In the late 1980s, Dr. Timothy Quill ignited a national debate when he published an article describing his role in administering a lethal dose of medicine at a patient’s request. Quill’s case ultimately averted indictment in the presence of a grand jury. But years later, the conviction of Dr. Jack Kevorkian, a physician who openly assisted in the deaths of over 40 of his patients, cemented national public opinion against physician-assisted death. Over the past few months, however, debate over the practice has started once again. In October, California Governor Jerry Brown signed into law the End of Life Option Act, following in the footsteps of four other states: Oregon, Vermont, Montana, and Washington. Modeled after Oregon’s legislative package, the End of Life Option Act gives terminally ill patients with six months or fewer to live the option of receiving a lethal dose of medicine under the care of a physician.

Despite its recent resurrection in legislatures, the right to die has long been a morally contentious issue. Opponents view physician-assisted death as a threat to life as well as a violation of the Hippocratic Oath. Proponents argue for patient autonomy in the final moments of life and the notion of death with dignity. But the justification for right-to-die legislation goes beyond a moral position: The lack of right-to-die laws in the majority of the United States has engendered dangerous, unregulated medical practices in an underground system of physician-assisted death. While California’s success may suggest progress for this political and public health movement, there’s still work to be done in the rest of the nation.

Because certain terminal patients will often pursue death regardless of its legality, they often end up taking hazardous end-of-life measures. In some cases, doctors or nurses may give patients or loved ones lethal doses of painkillers, as Pennsylvania nurse Barbara Mancini did with her 93-year-old father, who was in hospice care. Other patients take matters into their own hands. In 2014, John Rehm, a Maryland resident with Parkinson’s disease, asked his physician to illegally prescribe him lethal medicine. When his physician refused, Rehm starved himself to death over a period of 10 days.

While stories like Rehm’s are usually buried by the media, feelings of helplessness and depression among terminally ill patients are pervasive: Nearly 50 percent of suicides by terminally ill patients stem from untreated depression. In states where physician-assisted death is regulated, doctors are required to direct patients to other sources of end-of-life care and work with them through their decision. In an unregulated environment, essential practices like recommending other sources of care, monitoring for underlying mental health issues, and mandating physician reporting are overlooked. Physicians who opt to perform assisted deaths do so with no accountability, leaving any possible abuses of the system undetected.

Even in states where physician-assisted deaths are protected by law, lack of proper safeguard measures can lead to the same results as unregulated practices. Montana protects physicians who administer the drugs, yet provides few guidelines about the process to patients and doctors. Unlike in Oregon, Vermont, Washington, and now California, Montana’s law does not require physicians to recommend other sources of end-of-life care or the presence of witnesses. The failure to include those protections allows for potential misuse or abuse of the law, whether by a family member with ulterior financial motives or a patient who is unsure of their final options.

Oregon has found greater success with its right-to-die legislation, which has challenged critical notions of physician-assisted death and highlighted the importance of a regulated system. Oregon’s regulations were the first of their kind in the United States and set the foundation for legislation in California, Vermont, and Washington. In all four states, the core of the legislation is focused on precautionary measures to prevent abuses of the bill. Some provisions of the bill include requiring the approval of two physicians; appealing to witnesses who have no familial, legal, or financial ties to the patient; monitoring for underlying psychological conditions; and requiring the patient to file two requests with a 15-day waiting period in between.

Some argue that legalization increases the use of physician-assisted death provisions and takes the focus away from end-of-life care. But Oregon’s law, which was enacted in 1994, has had a limited impact on patients in hospice care and no negative effects on palliative care. In fact, Oregon currently has one of the highest rates of hospice referral in the country, and palliative care within the state has only improved since the establishment of the law. Fewer than 80 patients a year obtain lethal prescriptions, and 39 percent ultimately don’t use them. In fact, physicians in Oregon reject five out of six requests for the medication, instead referring the patients to alternative options — a result of the tight regulations in place.

Today, as 10 more state legislatures grapple with right-to-die legislation, proponents must highlight not only the moral arguments surrounding a patient’s rights, but also the pragmatic ones. Patients can always choose passive death by rejecting treatment that might otherwise have improved the quality of their last weeks of life. As cases like Rehm’s show, the inability to openly seek life-ending treatment drives terminal patients to take desperate measures that may include resorting to an unregulated and underground medical market. Instead, terminal patients should have open and legal access to physician-administered fatal prescription drugs. Without these legal provisions and proper regulation, underground medical practices will continue, and terminal patients seeking to end their lives in a dignified manner will face grave and unnecessary burdens on the fulfilment of their final wishes.

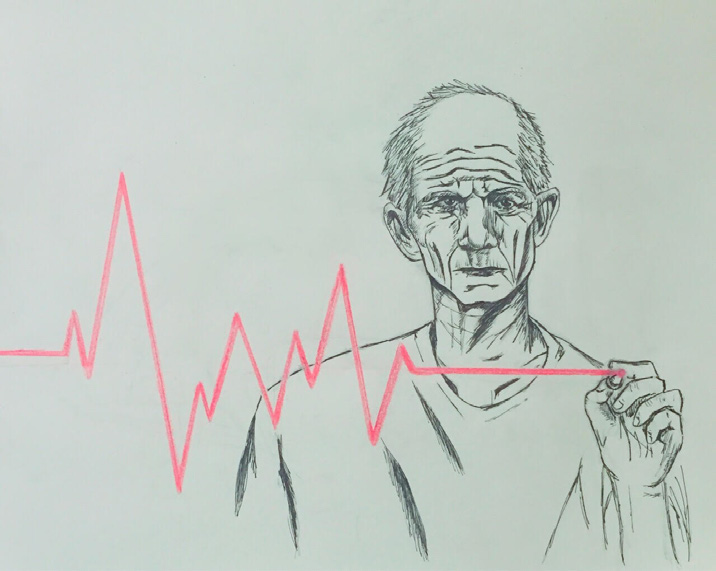

Art by Michelle Ng