On September 2, 2016, thousands of American pastors and across the country took to their pulpits as part of the annual “Pulpit Freedom Sunday” to discuss the relative merits of the two most unpopular major party candidates for President on record. Their coordinated – and surprisingly bipartisan – effort to make their voices heard was part of a broader nation-wide struggle to come to terms with polarization and civic duty in a nation on the verge of a breakdown. It was also, according to a few short lines in US Internal Revenue Code, illegal.

Illegal is perhaps too strong a word. The penalties for violation, after all, are not criminal. But the reality of the so-called “Johnson Amendment” is just as pernicious. Enacted without fanfare in 1954 at the behest of then-Senator Lyndon Johnson, it empowers the IRS to strip 501(c)(3) organizations (a category including most religious groups and many secular charities) of their tax-exempt status if they contribute to specific political campaigns or initiatives. That ban covers everything from fundraising for political action committees to endorsing candidates for office, preventing nonprofits from engaging in direct political intervention except to assist movements totally unconnected to candidates. An accident of history, the Johnson Amendment is blunt and ineffective as a weapon against money in politics, and downright un-American as a weapon against religion in politics that limits constituents’ ability to give voice to their conscience. Congressional leaders on both sides of the partisan aisle should commit to ensuring that 2017 is the year it dies.

The ultimate irony of the Johnson Amendment is that the largest political fault line associated with it – political activities by religious non-profits – was hardly addressed by the amendment’s authors. George Reedy, Johnson’s chief aide in 1954, later wrote that “Johnson would never have sought restrictions on religious organizations.” Nor, evidently, did any sitting Senators object on these grounds: the Amendment, inserted quietly into an omnibus bill, passed by voice vote within minutes of its introduction. There was, quite literally, no debate.

That the Johnson Amendment was anything but controversial when first passed touches on the fundamental reason it so threatens to distort our politics. The Johnson Amendment was only politically possible because its religious dimensions were not clear when it was passed. Those dimensions were not apparent because American religion was, by historical standards, remarkably homogeneous and consciously apolitical. The 1950s, after all, were the high-water mark for church attendance and religious consolidation. In 1950 some 69 percent of Americans identified as traditional Protestants, with the majority of them belonging to the moderate, old-school, “mainline” denominations, such as Episcopalians and Methodists. Catholic-style hardline views on abortion had yet to move into the mainstream, large-scale mobilization by black churches against segregation was still several years out, and the sexual revolution of the 1960s was nowhere in sight. It stands to reason, then, that the ideal of apolitical religion had far more cachet in 1954 than it does today.

But the American religious landscape is changing rapidly – and has been for decades. Fewer Americans identify as members of any organized religious group. This decline, however, has not occurred within the most devout sector of the population, but rather within the share of the population identifying as only somewhat faithful. The numbers of the devout, meanwhile, have more or less held steady, but they have splintered. The old-school mainline Protestant churches and the Catholic church have seen attendance slide the most. The beneficiaries of this shift have largely been smaller, non-traditional alternatives to the old mainstays: Pentecostalists, Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Orthodox as opposed to Conservative Jews, and so on. By 2014 the percentage of evangelical Christians who identified as non-denominational had reached 30 percent, up fivefold since 1972. The trend underway is a relaxation of the iron grip a few colluding power-players and the development of a more competitive system. And one of the obstacles to that shift is the Johnson Amendment. For groups with large numbers of adherents like Catholics or with an exceptionally well-organized church bureaucracy like Mormons, or followers of the late Jerry Falwell, this barrier is easy enough to hop over. But sermons and direct action are in some cases the only tools available to affiliates of smaller organizations and those with poorer or less-educated congregants. The chief effect of the Johnson Amendment, then, may well be its limiting effect on political expression by minor religious groups.

This should alarm us, and not merely those of us who belong to the religious groups disadvantaged by it. Our constitutional system requires not only that the formal powers of the state are dispersed and jealously guarded by their respective caretakers, but also that the interest groups seeking the sanction of those powers should be numerous enough to prevent others from dominating the political life of the country. Historically, American religious diversity has been central to that multitude of opinions. It was the organizing capacity of black churches that ensured the whole world was watching a bridge in the small-town of Selma, Alabama on one bloody March day in 1965; it was religious agitators like Henry Lloyd Garrison who played a pivotal role in putting sufficient pressure on Northern Congressmen to break the spine of the congressional gag rule on the discussion of anti-slavery petitions in the 1850s. No legal barrier will ever end religious involvement in politics altogether. However, repealing the Johnson Amendment would actually strengthen that involvement and thus the institutions they uphold. It may, consequently, have the positive corollary effect of mitigating some of the well-known negative social effects of the decline of traditional religion, such as increased support for political extremism and a higher rate of substance abuse, especially in rural areas. And we should remember that the Johnson Amendment doesn’t merely restrict religious groups. All Federally-recognized nonprofits face the same restrictions, and they play the same vital role in our political system: as dissenting voices in the collective conscience.

But by letting the Johnson Amendment survive we risk lapsing as a nation into the kind of European anticlericalism – most obvious in France since the Revolution – which treats any form of religious expression with suspicion. For some of the Johnson Amendment’s most ardent supporters, of course, this may be the goal. The Wisconsin-based Freedom From Religion Foundation (FFRF), for example, has challenged the constitutionality of White House faith-based outreach initiatives. In 2011, FFRF co-founded an initiative to help ex-clergy “connect with other religious professionals… who no longer hold to supernatural beliefs.” Still others, like Mark Oppenheimer at Time, believe that the Johnson Amendment does not go far enough, and advocate instead for the taxation of church property.

But out-and-out anticlericalists are few and far between; proponents of the Johnson Amendment usually couch their views in more outwardly sympathetic terms. Repealing or relaxing existing restrictions, they argue, would damage American politics, and would weaken the foundations of American religion by mixing the spiritual and the political. The paternalistic implication of the latter notion is that religious organizations must be muzzled for their own protection because they simply do not know any better. As Baptist Pastor J. Andrew Daugherty put it in a Huffington Post editorial in February, “religious allegiances should always transcend… political alliances.”

What if Americans did away with the strange fiction that non-profits ought be apolitical and immune to controversy? Would American religion then be forever tainted by earthly prejudices and easy money? Consider the case of the All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena, which was presented in 2005 with a letter announcing an IRS investigation threatening to strip the church of its tax exempt status for a 2004 anti-war sermon delivered by its former rector. It is difficult to imagine that even the most ardent supporters of the Johnson Amendment would genuinely believe that the IRS was actually protecting All Saints Episcopal by hanging a Sword of Damocles over the church’s head. The sermon in question was of exactly the tenor that Daugherty condemned earlier this year; should All Saints Episcopal have set aside the convictions of its rectors for the sake of secular comity? The only thing threatening to “pervert” American religious practice is the government dictate that bans religious groups from speaking out against what they perceive as injustice. An apolitical religion that fails to grapple with metaphysical truth because it is afraid of the taxman is a dead religion.

Repealing the Johnson Amendment, furthermore, need not open our politics to a flood of dark money. For example, the “Free Speech Fairness Act” (H.R. 781), introduced in the US House of Representatives in February by Representatives Steve Scalise (R-LA) and Jody Hice (R-GA), would allow 501(c)(3) organizations to support or oppose candidates for office provided they keep related expenditures to a minimum. The bill is narrow in scope and strikes a good balance between relaxing barriers to entry for non-profits and preventing an influx of political cash. Passing it would be a good starting point. More expansive reforms, such as an end to the prohibition on monetary contributions by non-profits, could come later. If, as some have argued, tax-exemptions for political organizations would effectively constitute subsidies for political speech, Americans should carefully consider whether this is really as dangerous as it seems at first glance. Voluntary associations are a uniquely powerful social lubricant and key to the health of any republic, and there are far more effective methods of preventing our politics from drowning in big money. For example, establishing a more robust public campaign finance system or genuinely enforcing the laws that ban coordination between campaigns and SuperPACs. It is difficult to imagine that a nation as populous and creative as ours cannot imagine any check on money in politics more effective than the Johnson Amendment. Nor is it likely that Americans will stop giving to the most uncontroversial, clearly apolitical nonprofits if the Johnson Amendment is repealed.

It just so happens that the most prominent public advocate for reforms of this nature is also the most likely to taint it by association. The Johnson Amendment was one of several targets of a rambling, self-congratulatory commencement address delivered by president Trump in May at Liberty University, a conservative Christian college in Lynchburg, Virginia. The president, who had recently issued an executive order directing the IRS to de-prioritize Johnson Amendment enforcement, promised that “[a]s long as I am President, no one is ever going to stop you from practicing your faith”.

As well he might. Our president makes a lot of noise, but we should not be afraid to agree with him when he is right. And while a man whose best attempt at demonstrating piety was a half-baked reference to “Two Corinthians” is hardly the best spokesman, the mere fact that Mr. Trump opposes the Johnson Amendment does not a counter-argument make, any more than the fact that the Nazis campaigned against smoking can be an argument for ignoring lung cancer.

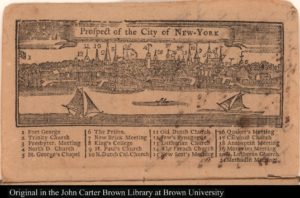

The gothic spire of New York City’s Trinity Church would not look out of place towering over the centuries-old buildings of any Western European city center. But it is hard to imagine another place on earth where it would appear any more stately than it does at the bottom of one of Lower Manhattan’s urban canyons, surrounded by the commanding heights of industry. But long before New York’s titans of industry left their mark on the city’s rising skyline, spires like Trinity’s offered no less spectacular a vista to the visitors thronging the busy harbor below. A 1771 woodcut of New York harbor by Hugh Gaines numbered them like wares in a catalog, 18 in number and each apparently determined to outreach its competitors.

Gaines’s woodcut bears testimony to a legacy of religious diversity and competition that Americans, to our discredit, seem in danger of forgetting. Forget what Thomas Jefferson wrote about a “wall of separation” between church and state; the reality of the American experience has been exactly the opposite. The hallmarks of American religious history have been acrimony, fragmentation, and a relentless intrusion of religious leaders of every possible orientation into mainstream politics – and we have been all the better for it. No republic can survive without introspection, and for much of our history it has been religious organizations that provided that introspection. This country does need to keep religion out of politics – if anything, America needs more religion in politics. And though it is hardly the be-all end-all, killing the Johnson Amendment is a good place to start.

"

"