Although the redistricting process differs across states, the power to draw districts is typically given to state legislatures. Either legislators themselves or a committee appointed by the legislature will do the work of drawing new district lines. There is very little federal legislation to regulate redistricting; just vague laws, such as the Voting Rights Act’s rule against “diluting the votes of racial groups.” Partisan gerrymandering tends to favor the party in control of the state legislature, and party members have no reservations in drawing lines that favor their side. Although most redistricting professionals utilize various types of software technology, these districts can still be easily manipulated to favor particular parties. The process is inherently political, and constitutionally speaking, it’s nearly impossible to regulate on a federal level.

However, one state has utilized a unique system that has kept politics out of redistricting. The small state of Iowa uses a redistricting method that is purposefully nonpartisan and purely based on neutral district-drawing. But Iowa didn’t just decide to simply stop partisan gerrymandering, on both sides of the aisle. There is still political polarization and vitriol across the state, just not in the realm of redistricting. So how did they do it?

The answer lies in a piece of legislation from 1980 that established the vaguely-named “Legislative Services Agency” (LSA) in Iowa. The legislation passed under very specific circumstances: Republicans had majorities in both houses of the state legislature, but feared that they would lose these majorities in the 1980 elections. Democrats, however, had very little confidence that they would take the state legislature themselves, and expected the Republicans to maintain control.

Both parties feared that the other would take the state legislature and heavily gerrymander districts going forward, preventing the minority power from gaining any power in the foreseeable future. Thus, each side had an incentive to pass laws that would protect themselves if they didn’t gain the legislature; both sides wanted to lessen the powers given to the majority party in the form of redistricting reform.

There was no grand agreement, no shaking of hands and decision that gerrymandering was to die in Iowa. Each side was simply afraid of what would happen if they lost. This legislation wasn’t passed under the auspices of ethical superiority or good government; it was passed for specifically political, partisan reasons. Both sides wanted to maintain their own power.

The results of this agreement, born out of political happenstance, have lasted to this day. The effects of this protective measure are still active in Iowa’s redistricting process, and have made a permanent mark on the politics of the state. Although Iowa is the only state to employ its unique independent commission system, the elements of the legislation itself are surprisingly minimal, and seem like relatively obvious steps towards redistricting reform.

Mapmakers are not chosen by the party in control of the Iowa State House, but rather by a neutral group. This group has a very specific makeup, consisting of only five people: one appointed by the majority leader of the State Senate, one by the minority leader, one by the majority leader of the State House, one by the minority leader, and one by the other four. This bipartisan makeup attempts to ensure equal representation in the actual drawing of these maps.

Once the process begins, these representatives are not allowed to consider past election results, partisan voter registration, race, or the addresses of incumbent politicians. They’re not allowed to speak or interact with current legislators, or those running for a seat in the legislature; this ‘political prohibition’ is unique to Iowa. Their goals are clear and simple: compact, contiguous districts that “preserve the integrity of political subdivisions.” The strategies that they use are mathematical and scientific, while also taking into account these specific goals; objective technology must be approved by both parties before it can be used.

Once maps are actually created, they must undergo at least three public hearings. Constituents are encouraged to come out and make sure that they’re being properly represented and apportioned, on the local, state, and federal levels. These maps must then pass both the General Assembly and the State Senate in order to actually be implemented. The process is simple and direct, yet checked at multiple levels by members of both parties.

And it’s worked.

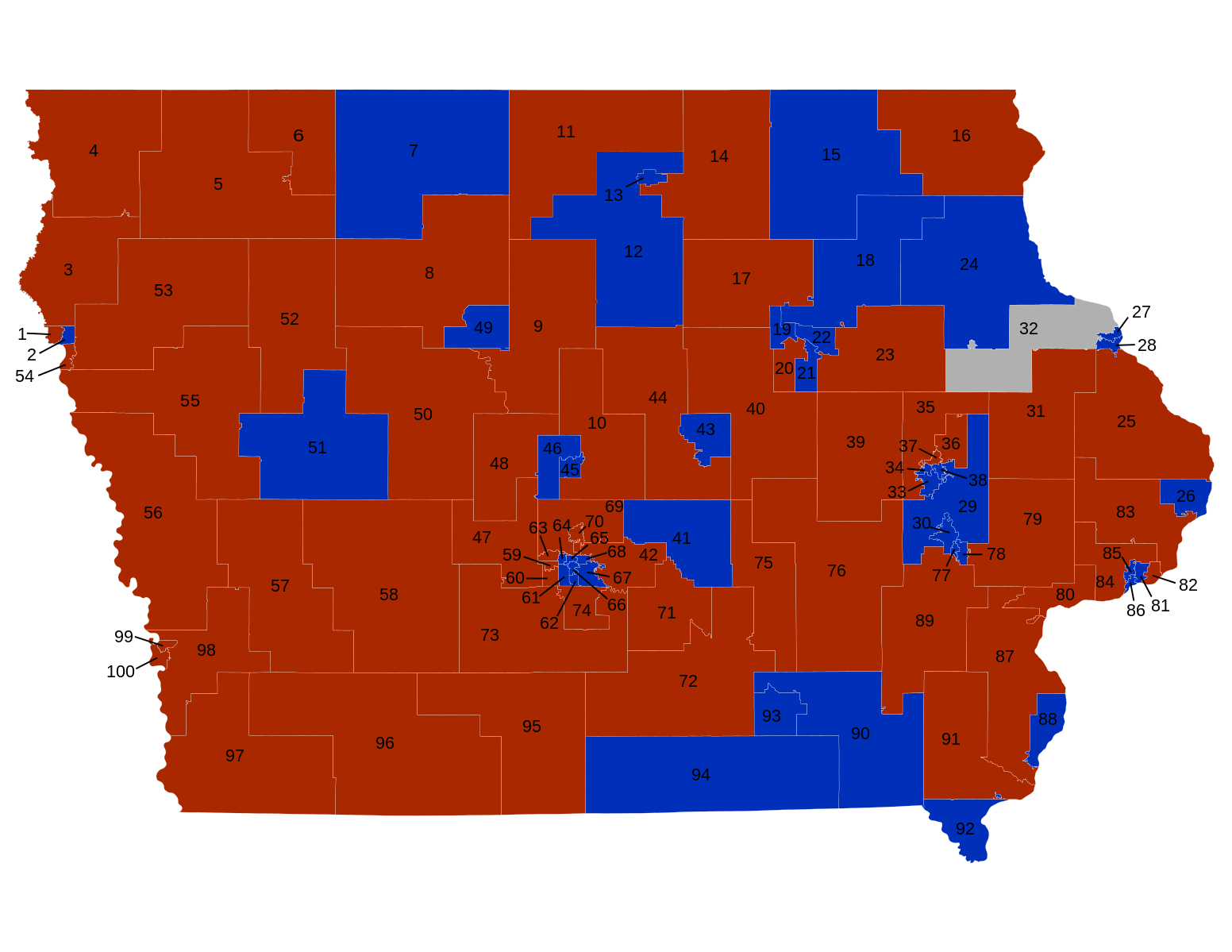

The delegation’s redistricting has resulted in extremely close races in Iowa over the past few decades. Republicans and Democrats have traded control of the state legislature and Congressional seats multiple times in recent years (the General Assembly is currently evenly split between parties), and Iowans on both sides of the aisle have been able to agree on the fairness of the districts.

So why aren’t other states taking up the methods that Iowa has used?

The push for reform by legislators is extremely limited. It makes sense; no legislator wants to pass legislation that is going to make his or her future race more competitive. They want to keep the districts that elected them, keeping the lines in the same places, even if they are discriminatory or unrepresentative. Since legislators themselves have so much control over redistricting processes in most states, the issue is not very transparent to constituents. Even if constituents do want to vote for reform, their votes have already been gerrymandered, and thus are often inconsequential, even if they’re part of the majority.

But the future is not without hope. As technology advances, researchers are more easily able to detect gerrymandered districts and bring them to the attention of legislators. Additionally, more and more cases are being brought to the Supreme Court on the issue, and some states had ballot initiatives regarding gerrymandering reform in the 2018 midterms. In fact, most of these initiatives actually passed, demonstrating the popular demand for reform in this area. Legislators in some states, on both sides of the aisle, are even running on platforms of redistricting reform, and other states such as California and Arizona are slowly implementing reforms of their own.

The issue, however, isn’t that gerrymandering is particularly difficult to detect: We know it’s going on in almost every state, and we’ve known for a long time. The issue is the glaring lack of incentive to reform such polarized, partisan processes in most states, and the subsequent lack of action on behalf of most legislators.

While Iowa might have done the best job of taking politics out of the redistricting process, it’s important to remember the context in which Iowa’s reform actually came about. The motivation wasn’t some high-minded desire to come together and pass bipartisan reform. Iowa’s reform only came about due to a specifically partisan, political situation; the competitiveness in the state is the only reason the legislation even passed in the first place.

There isn’t an obvious answer to solving this blatant lack of motivation to pass gerrymandering reform. While Iowa is a great example of what can happen if this reform does indeed pass, the motivation to pass such reform can’t just be political happenstance if we want it to actually occur. The answer must lie in some bipartisan agreement that crosses party lines, some innate desire to provide accurate and fair representation regardless of prospects of re-election.

This lack of motivation for reform is belied by greater issues of political polarization in our current system, and there is no answer to simply solving this polarization and making it disappear. However, if we want to see what the results are – even if they are a product of mere political coincidence – Iowa provides an illuminating, maybe even hopeful, example.