“The only statement I want to make is that I am an innocent man — convicted of a crime I did not commit.” These were some of the last words Cameron Todd Willingham spoke right before he was executed by lethal injection on February 17, 2004. As it turns out, Willingham was right. Six years after his execution, the evidence proving Willingham’s innocence was finally fully compiled. After being presented the evidence, Judge Charlie Baird wrote an order that would have declared Willingham an innocent man if it had been released before his death.

This story, among others, raises an important question: Why are we not talking about the death penalty? In a system where a man like Willingham can be retroactively and incontrovertibly proven innocent, how can a contentious topic like the death penalty stray from the public’s eye? Even the staunchest supporters of the death penalty can see the problem with an innocent man being legally executed. Of course, to think that years later many Americans would still be talking about the Willingham news is naïve, but this example merely highlights one side of the multifaceted problem that is capital punishment. The death penalty — along with its controversial questions of morality, legality, and civility — has fallen into the background of the American political conversation, but its barbaric and often brutal nature should not prevent a meaningful national discussion.

Looking to history, the death penalty was once one of the most hotly debated issues in American politics. During the 1950s, a large-scale movement was started to abolish the death penalty entirely. The nationwide debate was punctuated by television interviews, educational books, and dramatic movies such as I Want to Live!, the story of a death row inmate executed in 1955. Many of these featured actual accounts from death row inmates. This time period came to a head with the 1972 supreme court case of Furman v. Georgia, in which the Supreme Court declared the death penalty unconstitutional due to its arbitrariness. As time passed, however, states set direct and specific circumstances in which the death penalty could be applied, and four years later the Supreme Court reversed its decision in the case of Gregg v. Georgia. In effect, these two decisions closed the nationwide discussion. By basing their decision in Furman v. Georgia primarily on the arbitrary way in which the death penalty was applied in the case at hand, the majority opinion of the court did not give any merit to many of the other arguments against capital punishment. Not only did this allow for the death penalty to be reinstated four years down the road, it also led to the next several decades being dominated by court cases that merely dealt with the logistics of the death penalty, such as banning children from being executed and not whether or not the penalty itself should be allowed. This turned the issue from something that was viewed as potentially changeable into a seemingly set policy, as the issue had gone to the Supreme Court twice and still stood. As a result, the nationwide discussion of capital punishment fell into the background as new issues such as the war on drugs sprung up and took its place.

In modern day America, however, the issue of capital punishment has become much more complicated than the paltry general discourse of the nation would make it appear. Putting aside the moral arguments, which should be powerful enough in and of themselves to fuel a national debate, the fiscal cost of the death penalty is exorbitant. For instance, in Maryland between the years of 1978 to 1999, the costs for capital punishment cases directly attributable to taxpayers ballooned to $186 million, which seems even more outrageous when considering that, out of all of that money spent, only five executions actually occurred. That amounts to over $37 million per execution. Similarly, in the state of Texas, the nation’s leader in executions, the average death penalty case costs the government three times as much as it would to put that same individual in maximum security prison for forty years. If the death penalty were an ordinary policy matter, its levels of cost alone would likely send governmental officials into a tailspin. Thus, whatever makes the death penalty so difficult to talk about certainly remains overpowering enough to stifle a purely economic discussion.

Concerns over the manner of execution add an additional layer of complication. Since the development of modern execution techniques, which ostensibly reduce levels of brutality despite increased cost and difficult procurement, the lethal injection has become the primary method to carry out executions. However, despite its widespread use, the needle has a shockingly high botching rate of 7 percent. The vast majority of botched executions leads to an extremely painful or slow death for the condemned prisoner.

Finally, the issue becomes even more intricate when considering cases like the one of Cameron Todd Willingham. While it cannot be ignored that innocent people have died at the hands of the state, to some, that is acceptable; the Constitution ensures a fair trial, not a perfect one. Others disagree, saying that it is an irrevocable injustice that must be addressed.

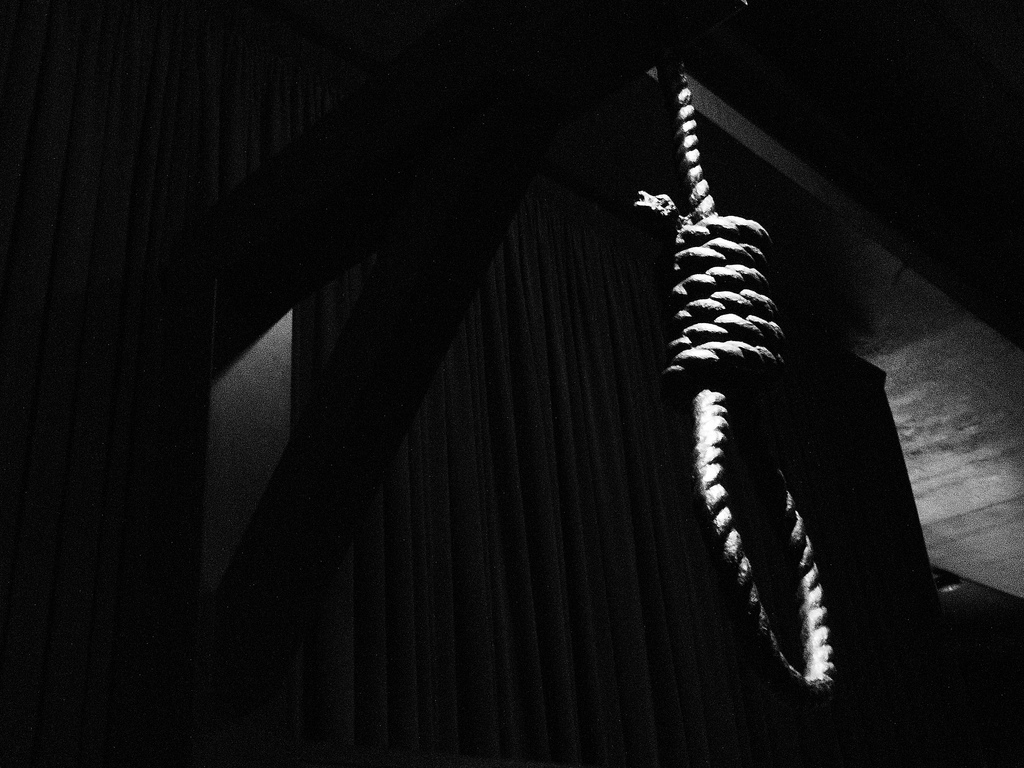

Given that the average American does not have extensive knowledge of many of these issues and conflicts surrounding capital punishment, the national discussion has understandably dwindled to virtual nonexistence. Certainly, a general lack of education about the practical problems surrounding the death penalty contributes to a national lack of urgency, but this is not the whole story. The very nature of the death penalty — a practice that finds its historical origins in decapitations and public hangings, many of which were viewed as entertainment — evokes imagery of blood, brutality, and religious law. It conjures a variety of visceral images, feelings, and reactions in different people. Death is, in and of itself, a characteristically challenging topic to discuss, not to mention the state-sponsored death of a fellow citizen. Therefore, in order to increase awareness about this important policy and its moral consequences, there needs to be improved education on its perilous and often ignored effects — including the economic ones. Only through proper contextualization and framing can the necessary nationwide discussion begin to occur.

Unfortunately, the death penalty is not a highly incentivized issue for politicians to address. Campaigning on a platform against the death penalty only nets you a small portion of people, as it seemingly only affects criminals and not ordinary citizens. Since the vast majority of Americans are not informed on the costs, botching rates or issues on innocence surrounding the death penalty, a great weight falls upon political activist groups to be catalysts of change. Groups such as the Death Penalty Project and Amnesty International push for change by hosting educational events and attempting to spread as much awareness on the issue as possible. By sharing more information on the detriments that the death penalty imposes upon American society at locations such as high schools and college campuses, a new generation may be ushered in that fully understands this issue.

Still, how does the ball get rolling on an issue that will likely not ever effect the vast majority of Americans? Most are law-abiding citizens who will never have their life on the line or even know anyone that will. Even of those who do break the law, only a tiny subsection of them will ever face the possibility of the death penalty. This issue is already scarcely discussed due to its inherent nature, but given that it affects so few people, the media unsurprisingly often covers more universally concerning issues, such as immigration, national security, and taxes, which affect the day-to-day lives of millions of Americans. The media only focuses on the death penalty when the nation gets swept up in some frenzy over one person, where disentangling one man’s trial and guilt from the larger issue of state-sanctioned murder becomes difficult. In that moment of national sensation, no sane politician or public figure would ever risk looking “pro-murderer” by denouncing the usage of the death penalty. This rhetoric places yet another roadblock in the conversation surrounding the death penalty.

Only through information and discussion can the roots of change be planted. It is time to talk about the millions upon millions of dollars that are wasted to maintain the institution of the death penalty. It is time for the United States to decide if it wants to remain as one of the only industrialized countries in the world that still maintains such an antiquated practice. It is time to talk about the poorly carried out methods of execution, nothing short of cruel and usual punishment, resulting in slow painful deaths for some condemned prisoners. It is time to talk about innocent people being torn from their friends and families to die at the hands of the state, all for a crime they did not even commit. It is, at long last, time to talk about the death penalty.