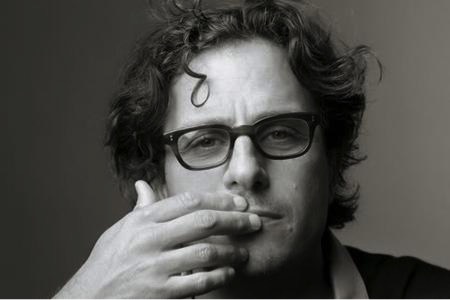

Davis Guggenheim ‘86 is a documentary filmmaker. He is best known for “An Inconvenient Truth,” “It Might Get Loud,” and “Waiting for ‘Superman.’” Guggenheim’s latest film, “He Named Me Malala,” was released this year and chronicles the life of Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai, the youngest-ever winner of the Nobel Prize.

Why film? Why documentaries?

When I was graduating Brown in 1986, I remember thinking that there was no future in documentaries. My father made documentaries, and I felt like all the big deal filmmakers were set, they were institutionalized, and there was no room for me. I was really wrong because documentaries have had a huge explosion in the last 10 to 15 years. So I’m glad I was wrong. I also wanted to make it on my own and not do what my father did. My father made a lot of great social justice documentaries. So I drove to Los Angeles after Brown, and I tried to make it as a big Hollywood director. I worked in Hollywood for about 10 to 15 years and was about to direct my big break — this movie called “Training Day,” which was going to be made from Warner Brothers. And I got fired from it. It was devastating, and I was depressed. I kind of sat at home for six months, and then finally I bought an old camera and I decided to make a movie about people I liked… I ended up following these teachers, people I knew who were first-year teachers for Teach for America who were going into the more troubled neighborhoods in Los Angeles. I found myself working in these schools and was feeling invigorated by these stories — sometimes angry, but sometimes excited and hopeful — and I started making documentaries. So I grew up around documentaries and sort of rediscovered it my way. And now, I still direct commercials and television a little bit. But I love documentaries.

There are endless issues out there that are good stories and are also worthy of attention. How do you go about choosing the subjects of your documentaries?

They have to be stories that I care about — because if you just do it because you should, that will come through. If you’re doing it because someone else cares about it or because it’s an assignment, it’ll come through. If you care about it, it’ll come through. If you’re angry, it’ll come through. If you’re inspired, it’ll come through. If you love the characters, it’ll come through.

This journalistic principle of being dispassionate — I reject that premise. I want to be moved, one way or the other. So that’s important. There’s much less burden on documentaries to be dispassionate. I think journalists face that a lot more…I think documentaries are shifting away from journalism for good and for bad. It’s not always good. As long as the audience knows where you’re coming from and what your agenda is, and if you have an agenda, then it’s okay. When people watched “An Inconvenient Truth,” they knew that climate change was real. So we didn’t feel obligated to say that on the other hand people don’t believe this. The audience knew that we were making our case. As long as they knew that we knew that they knew, it’s all okay.

“Waiting for ‘Superman’” received a lot of critical feedback due to the way it portrays charter schools. Has your view of charter schools evolved since you made this film? What did you learn from that experience?

With “An Inconvenient Truth,” it was a movie that was embraced — at least by people I knew and my world and the newspapers I read. People were saying, “this is good, this is exciting, this is important.” Not everybody agreed with it. But with “Waiting for ‘Superman,’” it really divided my friends and colleagues. Because on one hand it was for public schools, and on the other hand it criticized unions. I come from a very liberal, progressive group of people. Half of the people just couldn’t get past the idea of criticizing unions. People were confused. And I was criticized a lot more. I wish I could say it doesn’t bother me, but it really bothers me.

Did you find anything surprising in the process of filming your latest documentary “He Named Me Malala”?

The revelation for me is that Malala is an ordinary girl. You think she’s this superhuman, a person that my daughter could never be, or that you could never be. But what I realized is that she is from a small town and a remote part of the world. What makes her extraordinary is that she took an extraordinary step. So when you’re with her at her house, she’s teasing her brothers, Googling her favorite sports stars, and worried about her homework. Just the fact that she’s an ordinary girl was a revelation. It doesn’t seem like it was much of a political revelation, but it was to me.

You did a short documentary on behalf of the Obama campaign in 2012. What are your thoughts on the current political situation in the United States? Are you worried that it has been characterized by partisanship and a polarizing set of presidential contenders?

I’m not very excited right now about the presidential race. Really urgent issues like climate change aren’t talked about — or are barely talked about — and that is disturbing. I think it’s easy to blame the candidates, but we also have to blame the news media and ourselves for watching the news media. If we stopped watching, if we demanded more thoughtful coverage, they would give it to us. They follow the ratings. It’s not a great time for politics. I’m waiting to be inspired, but it hasn’t happened yet.