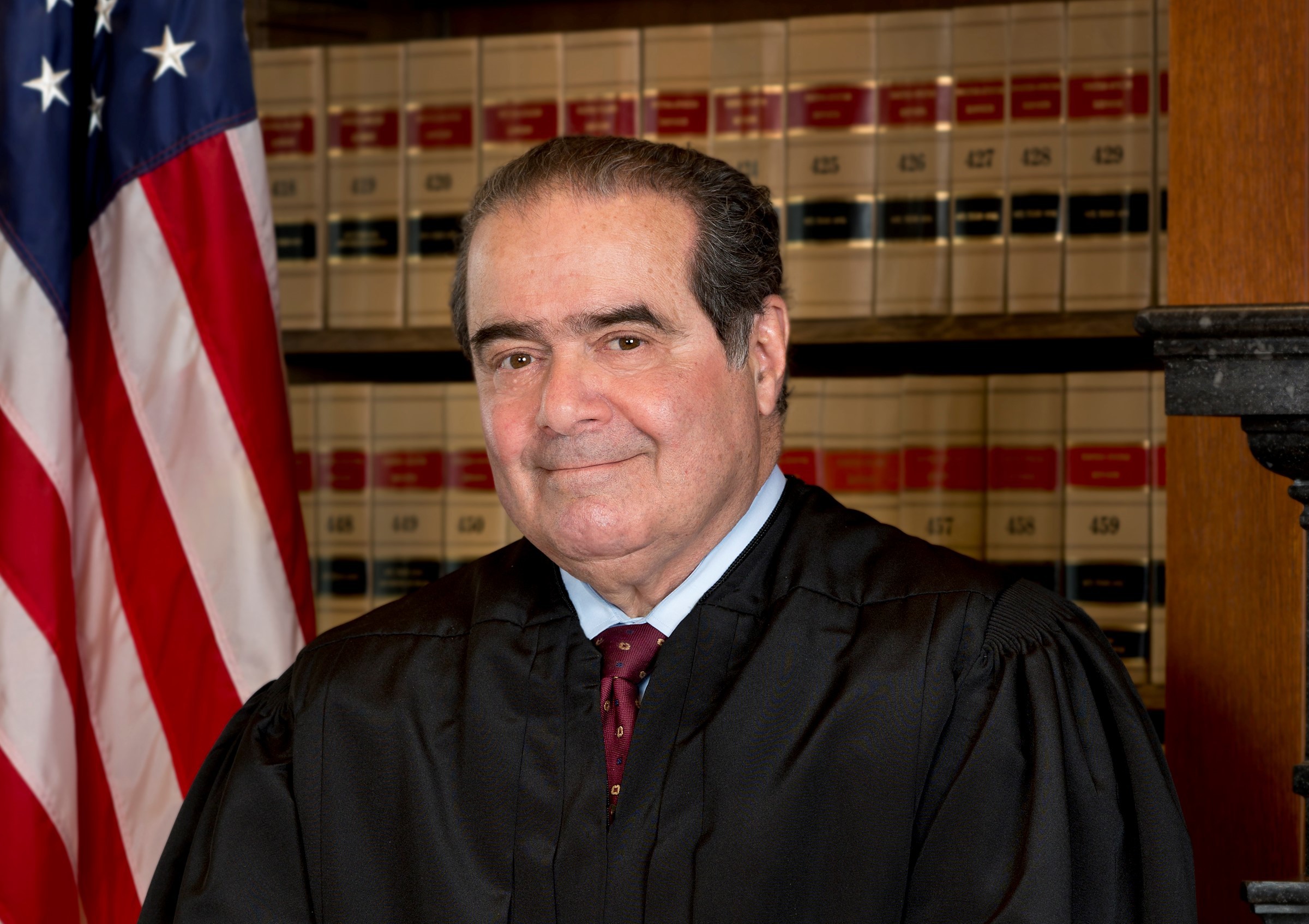

On February 13, 2016, the United States legal realm lost an influential and revered icon. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s unexpected passing has already generated an outpouring of eulogies and sent shockwaves through the US political system. His absence on the bench now leaves a gaping hole in the court, one that is unlikely to be filled by anyone with as piercing a tongue or as sharp a mind. Unlike many other justices, who are relatively unknown to the American people, Scalia was a towering figure, one whose legacy is imprinted on modern American jurisprudence.

But that legacy is often misremembered. Regularly touted as a conservative (or arch-conservative) by the media, Scalia cannot be pinned down so easily. Although he held conservative views as a private individual, it is an insult to Scalia as a justice to insinuate that his decisions were exclusively the result of partisan bias. Instead, Scalia’s mode of constitutional interpretation – often called originalism or textualism – adhered to the original meaning of the Constitution, that which was embedded in the words at the time they were written. He helped found this school of thought, and thanks to his efforts, once-disregarded legal theories now have a prominent place in the academy.

Admittedly, Scalia’s brand of textualism often led him to vote in line with the court’s more conservative members. This makes sense; the framers set up a government of limited powers, and today’s conservative movement mostly aligns itself with small government ideology. For example, consider Scalia’s majority opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller. In this landmark case the court affirmed an individual’s right to own a gun for self-defense. Rather than rely on arguments about the virtues of gun ownership or free market liberties, Scalia’s opinion rested on the 18th century definition of militia and the placement of the prefatory clause in the Second Amendment. His textualism justified a popular Republican position, but it was not a paean to the NRA. Instead, it was a carefully constructed argument of definitions, syntactical structure, and contextual history.

To see how Scalia’s jurisprudence was more than just partisanship, it is instructive to examine the array of cases in which his opinions did not have a conservative bent. For example, he supplied the crucial fifth vote in Texas v. Johnson, joining the more liberal wing of the Court in protecting flag burning under the First Amendment. Nowhere in the text of the amendment did it say that certain symbols deemed popularly or patriotically important were exempt from freedom of speech protections. He also vigorously dissented from the court’s conservative wing in Maryland v. King, rejecting the idea that the Fourth Amendment permitted DNA swabs without a warrant. To Scalia, and consistent with the text of the amendment, the Fourth Amendment’s ban on searches without probable cause was a categorical provision, not one that varied depending on the severity of the alleged crime.

Although it is clear from some of Scalia’s decisions that he was more than just a conservative, current Republican leaders were quick to posthumously attach themselves to his legacy. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell issued a statement lauding Scalia’s commitment to originalism. McConnell also asserted that “the American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court Justice” and pledged to block any nominee President Obama put forward. Under the most generous interpretation of his motives, McConnell was making a thinly veiled plea to respect Scalia’s penchant for deferring to democracy. But it is dubious that Scalia would have approved of such tactics.

The procedure for appointing officials is clearly spelled out in Article 2, Section 2 of the Constitution; the document reads, “[The President] shall nominate, and, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint… Judges of the supreme Court.” Hence it is evident that President Obama is allowed to and has the responsibility to put forward a nominee, even in an election year. This does not, however, purport that Congress has to confirm that nominee. The discretionary latitude encompassed within “advice and consent” is not constrained by the text. An important distinction must then be drawn: To insinuate that President Obama should not even select a nominee is ludicrous, but it is within the textual bounds of the Senate’s jurisdiction to refuse to confirm whomever the President names.

Since it is within their authority, McConnell and his band of obstructionist Republicans are likely to push the Senate to continue delaying its Constitutional duties. At this, Scalia would be affronted. Trying to get inside someone’s mind – especially when that mind is as intricate as Scalia’s – is always tricky business, but luckily his own words and those of the Constitution give us clues as to how he would have thought. On an intellectual level, Scalia was more concerned with legal acumen than ideology, and would weight having a ninth member on the bench more highly than stalling until a more conservative nominee was up for a vote in the Senate.

To see as much, consider Scalia’s reaction when a Supreme Court vacancy opened up in 2009. At a White House dinner, Scalia frankly stated to then-Obama advisor David Axelrod that, “I have no illusions that your man will send us someone of my orientation, but I hope he sends us someone smart.” Scalia went on to recommend Elena Kagan specifically – despite the fact that her views sharply diverged from his own. Although Sonia Sotomayor ultimately got the nod, Kagan was appointed to the court just a few years later. So while Justice Scalia would acknowledge the Senate’s responsibility to deliberate carefully, he would certainly prefer the deliberations to be over intellectual merit than political rancor. After all, this was a man who publicly wrote that whether a potential justice “[reflects] the policy views of a particular constituency is not (or should not be) relevant” in the selection process.

While it is true that Supreme Court nominations are often politicized, the high-profile political fight brewing over the impending confirmation process looks to be particularly egregious. By squabbling over the timing and personage of the next appointee, both Republicans and Democrats in Congress are bringing the court to the forefront of election year discussions. Yet Scalia notoriously disliked judicial activism (his searing, quotable dissent in Obergefell v. Hodges is strong evidence for that point), and he enormously respected the democratic process. Pursuant to this idea, he envisioned the court playing a limited role in American electoral matters and their outcomes, not being thrown into the middle of a brutal campaign season.

Of course, it is only fair that potential members of the highest court in the land are intensely scrutinized before assuming their exalted seats on the bench. Senators have good reason to make their consent hard to earn, so long as it is derived from the qualifications of the appointee, not whether he or she is “on their side” politically. Yet the current Senate’s stated refusal to consider any nominee put forward by the President steps clearly over the line of reasonable vetting and falls squarely within the bounds of petty obstructionism. As a result, the bench will be understaffed, paralyzed, and outwardly political, a reality Scalia would have despised. It violates his wish of keeping judicial and democratic decision-making reasonably separated.

If there is anything to be learned from the hoopla that followed Scalia’s death, it is the danger of reducing Supreme Court Justices to unsophisticated caricatures of political ideology. Branding Justices as conservative or liberal does a disservice to the nuanced job the members of the court have in interpreting our incredibly complex Constitution. Scalia dedicated his career to the technicality and intricacy of Constitutional law; he would have appreciated an honest, constructive discourse about how to fill his vacancy, even if that meant his personal conservatism did not come out on top. To really honor Justice Scalia’s legacy, Congress and the country should shift the debate surrounding his replacement from one about scoring political points to one centering intellectual rigor and legal consistency.