far from the only issue with veterans’ hospitals. Once veterans finally get treatment, the quality of care is often substandard. In 2009, it was found that 10,000 veterans were potentially exposed to infection as a result of improperly sterilized medical equipment. Thirty-seven had contracted HIV or hepatitis. Similarly, in 2011 a dentist who admitted failing to change his gloves or even wash his hands between patients accidentally gave hepatitis to nine veterans. Adding to the tragic situation, in 2012, 120 VA-managed graves were discovered to be misidentified.

A report issued last year by then-Senator Tom Coburn (R-OK) found that at least 1,000 veteran deaths in the past 10 years may be traced to VA malpractice and delays. The VA, however, officially admits to only 23 delay-related deaths. Coburn also accused the VA of failing to manage its budget. The report reveals that the organization has spent $20 billion since 2001 on projects like office renovations and new call centers that receive only 2.4 daily calls on average. Furthermore, the VA’s construction projects routinely and massively exceed their budgets. The construction of a new $2 billion hospital in Aurora, CO — a project originally capped at $600 million — is just one example. Representative Coffman called the VA’s actions in Aurora “pure incompetence,” and the VA Director of the Office of Construction and Facilities Dennis Milsten described it as a “fiasco.” The VA’s budget has also been strained by gratuitous administrative fees: Even during the current controversies, 78 percent of managers have qualified for bonuses, including former VA Regional Director Michael Moreland. In 2013, Moreland received a $63,000 bonus for instituting policies to prevent infections, despite the fact that an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease at a hospital under his jurisdiction killed six veterans.

The Coburn report found a litany of other problems, including drug dealing, sexual abuse and theft. In one particularly egregious case, a staff member at a Florida VA facility was found selling patients’ personal data to acquire crack cocaine. The practice of overprescribing powerful drugs to patients recently made news when it was discovered that the Tomah Veteran Affairs Medical Center had been excessively handing out opioid painkillers to its patients. In response, Congress scheduled a hearing to further investigate the VA’s painkiller prescription practices. “This is the tip of the iceberg,” Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI) said.

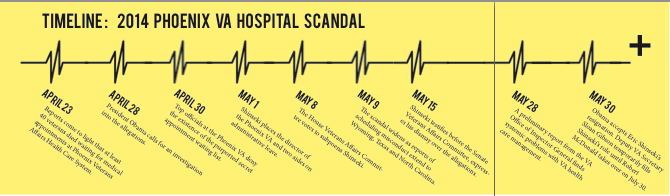

The depth of the VA’s woes was ultimately revealed in 2014 at a hospital in Phoenix, AZ. In April, a review revealed that staff had been keeping an under-the-table list of appointments and claims in order to hide the true length of the hospital’s wait times. Forty veterans had died due to the delays. It was later determined that almost 2,000 more were “at risk of being forgotten or lost” in the hospital’s byzantine system. The same month, the hospital’s director, Sharon Helman, received an $8,495 bonus for her performance.

When the scandal blew up in the press, Obama ordered an investigation of the hospital, even as top VA officials denied the report’s validity and the corroborating claims of whistleblowers at the hospital. After the House Veterans Affairs Committee voted to subpoena then-Secretary Eric Shinseki, a further 69 VA facilities were put under investigation for doctoring their official records.

The ongoing saga is not merely the sum of its scandals, but is also evidence of a colossal failure of leadership. Senior VA officials had been aware of the situation in Phoenix long before the story broke. Susan Bowers, who was responsible for VA establishments across the Southwest, had informed Secretary Shinseki of the problems posed by backlogs as early as 2009, warning that the Phoenix center was set to “implode.” A federal judge even ruled that it was “more likely than not that at least some senior agency leaders were aware, or should have been, of nationwide problems getting veterans scheduled for timely appointments.”

While the former undersecretary for health, Dr. Robert Petzel, confirmed those claims, saying that the VA knew about the wait time issues, Shinseki continued to deny the allegations. Shortly after, Shinseki resigned and Obama appointed McDonald to take over.

I need help,” pleaded Richard Miles, upon entering a VA hospital in February. Miles had a history of post-traumatic stress, anxiety and insomnia. He had violent dreams, had been hospitalized four times for his disorder, had once brought a gun into a hospital intending to commit suicide and had tried to hang himself twice. But when Miles showed up at the VA hospital, he was only given Lorazepam, a sleeping and anxiety medication, and turned away. Miles was later found frozen to death, having ingested a toxic amount of the drug.

Since Miles denied having suicidal desires, the VA doctors were only following procedure when they turned him away. But Miles’ story sheds light on a bigger problem: The system is not properly designed to seriously tackle veterans’ mental health problems. In recent years, the VA’s inability to address mental health needs has been spotlighted by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan — a report even revealed that the number of suicides by US troops have overtaken the number of soldiers’ deaths in Afghanistan. “We’re missing the boat with these most at-risk veterans,” explains Brandon Coleman, who worked on suicide prevention at the Phoenix hospital. “We can’t just hand these guys pills. [That] is not the answer.” Miles’ case — among others — indicates that suicide prevention is not just a problem about access to physical resources, but also about when and how veterans are treated for their mental health issues.

In February, Obama signed a measure to combat veteran suicides. In a rare moment of agreement, the law was passed unanimously in both the House and the Senate. The law will make changes to VA procedures in order to help veterans find resources for mental health care. It will also recruit additional mental health staff for VA establishments, create interactive online resources and provide more time and flexibility to veterans who are seeking care. The new legislation is critical, since some estimates have determined that 22 veterans commit suicide each day. The law is named after Clay Hunt, a Texas Marine who took his own life at age 28 after a long struggle with post-traumatic stress. Tragically, 15 members of his unit also committed suicide after their returns from active duty. “This is an issue that needs to be seared into the forefront of every citizen of this country,” said Jake Wood, a former Marine who served in Afghanistan with Hunt.

In light of these stories — and the many others like them — it is clear that the VA’s approach to mental health has many more flaws than the Clay Hunt legislation alone can fix. Beyond expanding access to medical care and technicians, the VA must also rethink the methods it uses when assigning treatment. As Coleman said, medicine without proper counseling doesn’t go far, and many of the counseling services that the VA does offer use methods that have been noted to actually make depression worse in some patients. Until there is more serious reform to how the VA handles its mental health patients, veteran suicides will continue to plague the country. So although the new legislation is a step in the right direction, it is only a step: The VA still has a long way to go.

The Phoenix scandal essentially tells the same story: implementation of a few constructive policies, but ultimately failure to create comprehensive reform. Nine months after the story first broke, what Obama called a “corrosive culture” at the VA remains. Few new doctors have been hired, bungling supervisors have yet to be replaced and trust between veterans and the system built to protect them is exceedingly rare. In March, Obama talked with hospital managers and staff during a visit to the hospital at the heart of the scandal, where continued delays on reforms suggest that Obama’s old campaign promise may be left in Arizona’s desert dust.

Dr. Sam Foote, a whistleblower from the Phoenix hospital, said that despite the publicity surrounding the VA’s problems, “very little has changed,” and that hiding delays remains a common practice among hospital staff. Even while supporting McDonald and praising those at the VA — whom Obama insists have generally worked hard for change — the president nevertheless conceded that “there is still more work to do.”

While there has been some staff changeover since the Phoenix fiasco, “not a single VA senior executive has been fired for wait time manipulation…[and] efforts to hold employees accountable in Phoenix have been repeatedly botched,” said Rep. Miller. Instead, Helman, the hospital’s director, was relieved for inappropriately accepting gifts. And although 1,100 employees in VA establishments across the country were fired in 2014, VA officials said that none of those decisions were directly related to the scandals. Furthermore, Phoenix hospital’s Chief of Staff Dr. Darren Deering, who denied that delays were a problem to a Senate committee investigating VA fraud, received no punishment and still serves in his same position.

The ineffectiveness of reform is exacerbated by the blowback that whistleblowers have faced. Though they were promised protection after the scandal, whistleblowers like Alabama’s Richard Meuse and Shelia Tremaine have complained that they have been cut out of administrative conversations and excluded from meetings. Whistleblowers’ jobs are supposed to be protected, and though neither has been fired, both feel as if they are now hindered in their ability to effectively perform their jobs. “They’ve cut us out of our responsibilities. They’ve watered down our positions,” said Meuse. Legislation that would expedite policy responses to whistleblowers’ complaints has been drafted in Congress, but it has not passed. Even if it does, it will still be a long time before reporting systemic problems — without personal consequences — will be simple and effective.

Nevertheless, there have been a few constructive steps forward. For example, in a long-overdue move, VA hospitals now allow appointments at night and during weekends, effectively adding another 880,000 visits per year. Additionally, almost 4,000 new physicians, nurses and technicians have been hired — although the agency admits that recruiting is difficult and shortfalls in staffing remain. Overall, though, the total number of visits continues to rise. “They’ve made terrific strides in on-time appointments,” said Dr. Katherine Mitchell, one of the Phoenix whistleblowers. “I know a bureaucracy this size is a slow-moving beast, but I’m cautiously optimistic.”

During Obama’s Phoenix visit, the President also announced a new project: an advisory committee to recommend improvements to the VA, which will include representatives from nonprofits, veterans groups and political officials. Yet not everyone is optimistic. Arizona Sen. John McCain, for example, dismissed the initiative, saying that it serves “more as a photo-op for the president than…a meaningful discussion of the challenges our veterans continue to face in getting the timely health care they have earned and deserve.”

More specific reforms are also in the works. The VA recently announced changes to how they will determine priority for care — net worth will no longer be included as an eligibility factor, and instead, expenses from the past year and gross household income will be factored into the calculations. Veterans also no longer have to update their information year-to-year, as the VA has established a program to automatically receive and update information in collaboration with the Internal Revenue Service. Overall, the change could lower costs for almost 200,000 veterans over five years, although it is expected to cost the VA between $55.5 and $80 million.

Some critics of the reforms worry that the new system for standardizing and digitizing form submissions will make it difficult for older veterans, former servicemen with certain disabilities and those without access to the Internet to register for care. Under the old rules, only a handwritten note was required at the beginning of the enrollment process, and while the new system will improve recordkeeping, it also risks boxing out certain veterans. The VA has claimed that its changes will double the number of claims made on standard forms — but even that figure underscores the current importance of the nonstandardized options for filing claims.

Another long-overdue innovation is the creation of the Veterans Choice Program, or Choice Card, which was implemented in late 2014. The program allows veterans who live far away from VA hospitals to seek subsidized private care elsewhere. The original measure limited availability to veterans who had waited more than 30 days to secure an appointment with a VA doctor or who were living more than 40 miles away from VA establishments.

One of the most critical problems with Choice Card lies in that 40-mile requirement. The distance is measured “as the crow flies,” but that doesn’t take into account the difficulties faced by veterans whose actual drives may be longer than those 40 miles. In recognition of the problems that interpretation has created, 41 Senators and 53 Representatives have signed onto documents supporting alterations in the eligibility requirements for Choice Card, and the House has even scheduled a hearing regarding the 40-mile rule. The failures of the 40-mile requirement eventually became widely known enough — even taking a prime slot on the Daily Show with Jon Stewart — that officials felt pressured to bring about some measure of change. In March, the VA announced it would begin to factor driving time into its calculations.

The program’s chronic underuse demonstrates the importance of the problems with eligibility requirements. Between Choice Card’s introduction in November and March, only 27,000 veterans had taken advantage of the new rules, despite approximately 500,000 veterans being eligible. Though the new regulations are one step towards changing those numbers, the 40-mile rule isn’t the only problematic factor. Underuse is made worse by confusion over most of the eligibility rules and by an abundance of rejections: Many who expected to be cleared for Choice Card have been turned away — almost 80 percent, according to a February survey by Veterans of Foreign Wars, who called the figure “unsettlingly high.”

Pat Baughman, an Air Force veteran, is one such case. Expecting to be allowed to use private care, since he lives 50 miles — or one hour — away from the nearest VA hospital, Baughman requested permission to use Choice Card and to seek closer, private care. But when he talked to officials, they told him that he instead would have to drive three hours to a different VA establishment. Further conversations also led nowhere: When Baughman told officials that the decision did not make sense, a VA hospital two hours away was suggested to him instead.

The rule also only takes into account distance from any VA facility — not necessarily from one equipped to provide the specialized care that the veteran may need. VA officials have said that this loophole cannot be changed internally. Instead, legislation will be required if the eligibility program is to be fixed. Paul Walker, a veteran in Minnesota, experienced the consequences of the requirements’ failure first-hand, when he was told that he did not qualify for Choice Card because of a nearby VA facility, even though it was 50 miles to the nearest one that could provide his cancer treatment. “I don’t get a choice,” Walker said. “I get to die.”

Ultimately, many of the changes that the VA has attempted have led to the same result: a realization that the agency still has very far to go to clean up its own bureaucratic mess. Steps that have already been taken, like Obama’s new advisory committee, the suicide prevention efforts and increased hiring of health care professionals are promising channels for progress. But regulatory loopholes and problematic oversights still need to be resolved for the agency to function with the sort of integrity that McDonald has promised — and so far failed to deliver.

Art by Maria Paz Almenara. Graphics by George Esselstyn.