On October 29, the European Parliament voted on a resolution encouraging member states to offer asylum to Edward Snowden, the former government contractor who leaked classified information about the United States’ NSA surveillance program two years ago. The resolution also officially recognized Snowden as a “human rights defender.” The decision is nonbinding, but it stands as a forceful encouragement for European countries to offer Snowden asylum and protection.

Although the resolution is mostly symbolic, it reflects a massive shift in how government surveillance programs are evaluated by the European public and illuminates the changing face of relations between the United States and Europe. As a greater amount information on these programs has been made accessible, public opposition to the programs has grown. The EU parliament’s vote mirrors this collective change in view.

The altered public opinion shows the radical difference between the current political environment and that which gave rise to the development of these government surveillance programs. In the months following the September 11 attacks, governments around the world revised their conception of national security and constructed far-reaching surveillance programs in response to the pressing fears of future terrorist attacks.

In the United States, efforts to prevent terrorism became the country’s primary foreign policy priority, one that arguably took precedent over the nation’s long commitment to civil liberties. Leaders struggled to devise a response to the attacks and to act in the best interest of protecting the country.

In the past 14 years, although the face of terrorism has evolved, the threat of attacks remains present. The development of international terrorist organizations like ISIL continues to make national security a subject of primary concern for the United States and for countries around the world. Never is this fear more present than it is now, as France is still reeling from the terror attacks that took place within its borders on November 14.

Accordingly, the United States and its European allies continue to grapple with how to best devise an effective framework for protecting their national interests. The American NSA finds its counterparts in Germany’s Bundestag surveillance unit, France’s alleged Frenchelon, and the UK’s GCHQ surveillance unit. What’s more, Snowden’s leaked information exposed that these surveillance organizations have largely worked in tandem with the NSA. Coordination frees governments from domestic limits to surveillance in their own countries by spying on each other and then exchanging information. The NSA in particular is given more extensive leeway regarding intelligence-gathering on other countries and international organizations.

Furthermore, it seems that in recent years, spying and surveillance conducted by Western governments has become more widespread. In October, Germany passed a new data retention law, expanding the ability of Internet and cellular providers to retain data. This past summer, France adopted a hugely controversial law that further enabled the government to pursue invasive surveillance methods, while Austria is in the process of evaluating new surveillance-related policy changes. And the Obama administration – although committed to an overhaul – has recently restarted surveillance initiatives, still navigating its way to a new stance on the issue in the post-Snowden era.

So how does Snowden’s pardon by the EU parliament fit into this international landscape, one in which countries are as committed as ever to pursuing the very programs that Snowden sought to undermine?

First, the decision is undeniably legitimized by the fact that public opinion has been shifting away from support for these types of programs. In the wake of 9/11, national security might have provided enough grounds for the public to support these invasive measures; for many, however, government claims of national security no longer provide a tenable claim.

A Pew Research Center survey from 2014 shows that citizens in countries around the globe overwhelmingly find government surveillance of personal communications “unacceptable,” with 97 percent of Greek respondents, 88 percent of French respondents, 87 percent of German and Spanish respondents, and 70 percent of UK citizens polled holding this view. This public context forms an environment in which the EU parliament has revised its stance to a more forgiving and even appraising position on Snowden and whistleblowers in general.

But discussing the merits or drawbacks of the parliament’s action does not present the full picture; EU members were motivated by more than just public support. There is a strong case to be made that the EU parliament’s pardoning represented a diplomatic rebuke of the United States. By naming him a human rights activist, the EU has decisively challenged the United States and the Obama administration.

There has been no official statement from Obama on the decision, but in a response this summer to an online petition asking to pardon Snowden, the White House made its stance clear, stating “He should come home to the United States and be judged by his peers – not hide behind the cover of an authoritarian regime.” It is evident that the administration’s position is in direct conflict with the EU parliament’s standing; this conflict suggests that the decision was intentionally defiant.

Why challenge the United States? One potential answer is that the EU wants to confront US hegemony, and this decision is part of a larger effort of resisting American power abroad. The chairman of the Workshop of Eurasian Ideas, Grigory Trofimchuk, has supported this interpretation. He argued in an interview with Radio Sputnik, “I think that Europe’s decision – is not simply a formal document, but the intentional act of defiance to Washington that goes against US policy on the Snowden issue…[Europe] gladly seized the opportunity to demonstrate its independence.”

In other words, perhaps more than a statement on surveillance, the EU parliament’s decision was largely an effort to capitalize on an opportunity to “demonstrate its independence.” Siding with Snowden allowed the EU to collectively cement its authority as distinctly separate from the United States’ influence. This interpretation would explain the apparent inconsistency of backing Snowden at a time when they are implementing policies that bolster their own surveillance programs.

Moreover, this challenge comes at a time when the United States has noticeably trailed behind European countries in its efforts to support the flow of refugees from Syria. Given that the United States often takes a prominent and leading role in the mitigation of international crises, it is significant that its presence has been weak in aiding the accommodation of Syrian refugees. Perhaps the EU parliament’s political move is a symbolic provocation, then, a signal to the United States. If the United States won’t step up, then the EU will act independently — its pardon of Snowden a symbolic gesture of that intention.

Ultimately, how this action by the EU parliament will influence US policy remains to be seen. With respect to Snowden, for the immediate future, not much will change practically. According to an interview with his attorney, Snowden will continue to live in Russia on his three-year residency permit and can only hope that the parliament’s decision will provide the impetus needed for European countries to take concrete action and offer him asylum.

We will also observe how the United States responds to this challenge to its authority in the international sphere. It remains to be seen whether the White House will directly confront the EU on this question of surveillance or whether it will act to reassert American authority on another front. In the wake of the major ISIL terror attacks worldwide, there is abundant opportunity for the United States to make moves on the world stage; Obama’s choices on policy and action will demonstrate to what extent the White House chooses to demonstrate its leadership.

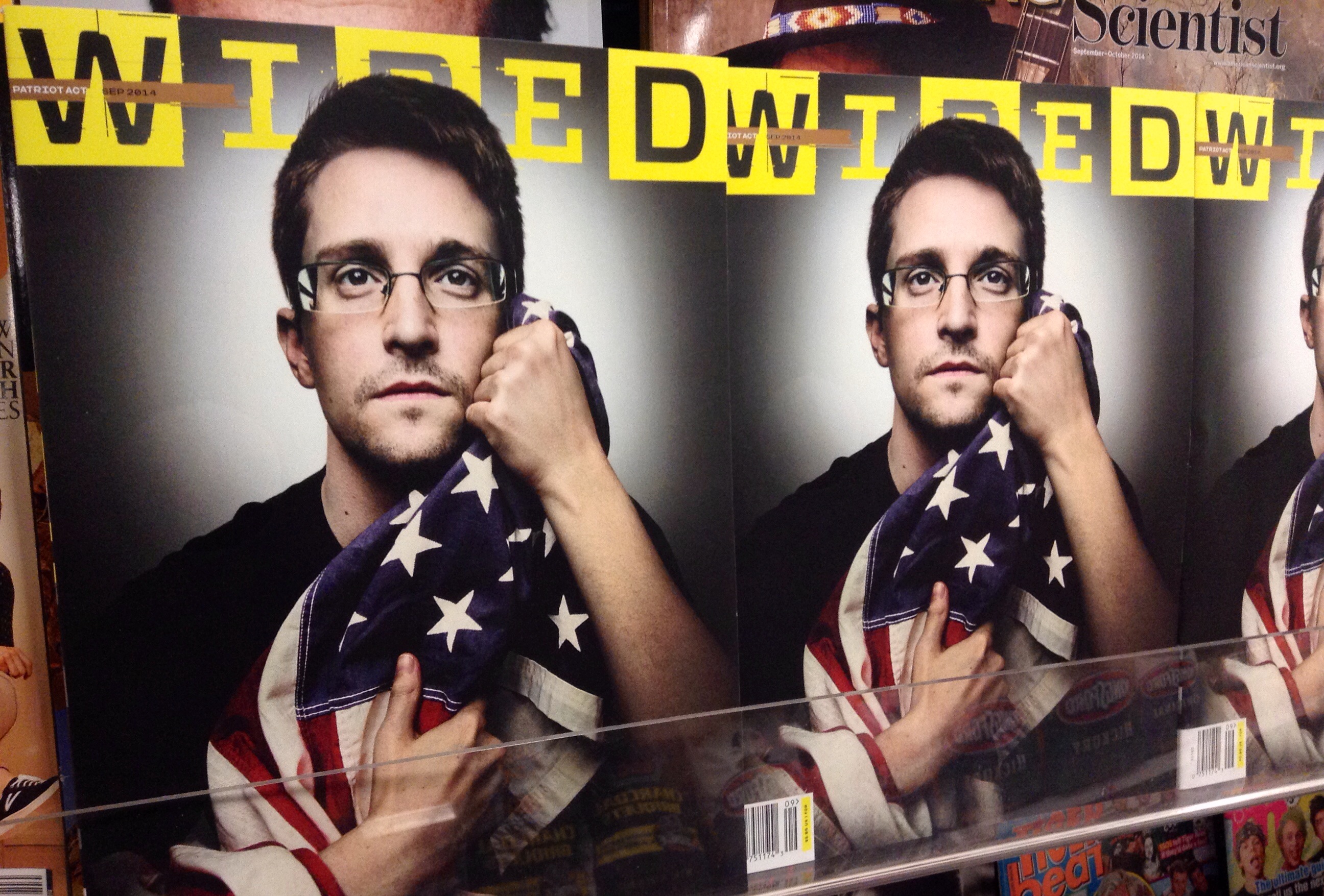

Photo: Mike Mozart