In the early 1930s, the rural Tennessee Valley region experienced a crisis extreme by even Depression-era standards: Malaria was running rampant, per capita income was 44 percent of the national average, constant flooding made living in the region difficult, and only 3 out of every 100 farms had electricity. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, believing the public sector should mitigate even the direst of circumstances, signed the Tennessee Valley Authority Act into law as part of the New Deal, creating the publicly-owned corporation known as the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). This corporation revitalized the region by providing cheap hydroelectric power, flood and navigation control, and programs to improve regional farming practices. Despite the corporation’s widespread success, critics take issue with the TVA: Private utility companies see it as unfair competition, conservative politicians see it as government overreach or even socialism, and environmental groups rail against its historical record of safety and environmental problems. While many of these concerns have merit, recent work to tackle some of the TVA’s lingering issues has already seen limited success. With the right set of reforms and modernization efforts, the TVA should remain under public control and, in an era of privatization on all fronts, set a precedent for the propriety of state-owned enterprises in the modern economy.

Despite its presence in US history books, the TVA’s existence and continued public ownership remains contentious to this day. In 2015, the Obama Administration proposed the sale of the TVA, citing the Authority’s $26 billion debt. However, unless agency debt surpasses $30 billion, the federal debt remains unaffected. In defense of privatization, Obama has argued that the TVA has “achieved [its] original objectives” and therefore should move into private hands. Although the Obama Administration decided that the TVA does have a role as a public corporation and retracted the proposal, the idea still has political traction.

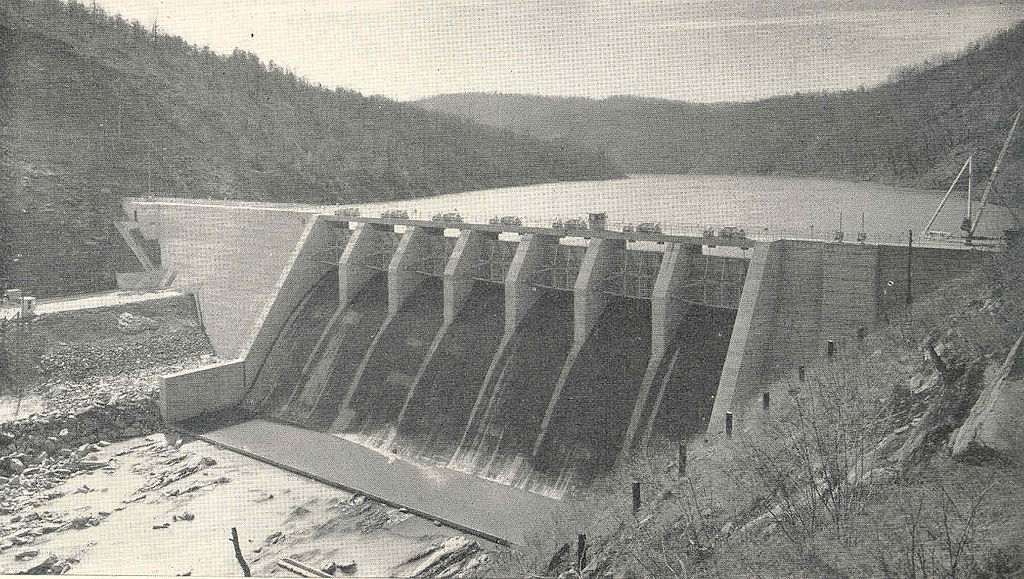

Arguably the most important case to be made for the TVA to remain public is the coordination between the Authority’s power functions, like hydroelectric power and nonpower functions, like river quality and land management. Under a privatized system, the coordination between the TVA’s functions would be in grave danger. Take, for example, one of the backbones of the TVA: the humble river dam. The TVA uses dams for both hydroelectric power generation and flood control. While the Authority could feasibly outsource hydroelectric power to the private sector, a private company would likely ignore flood control without a profit incentive. Thus, if the government privatized the TVA, a private company would assume the role of hydroelectric power generation while a public entity would use the same dams for flood control. Many experts note that this arrangement would be inefficient, ultimately providing less power and less flood protection.

In fact, the TVA integrates its power generation entities across several nonpower functions, most of which don’t generate revenue. These include its river dam system, land management programs, and successful economic development initiatives. Moreover, the public operation of the TVA allows revenue sharing, meaning that money made from selling electricity can be used to fund other functions of the Authority. In a privatized system, federal and state governments would have to find new revenue sources to fund these programs, meaning either tax hikes, broad budget cuts, or significantly decreased funding for nonpower programs. As a study from financial advisory group Lazard Freres reports, “It is unclear how TVA’s nonpower mission and activities would logically fit within a divested TVA structure — any reductions in the scope of the nonpower mission and activities could potentially have a negative impact on the region.”

It is key not to underestimate this “negative impact” on the region, considering some of the success stories that have come from the TVA’s programs since its inception — among them, economic development. This component of the TVA operates a number of programs that recruit and attract businesses and investment to the region through tax credits, site selection services, technical assistance, and training, often partnering with its power component to achieve this. These programs have been highly successful, bringing 224 businesses and an expected 76,000 jobs to the area in 2015.

Over the years, critics have argued that if the TVA were to be privatized, it would be run more efficiently, consequently causing energy prices to decline. While it’s important to concede that mismanagement has, in the past, caused increased prices, analysis has shown that turning the TVA over to private ownership would hurt, not help, this problem. The aforementioned Lazard Freres study predicted that if the TVA were turned over to private utility companies, electricity costs would rise by an average of 13 percent. Instead, the TVA can keep electricity rates cheaper through public ownership by using reliable low-interest government-backed bonds to assume debt. This structure allows the agency to operate on a much higher debt-to-capital ratio than private utilities, permitting the Authority to charge less. Furthermore, the simple process of transitioning from a public electricity system — which is already quite complex — to a private one would be extremely costly and complicated by itself. Through increased uncertainty and price volatility in the system, privatization would squeeze many families’ budgets.

Of course, the Authority certainly isn’t without flaws — fiscal problems and environmental concerns continue to plague the TVA. Even the TVA is aware of this and has actively taken steps to mitigate these concerns and modernize itself. For one, the TVA has started to clean up its financial act. In the 1990s, the enterprise took steps that significantly reduced operating costs and helped stabilize the TVA’s debt. Notable reforms included terminating operations of aging, inefficient coal and nuclear plants, in addition to workforce reductions. More recently, current TVA President Bill Johnson has reduced staffing levels to just over 20 percent of their levels 35 years ago and made significant cuts in operating costs, all to improve the agency’s financial outlook and generate political support. The Obama Administration cited the agency’s ability to keep its debt under control as one of the primary reasons it decided against privatization.

To continue on the path of financial viability, the TVA will need to address its growing pension problem, currently at a $6 billion shortfall. This might prove to be difficult, given the stark objections labor unions representing TVA employees have had to Johnson’s recently proposed reforms. Another avenue that may help the fiscal outlook and mitigate the unions’ objections would be to reduce executive pay. With a net salary of $6.4 million, Johnson is the highest-paid federal employee in the US. Other executives have a net salary just over $2 million. Lowering these salaries across the board may fill some gaps in the Authority’s balance sheet and make unions more willing to negotiate their pension terms.

Furthermore, while environmentalists over the years have critiqued various aspects of the TVA, the corporation has made huge strides toward cutting carbon emissions and prioritizing sustainability. For example, the agency has increased its share of power generation coming from low and noncarbon sources and invested in emissions-control equipment to cut carbon pollution from power plants. As a result, between 2005 and 2014, the Authority reduced its carbon emissions by 32 percent. Recently, the agency has committed to increasing investments in renewable energy sources other than hydroelectric power, such as biomass, solar, and wind. The agency has also announced that it will close 18 of its 59 coal-fired power generators by 2017 and has invested in scrubbers for many of its remaining ones to reduce smog emissions and other forms of air pollution. These environmental improvements are well-timed, as a projected decrease in demand for electricity in the region will also reduce the cost for consumers. By satisfying these critiques and implementing innovative reforms, the TVA is proving its ability to adapt and its potential to run well into the next century.

The TVA’s successes — and the need for it to stay public in order to work best — serve as an important case study for when state-owned enterprises are still appropriate. To remain competitive, governments often must reevaluate functions they can outsource to the private sector. However, policymakers would be well-advised to look to the Tennessee Valley Authority as a paradigm of where government ownership proves to be an enhancement. Otherwise, the agency’s goals be damned.

On Brown U treatise 3-18-16

This commentary, though well written, leaves out the most important impact TVA, as a federal government model, has on government in general. The U.S. Constitution must be ignored and replaced with a vague, directionless and opportunistic mix between the very bright line that separates government into three parts.

That has been the problem with TVA from its very start in 1933. FDR called TVA “neither fish nor fowl,” neglecting to identify where TVA fits in.

Your treatise is not much more than a template for a dissolute, dysfunctional government. The actions we take and the programs we cook up all need to go through the filter of our Constitution. All others, like TVA, should be rejected.

Check out how burdensome the federal regulations have become, just concerning TVA, and their effect on the South.