With $40.9 million in ticket sales on its first day, the Chinese film “The Mermaid” broke global box office records in February of this year. The success of the movie manifests China’s growing presence within the global film industry. Blockbuster successes and an increased partnership between Hollywood and the Chinese film industry have set China on a path to becoming the next leading distributer and producer of films. Yet, despite Hollywood’s interest in expanding the global market for film, China’s production style is intensifying nationalistic sentiments and protection of its domestic film industry. To preserve profits, Western film producers have begun to accede to Chinese media regulatory preferences but at the risk of losing their unique cinematic brand.

Chinese cinema emerged in the 1800s when French shadow plays and American films premiered in Shanghai, the earliest Chinese film capital. As cinematic innovation progressed through the 1920s and onward, the industry yielded a diverse array of films, from family dramas to traditional operatic works to comedies. Simultaneously, Western cinema struggled to attract a strong Asian following due to protests against offensive portrayals of Chinese characters. Following World War II, Chinese film experienced a major transformation as the Communist Party rose to power in 1949. The Party used film, especially newsreels, as a propaganda vehicle to celebrate the revolutionary spirit of Mao’s regime, while censoring other films. Chairman Mao and his allies were greatly involved in the film industry. For instance, the Chairman forced film societies to undergo “rectification” and appointed his fourth wife as Director of Propaganda and as a member of the government’s film advisory committee. Spurred by complaints from artists about creative stagnation, the Communist regime loosened film restrictions slightly in the 1950s, albeit only to quickly fall back into their repressive ways. It was in 1981 that China witnessed the rise of new film institutions, film schools, such as the Beijing Film Academy, and award ceremonies, like the Golden Rooster Awards. Despite these modest advances, government-sponsored propaganda still characterized the bulk of Chinese film.

The turn of the century heralded a dramatic shift in China’s global film presence, particularly since the country’s admittance to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 further opened it to international cooperation. China began to welcome international co-production and build partnerships in Hollywood; the industry’s resurgence was largely buoyed by major blockbusters. But despite the WTO’s opening for transnational film production, China imposed an import quota on foreign films. Criticizing the quota, the US brought a 2007 WTO case against China, who responded by expanding the quota from 20 films a year to the current 34. Chinese implementation of film regulations also may have been a calculated response to the detrimental effects of globalized cinema in nearby markets. By 2000, Hollywood had completely overwhelmed Taiwanese domestic industry by taking 93 percent of film market share.

With new exposure to Chinese works, the international market experienced a change in cultural taste. In particular, the film “Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon” gave rise to a notable turning point that expanded the global audience for Chinese language films. By hiring actors from different Chinese-speaking areas — including mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Malaysia — and by incorporating production techniques from multiple countries, the film epitomized the new, multicultural face of Chinese cinema.

Unsurprisingly, such cultural development has accompanied socioeconomic transitions. China’s phenomenal economic growth has sparked the expansion of the middle class. With a larger consumer class, more disposable income is available to be spent on luxury goods, such as movie tickets. Between 2007 and 2014, domestic spending, a figure that often moves in tandem with total consumption, increased dramatically from $1.4 to $3.5 trillion. Over the same period, domestic box office spending went from less than $1 billion per year to almost $5 billion per year. Consequently, the Chinese film market has responded to consumer needs by building industry infrastructure: Between 2012 and 2015, China’s movie screen count grew from 1,300 screens to a staggering 28,000 screens. Today, the country constructs about 15 new movie screens every day, demonstrating an impressive pace of expansion.

While production has historically been ascribed to smaller private firms, the influence of new media moguls has intensified the scale of production capabilities. The Dalian Wanda Group, a leading real estate corporation led by billionaire Wang Jianlin, has dominated both the domestic production industry and foreign distribution. The firm is currently spearheading the $8.2 billion dollar construction of the nation’s largest movie park in the city of Qingdao. Set for completion by 2017, Qingdao Oriental Movie Metropolis will house Wanda Studios, featuring 30 soundstages, an underwater stage, an outdoor stage, and a New York City street replica. The project will also incorporate a theme park, resort, mall, and yacht club complete with a Hollywood-esque, giant lettering of “Eastern Cinema” overlooking the still-incomplete construction site.

Besides bolstering its domestic industry, groups like Dalian Wanda Group are also buying stakes in the American industry. The Dalian Wanda Group made their first major foray into the American industry by purchasing AMC Theatres, followed by Carmike Cinemas, to form the world’s largest cinema chain. Venturing into foreign production, the Group acquired Legendary Entertainment, the studio that produced “The Hangover” and “Jurassic World.” More discreetly, Wang’s fingerprints are all over Hollywood — for instance, he recently donated $20 million to a film museum in Los Angeles and built a $1.2 million housing development in Beverly Hills.

Transactions like these show that China has more than enough resources to throw into the film industry, but, as of yet, it may lack a deep enough pool of creative talent to back up that burgeoning dominance. On the technological front, China currently lags behind the US but could still challenge Hollywood with innovative industry business models. In particular, crowdfunding through online forums, like China’s WeChat messaging app, has immensely influenced the marketing successes of recent film releases.

To further make up for its deficit of creative talent, China currently engages with foreign producers to advance creative exchange. The Chinese industry is especially eager to use co-production to glean creative insights from experienced Hollywood filmmakers. As David Glasser, former CEO of the Weinstein Company, said during the co-production process of “South Paw,” the Chinese “were on the set and involved in production, postproduction, marketing, everything [because] they wanted to learn how we do what we do.”

As the Chinese film industry looks to the US for creative development, the US is looking to the Chinese consumer base to offset high production costs. In the beginning of 2015, three major box office hits — “Cinderella,” “Jurassic World,” and “Avengers: Age of Ultron” — relied on Chinese box office sales to comprise almost 25 percent of their international gross sales. Because these films involved substantial special effects and costly stunts, huge revenues abroad allowed film producers to recoup the high production costs. More importantly, because co-produced works between Chinese and American filmmakers don’t qualify as foreign films, they avoid China’s import quota. As a result, many more films have recently resulted in partnerships between international firms. For example, the wildly successful “Kung Fu Panda 3” was a joint venture with DreamWorks, China Film Group Corporation and a new firm, Oriental DreamWorks, a spinoff of the original company. Other Western organizations, like the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) and IMAX have expressed interest in collaborating with the Chinese as well.

Despite the mutual interests of the Chinese and Hollywood, the exchange is far from equal. China currently enforces strong regulations that favor Chinese films and values. As a result, Hollywood film revenues are falling annually while domestic films are gaining traction. This trend is largely attributable to China’s rigid film import quota. Besides the quota, China has taken other protectionist measures such as banning foreign films during major cinema-going seasons, like Chinese New Year, and subsidizing domestic films. Those promoting national Chinese values are especially rewarded; for instance, one film was awarded $500,000 for promoting respect of elders. The government has allegedly even intervened directly with ticket buyers: In 2015, audience members who purchased “Terminator” tickets reported that they were given tickets to an entirely different, government-sponsored film instead.

While this kind of favoritism hurts foreign films in China, flat-out censorship remains the biggest barrier to open and equitable global film exchange. The price of ignoring the censorship regulations of this new market is hefty: When Chinese government censors rejected the film “Captain Phillips,” the film’s producers missed out on a predicted $9 million in revenue as a result. In the past, failure to abide by regulations has not only tanked individual films but also threatened entire corporations and filmmakers’ presence in Chinese markets. After the 1997 release of “Kundun,” a film about Tibet, China threatened to ban the Walt Disney Company from engaging in future business in the country. The movie’s director, Martin Scorsese, faced a permanent ban from China after the film’s release. According to these censorship regulations, foreign films can be banned for depiction of anti-Chinese sentiments, socially immoral behaviors, supernaturalism, criminal activity, and sexually explicit or violent material.

As a result of these horror stories from international film companies, many films are now carefully edited to comply with Chinese censorship laws. To sidestep this risk, films have cut out various types of material that could fall under any of these categories. These edits range from the innocuous removal of a shot of clothes on a clothesline in Shanghai in “Mission: Impossible III” to the deletion of a scene depicting the killing of a Chinese security guard in “Skyfall.” Film producer Robert Cain astutely predicts, “You won’t see a Chinese villain probably ever again in a Hollywood movie.” Even positive depictions of other nations’ values or strengths can be interpreted as problematic. “Captain Phillips,” for instance, was rejected by the Chinese government because it praised US military values.

In anticipation of the threat of censorship, Hollywood producers have catered works to Chinese audiences to facilitate easier acceptance in the market. Oftentimes, for successful co-production agreements, works need to incorporate certain elements, including scenes shot in China, Chinese actors, or any details that depict the country positively. Recent examples of successful films that attracted Chinese audiences include “Gravity,” which compliments the Chinese space program by depicting it as the rescuer of the astronaut protagonist. Similarly, “Iron Man 3” added Chinese actors and product placement of a Chinese brand milk and a Chinese bankcard in shots. These seemingly harmless subtleties will certainly be on the rise, and US filmmakers may find themselves in danger of becoming China’s latest mouthpiece.

In the coming years, China’s film industry will grow exponentially by drawing from the creative and technological skills of the West, rapidly expanding the nation’s cultural influence. However, it’s also quite likely that the Chinese state is expected to simultaneously continue to limit American filmmakers’ potential gains by continuing to promote domestic interests and impose strict regulations. Thus, American dependency on economic profits may lead to an asymmetry, as Hollywood is forced to acquiesce to Chinese preferences by portraying the Chinese state in an unchanging, positive light.

For now, both China and the US can hope to benefit from increased global film exchange and new audiences. Perhaps an expanded mandate by the WTO could spur a change to reduce pressures on the US to conform to Chinese standards. But instead of waiting for an international decision that may never come, Hollywood’s best path forward may be to engage more fully in co-production and to tailor material for Chinese audiences. This shift of the cinematic balance of power may expose the West to fresh perspectives and cultural attitudes, but it remains to be seen whether increasingly globalized, co-produced works will be possible or even palatable across international borders. Although we can only theorize what a completely integrated Sino-American film industry might look like, when borders and tastes converge, it’s important to consider the cinematic homogeneity that could arise regarding both thematic content and aesthetic representation. With increased globalization comes increased economic — and in this case, artistic — dependency and vulnerability. Unless Hollywood is fully prepared to significantly alter the flavor of its current and future works, the American industry risks prioritizing global economic interests at the cost of compromising individualistic, creative cinematic expression. China, on the other hand, will reap enormous box office gains while simultaneously profiting from a public diplomacy boost by Western industry — and the latter’s free of charge.

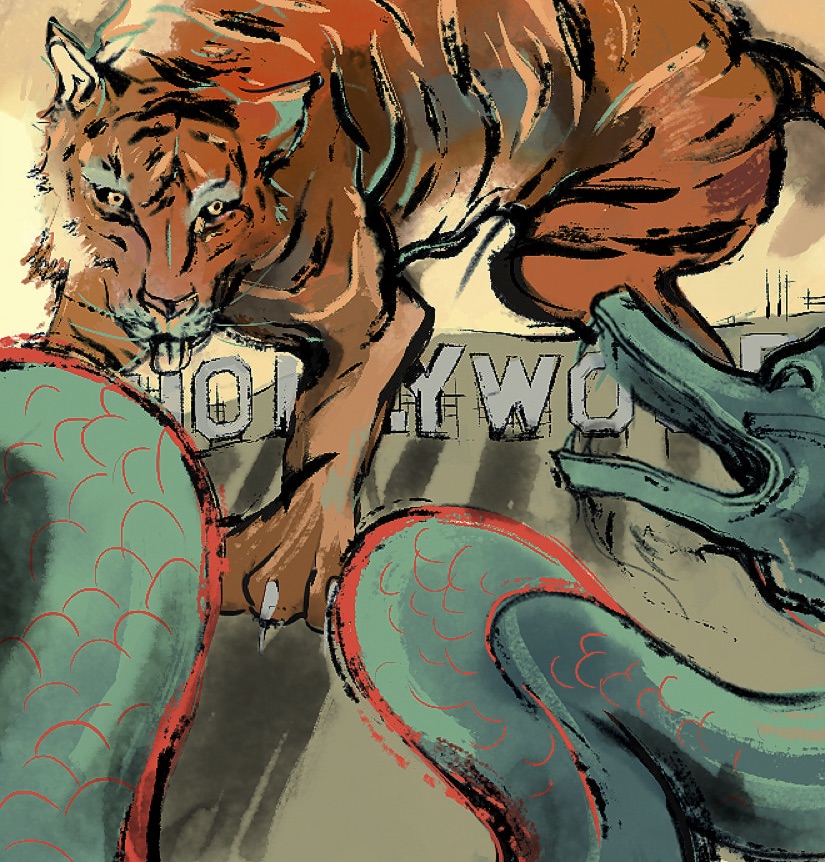

Art by Tiffany Pai