Long before 31 governors declared that their states would refuse to accept Syrian refugees, some local pockets in the United States had already been calling for a halt in refugee resettlement for years. In 2011, for example, Tennessee passed the Refugee Absorptive Capacity Act, which allowed local governments to request a moratorium on refugee resettlement in their communities. That same year, Mayor Ted Gatsas of Manchester, New Hampshire personally asked the State Department to temporarily halt resettlements in his city. Officials pushed for similar moratoriums in Detroit, Michigan and Fort Wayne, Indiana. However, these early protests against refugee resettlement were fundamentally different from today’s calls for a ban on Syrian refugees. They were not primarily based on xenophobic fears of terrorism, and they did not target a specific nationality of refugees. Instead, localities were concerned about their capacity to host refugees. Cities and towns were complaining that they lacked the space and resources – available affordable housing, a healthy job market for low-skill labor, welfare program funding, etc. – necessary to help refugees support immigrants and help them integrate into the community.

The refugee resettlement program was formally created in the Refugee Act of 1980, with the original intention of helping refugees fleeing communism, mainly from Cuba and Southeast Asia. Since then, the program has resettled millions of refugees from a variety of areas experiencing conflict, making it one of the largest such programs of any country and one of the United States’ proudest humanitarian initiatives. However, the program has been struggling to coordinate resettlement with local host communities; the pushback from local leaders in Tennessee, Manchester, Detroit, and Fort Wayne reveals as much. In addition to problems with limited local capacity, the refugee resettlement program is also challenged by limited data on long-term refugee health, employment, and overall self-sustainability. Many refugees face setbacks such as limited English proficiency and trauma-related mental health issues, which when paired with limited and fleeting financial assistance from resettlement agencies (the resettlement program emphasizes quick self-sufficiency), can cause many refugees to slip through the cracks. The exact percentage of such refugees is unknown. Since the Obama administration recently announced that the United States would expand the number of accepted refugees from 70,000 per year to 85,000 in 2016 and 100,000 in 2017, the problems within the resettlement program will only continue to grow in number and severity.

Some communities are particularly overburdened due to a phenomenon called secondary migration, when refugees move to a different location after initial resettlement. The State Department tries to spread refugees across the country, but resettlement agencies only provide assistance finding housing, employment, and services for the first 30 to 90 days, and after that support dries up many refugees move to already established refugee communities – often based on common religious, ethnic, or national characteristics – in other cities to be with family and friends. As such, certain towns and cities are frequently overwhelmed with many more refugees than were anticipated.

However, the claims that communities are overburdened with refugees are difficult to back up with data. This is partly due to the fact that the program fails to adequately track secondary migration, making the precise number of refugees living in a community difficult to assess. The Office of Refugee Resettlement did commission a report on secondary migration in 2009 to address this issue, but the report was never released. The author of the report has since commented, “There was a growing interest in learning more about what was happening related to secondary refugee migration…Many communities hadn’t necessarily known that these newcomers were coming and were not always prepared for them.” Other than this statement, however, there is little official information on the extent of secondary migration.

However, some capacity claims from local leaders have conflicted with whatever scarce data exists. For example, in 2014, Springfield, Massachusetts mayor Dominic Sarno asked to halt refugee resettlement in his city because he claimed refugees were dependent on city programs to survive. Interestingly, the state of Massachusetts is the third best state for refugee employment, with 73 percent of refugees employed. Admittedly, the city-level data for Springfield may be different than state-wide data, but if refugees in Massachusetts’s third-largest city were as dependent on the city as Mayor Sarno claimed, that would certainly bring the average much lower than the relatively successful 73 percent state-wide employment rate. So, why would a local leader make a statement that conflicts with some of the only data available?

The reality is that some of the backlash against refugees is driven by xenophobic fears. For instance, in 2012 in Lewiston, Maine, mayor Robert Macdonald openly said to refugees, “You [immigrants] come here, you come and you accept our culture and you leave your culture at the door.” While most statements against refugee resettlement are perhaps not as outwardly anti-immigrant as much of today’s opposition to Syrian refugees, illegitimate claims of “reaching capacity” can sometimes be veiled ways of making the same point. As another example, returning to Springfield, Mayor Sarno supplemented his request to halt resettlement in his city by suggesting that “warm weather” refugees become dependent because of the cold climate of northern cities like Springfield.

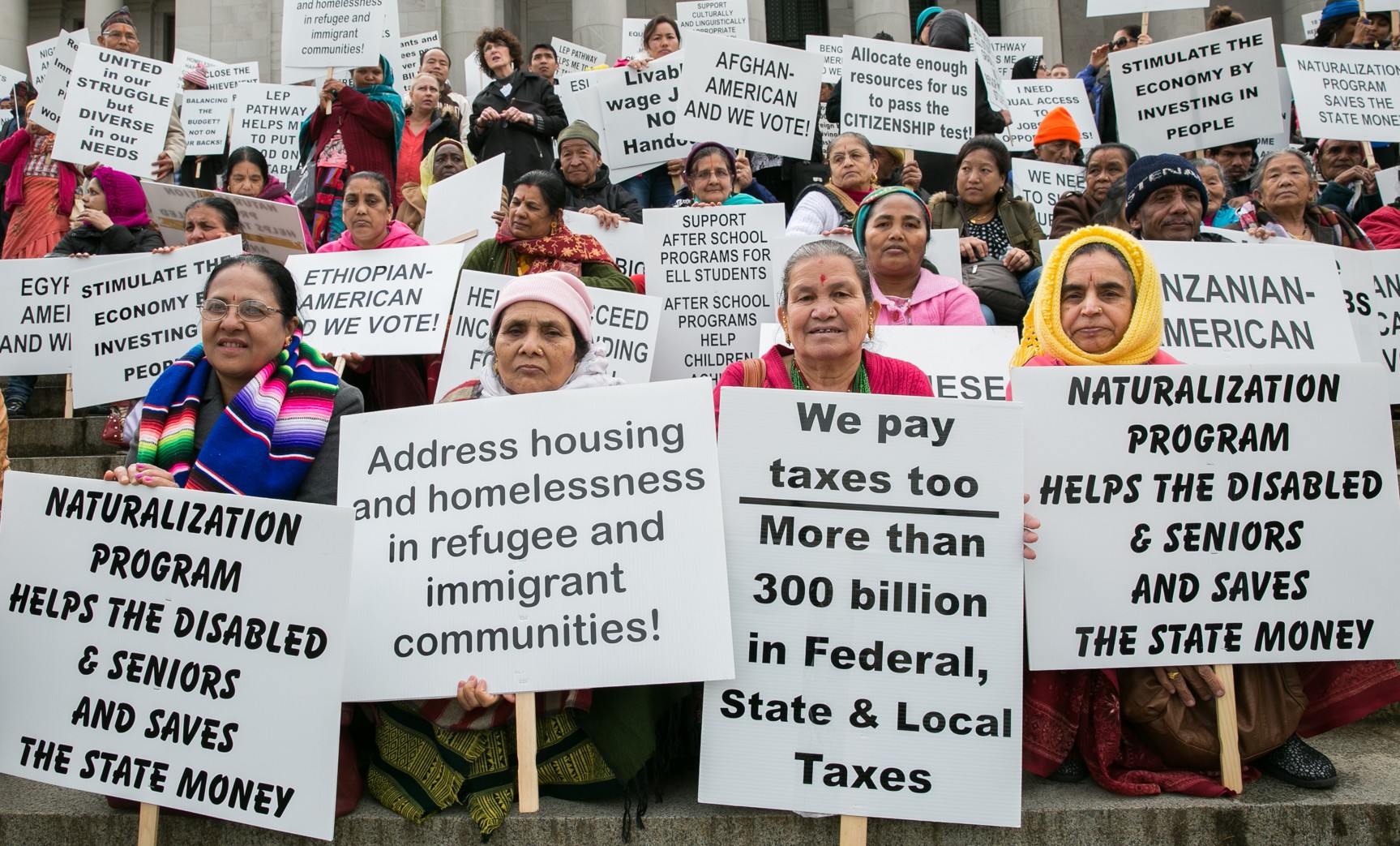

The notion that refugees are simply dependents is far from true; local leaders often fail to acknowledge the benefits that refugee communities bring to American cities. One study out of Cleveland, Ohio found that refugees in the greater Cleveland area generated $48 million in economic activity and $2.7 million in tax revenue in 2012 alone. The study also noted that over time, refugees save up money and some even start their own businesses. Additionally, refugees can bring diverse perspectives to homogenous communities, helping to share cross-cultural understanding with the local residents. As noted by Robert Marmor, head of the resettlement agency in Springfield, “It is unfortunate that 5 percent of refugees who struggle are the focus and not the 95 percent who are really making it.”

While Marmor is right to point out the productive potential of most refugees, many still struggle to make ends meet under the current program. A report from the Journal on Migration and Human Society emphasized that the United States refugee resettlement program was poorly funded and ill-suited to meet the needs of the increasingly diverse refugee population in the United States. The federal government currently provides $850 per refugee to help resettlement agencies receive and place the refugees, but this only covers about 39 percent of the necessary cost to fulfill the requirements in resettlement contracts, according to a 2008 report by the resettlement agency Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services. Furthermore, the program’s emphasis on self-sufficiency is often unrealistic for refugees with difficult backgrounds. Many refugees lack any education and the majority – around 60 percent – do not speak English. Despite this, the program discourages refugees from pursuing continued education because of its focus on immediate self-sufficiency and because of the limited financial support provided to resettlement agencies. Instead the resettlement program encourages refugees to find low-skill jobs to support themselves in the short term. This expectation is especially unrealistic for refugees who come from professional backgrounds but lack the certification to continue their profession in the United States.

Again, the data on refugees is limited, so it is difficult to know exactly what the reality of each refugee’s experience is, aside from anecdotal evidence, or how it varies among host cities across the country. One bill in Congress, the Domestic Refugee Resettlement Reform and Modernization Act, sponsored by Senator Debbie Stabenow of Michigan, has aimed to address this problem for several years, but it has repeatedly failed to pass. The bill has provisions that address most all of the aforementioned challenges with the program: It extends refugee services to secondary migrants and increases efforts to track secondary migration, and it expands data collection requirements so that the program can better understand aspects like refugee employment, health, and housing. A 2011 version of the bill also required the federal government to assess the effectiveness of refugee resettlement and program emphasis on self-sufficiency, and it revised the funding formula for federal program aid in order to make sure communities receive adequate financial assistance to support refugee populations. The passage of this bill, even the watered down current version, into law would be a major step towards addressing the many issues that create tensions between refugees and local communities. Yet, with each passing term it fails to gain enough political support, and the increased anti-immigrant rhetoric throughout the country certainly has not helped.

To overcome the ignorance and veiled racism behind opposition to the program, Americans must better understand the realities of the refugee resettlement program and the families that it supports. After all, refugee resettlement is a crucial humanitarian program, and in taking in these refugees we have a responsibility to make it a fully functional process. As the number of refugees being accepted into the country increases, the resettlement program must be prepared to address the challenges it currently faces or else those issues will only be exacerbated. Decent work is already being done by some committed members of Congress, but, in order to get any reform passed, the American people must be aware and supportive of the issue. Only then can refugees truly escape poverty and persecution, not just from abroad but also within the United States.