Tucked between northeast Nepal and southern Tibet, the Khumbu Icefall slides down Mount Everest an average of three to four feet each day. The icefall’s crust is a Jenga-pile of house-sized ice blocks that break and collapse without warning. Crossing this part of the glacier is the most dangerous, terrifying section of the trek to the summit. With such incredible natural beauty, it’s hardly a surprise that Everest is a premier tourist destination. All this attention, however, comes with an incredible environmental cost; Everest is a living, breathing mountain, and its pull on climbers may ultimately result in the destruction of its unique natural environment.

The typical Everest ascent lasts about two months, most of which is spent acclimating to the extreme altitude and making test runs along adjacent mountains. By the end of every March, as the Everest climbing season begins, a tent village coagulates at Base Camp, about 40 miles east of Nepal’s capital Kathmandu. As expedition teams gather to rest and refuel in between hikes, more than a thousand people bustle around the glacier, preparing for or supporting the many treks.

Base Camp, which sits at an elevation of about 17,500 feet, is the first of a string of camps dotting Everest’s south shoulder. As climbers acclimate, they incrementally advance through four intermediate camps, each between two and three thousand feet apart. Every step toward the summit draws the climbers deeper into a harsh landscape, requiring oxygen masks to supplement the thin air. Entering the last camp brings them to 26,000 feet, known as the Death Zone, where acclimatization is impossible and the human body starts to deteriorate. Once there, it’s a final 3,000-foot push to the summit and a long way back down.

Despite the harsh Himalayan environment, thousands of foreigners flock to Nepal annually, keen to see and even reach Everest’s iconic 29,029-foot summit. For summit aspirants, it’s a long, arduous journey — New Zealander Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay first managed to successfully reach the summit 32 years after Britain’s first trial expedition in 1921. Since then, over 280 people have died and more than 4,000 have summited. As the Western mountaineering enterprise grew in the late 20th Century, tourism quickly became Nepal’s primary industry, contributing over $1.6 billion to the nation’s economy in 2015. While more mountaineering tourism means more profits, a boon to the world’s 19th poorest country, it also means more physical bodies traversing the precious, delicate alpine landscape, with terrible environmental consequences.

The human footprint has stretched far across the Himalayas, resulting in deforestation across many areas after years of scavenging material for buildings and firewood. Around a third of the way up Everest, the landscape shifts from rugged shrubbery to alpine tundra, marked by the absence of large wildlife and an inhospitable climate. The frigid temperatures in the alpine tundra impede decomposition, leaving organic matter or other items that would normally take mere months to decompose in other climates sealed in permafrost for thousands of years. Changes made to the fragile alpine — whether human-caused erosion, or pollution, the indirect effects of systemic global warming — are just as tragic as they are permanent.

With hundreds of bodies working, living, cooking, eating, and defecating along Everest each year, the environmental toll is extreme. In the 2013 season alone, 658 people reached the summit; in 2012, a record 234 people peaked on the same day, and these numbers don’t account for the many other unsuccessful trips. While the Nepalese government has tried to keep environmental concerns on its radar, the financial incentives have traditionally echoed louder and received more attention during policy-making. It’s simple: The more people visit Everest, the greater profits are, and cleaning up after the tourists requires large expenditures. It wasn’t until the 1980s that climbers themselves took note of the trash devastating the mountain and organized teams to clean the slopes.

Since then, as Everest’s popularity has grown in tandem with environmental demands, the Nepalese government has implemented a minimalist framework for ensuring conservation. The newest regulation is a law mandating climbers return with 18 pounds of trash in addition to their own waste or forfeit a $4,000 “environmental” deposit. According to environmentalist and mountaineer Colin Merrin, there’s little evidence that these rules have had an effect, as significant amounts of trash still litter the slopes, especially lightweight and unwieldy refuse like tent flies and aluminum poles that don’t contribute much to the weight requirement.

On top of these feeble efforts, one other waste material has remained virtually untouched by any conservation effort: human waste. Over the 62 years that humans have been infiltrating Everest’s fragile landscape, climbers above basecamp have “buried their excrement in hole toilets they dug by hand in the snow, chucked it into crevasses, or simply defecated wherever it’s convenient, often within feet of their tents,” according to climber Brent Bishop. Removing human waste, along with any other trash items, is a mountaineering courtesy embedded in the universally accepted “leave no trace” refrain. It’s a useful standard, but it’s unclear how easily it can be applied to the taxing Himalayan climbing conditions.

Climbers may fail at adhering to the “leave no trace” rule of thumb, but the lax environmental standards on Everest are understandable. With harsh, potentially life-threatening conditions, “Your morals start to become pretty gray,” says Merrin. Climbers think, as Merrin notes, “it’d be really nice to bring this turd down, but I won’t…and now there’s a turd that will be up there forever.” This human waste problem is not merely an aesthetic issue. When the ice melts off and on during every season, the water absorbs the fecal matter and then trickles down the mountain, first to basecamp and then further in the runoff streams from which the climbers and Nepalis drink.

To help curb human waste problems in the environment, outdoor companies started producing “personal disposable toilets,” known colloquially among mountaineers as Wag Bags, which are little more than sealable plastic bags with special gelling compounds to help neutralize smells. They’re easy and cheap to produce, at only about one dollar each. Other world-class mountains, like Denali, North America’s highest peak, require climbers use Wag Bags to remove all their feces and have obtained substantial results. According to Denali Ranger Roger Robinson, “the solution had to be simple, convenient, and enforced.” On Aconcagua, South America’s highest summit, rangers guarantee that everyone uses Wag Bag by requiring climbers to check out the bags at their base camp and return them for disposal or risk a fine. Wag Bags could be Everest’s great fecal solution. Introducing disposable toilets on Everest would indeed be simple and convenient, but effective regulations need to be enforced, and Nepal, unlike the United States or Argentina, may not be up to the task.

To help curb human waste problems in the environment, outdoor companies started producing “personal disposable toilets,” known colloquially among mountaineers as Wag Bags, which are little more than sealable plastic bags with special gelling compounds to help neutralize smells. They’re easy and cheap to produce, at only about one dollar each. Other world-class mountains, like Denali, North America’s highest peak, require climbers use Wag Bags to remove all their feces and have obtained substantial results. According to Denali Ranger Roger Robinson, “the solution had to be simple, convenient, and enforced.” On Aconcagua, South America’s highest summit, rangers guarantee that everyone uses Wag Bag by requiring climbers to check out the bags at their base camp and return them for disposal or risk a fine. Wag Bags could be Everest’s great fecal solution. Introducing disposable toilets on Everest would indeed be simple and convenient, but effective regulations need to be enforced, and Nepal, unlike the United States or Argentina, may not be up to the task.

The Nepalese government has been mired in political crisis and uncertainty for years. The earthquake in April 2015 that killed thousands of people and destroyed hundreds of thousands of homes disrupted governance. As the government’s corruption and weak links between the capital Kathmandu and rural areas were exposed to international critics’ eyes, the necessity for real governmental change finally reached a boiling point. In response to foreign pressure, a new constitution took effect in September 2015 and the next months, a new president, the country’s second-ever, was elected. Though the changes have been slow and nebulous, with policies getting lost in the bureaucratic shuffle, Nepal’s use of the cataclysmic event as a pivot to redirect toward a better future is worth applauding. As policies continue to be redesigned, the opportunity to preserve Everest’s integrity remains, even if it is neglected in the service of more pressing concerns.

The lack of consistent and strict oversight on Everest reduces the likelihood that climbers follow through with any environmental measures. While the Nepalese government has its hands gripped on permit control — which requires every climber to pay the Ministry of Tourism $11,000 to set foot on the mountain and maintains their credibility on skimpy environmental policy — there is no formal accountability. No mechanism exists to track how the millions of dollars in free revenue are spent once it enters the Ministry of Tourism’s coffers. On most mountains, permit fees are funneled directly back into mountain maintenance, paying rangers to enforce regulations, take care of waste issues, and provide other safety services. The world’s most prestigious and iconic mountain should be held to the same international standards.

The commercialization of Everest is a necessary and worthy endeavor for Nepal. The tourism revenue, critical in the post-earthquake period, is invaluable even to communities that aren’t directly linked to the Western mountaineering enterprises. As the government openly generates millions of dollars in permit fees, there’s no excuse for its inability to enforce regulations, nor is there a reason to ignore mountaineering precedents established on other mountain peaks around the world.

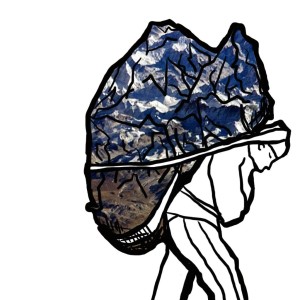

Art by Rebecca Andrews