It’s a rare occurrence for a large corporation to lose a lawsuit to the federal government and have it result in a hefty fine. But when it does happen, it’s a NYT-alert worthy moment. Cases like Toyota’s, in which it was charged a $1.2 billion fine after wittingly deceiving its customers about compromised safety measures, make a splash in mainstream news. But even in the presence of high-profile examples like this, it remains the case that, large corporations luxuriate in a bastion of privilege that frequently safeguards them from the auspices of the law — even those laws to which a single individual committing a similar crime would typically fall victim. In the few instances that these companies are held accountable for their misconduct, their reprisal tends to elicit within the public a subliminal sense of joy; however, even if we are happy that justice is served, it’s important to consider where these exorbitant penances go. Does that fee money ever come back to benefit normal people?

The not-so-sexy answer is that it depends. Typically, these federal fines go to the Treasury Department’s general fund due to the general nature of harm inflicted by these kinds of crimes. The Treasury uses this fund to finance the operation of the government. Often some of this sum gets randomly allocated to states and federal agencies—a process that occurs after litigation finishes. And in cases like those of big banks after the financial crisis, some of the fine revenue went to homeowners particularly victimized by the risky mortgage lending of JP Morgan, Citigroup, Wells Fargo, etc. The Treasury Department serves as the government’s bank, so in theory these fines would trickle down to the services all citizens rely on. However, the government isn’t generally celebrated for its efficiency and fiscal prudence. This circuitous, “trickle-down” system presents the question: Is there a way to take better advantage of these opportunities?

A certain subset of companies under the scrutiny of the Justice Department are tech companies, like Google, Yahoo, and Apple. In 2014, for example, the US government fined the search engine giant $500 million for abetting an illegal distribution of pharmaceutical drugs. As usual, these fines followed the path of the many beforehand, but these particular companies pose a unique opportunity for the government.

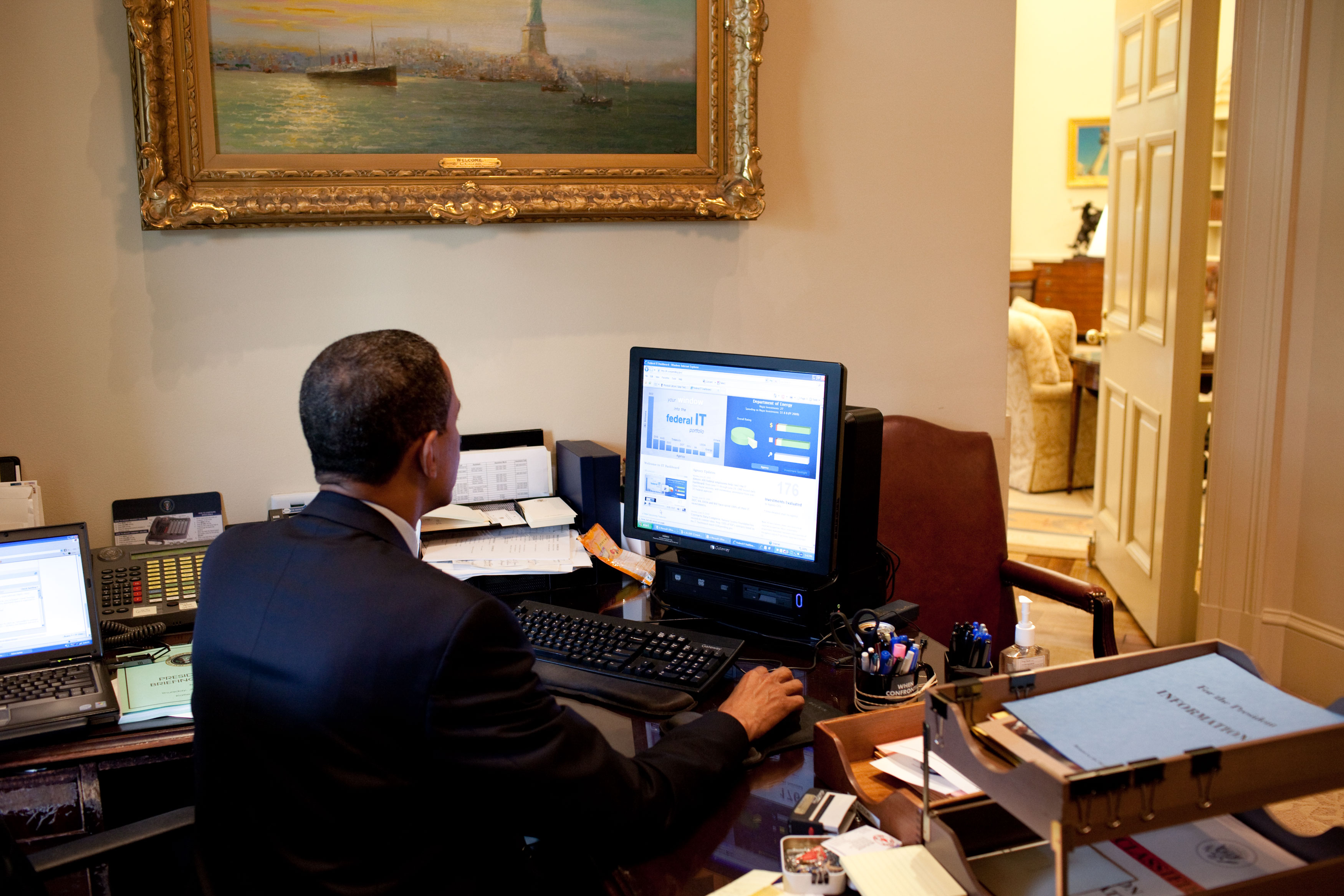

As the Fiscal Times points out, the government spent $75.6 billion dollars on IT projects in 2014. But 70 percent of that cost can be attributed to mere maintenance of their archaic software systems. This ancient infrastructure exposes government to security breaches, as the systems are too old to protect from any decent modern invasion. The Chinese Government’s hack of the Office of Personnel Management isn’t all too surprising considering that the databases, which use technology that predates the Internet by over a decade and contain the Social Security Numbers of federal employees, weren’t encrypted.

The Government Accountability Office released a report in May divulging the shocking and dire situation posed by aging legacy systems. Notable citations include the Department of Defense’s usage of 8-inch floppy disks, which were first used in the early 1970’s, to orchestrate nuclear weapon operations. The Department of Veteran Affairs still relies on a 53-year-old system for their personnel and accounting data. The annual tracking and validation of visa information for over 50,000 foreign nationals runs on 26-year-old infrastructure that not even the vendor continues to support. The US Navy reportedly pays Microsoft $9 billion per year for the 14-year-old Windows XP, software that no longer even gets security updates. The recent controversy surrounding Hillary Clinton’s email has also revealed the outdated systems used at the State Department, which led to several high-level officials resorting to personal emails in order to get anything done.

With an acute need to update its IT infrastructure, perhaps the government should use these legal triumphs over tech companies to negotiate software and hardware contracts. A sum like the $500 million Google was fined would easily cover the cost of overhauling entire federal agencies while eliminating costly maintenance costs. One obvious example would be the transition from decades-old servers to the cloud. While programmers can’t even secure the government’s antiquated systems, cloud storage servers are constantly updated to defend against the newest security vulnerabilities. Further, they add unparalleled efficiency compared to servers. With the cloud model, the government only needs to pay for what it actually uses in storage (as opposed to purchasing entirely new servers after outgrowing current capacity). Technology companies are ready to cater to the highly bureaucratized and regulated requirements of the US government. Amazon already has a specific cloud service to accommodate these mandates, for example.

As it stands, updates to IT infrastructure require Congress to allocate new funds specifically for that purpose; however, budget cuts often slash these resources first. When there’s billions of dollars already going to software maintenance, there’s little incentive to set aside additional funds for new software. As it now stands, the government intends to spend $7 billion less on technology modernization in 2017 than in 2010, while expending ten times that on maintenance.

However, the incentive of gaining new products and services could pose ethical concerns for judicial prosecution; if the government knows it can directly benefit from prosecuting tech companies specifically, they may become unfairly targeted. Even though this might be a legitimate concern, the allocation of these contracts could remain random, where there’s no bidding or pre-determined list of agencies that would benefit from the products. This would ensure that the prosecutors in the Judicial Department are siloed from external pressure from specific agencies. This could also conjure up bad optics: one moment the government is willing to reprimand a corrupt corporation, and the next moment they accept goods and services from them.

However, there doesn’t seem to be that large a gap between products or services, and fines the government uses to pay its bills. Along the same vein, some might wonder why infrastructure is such a valuable investment in the first place. Without upgrades in technology government agencies can’t efficiently conduct business — imagine the frustration you experience with old websites and old buggy Microsoft Suites. Now imagine they’re also running on old computers, with old operating systems, and the vendors that could fix them don’t even maintain these systems because they’re that old. In lieu of spending $75 billion on maintenance, that money can go to operational costs, government programs, and long-term investments.

While the primary purpose of these government fines are to ensure that companies don’t continue bad practices, the government could still accomplish this goal by making the financial burden placed on companies be one that also helps bring the federal government’s technology into the 21st century.