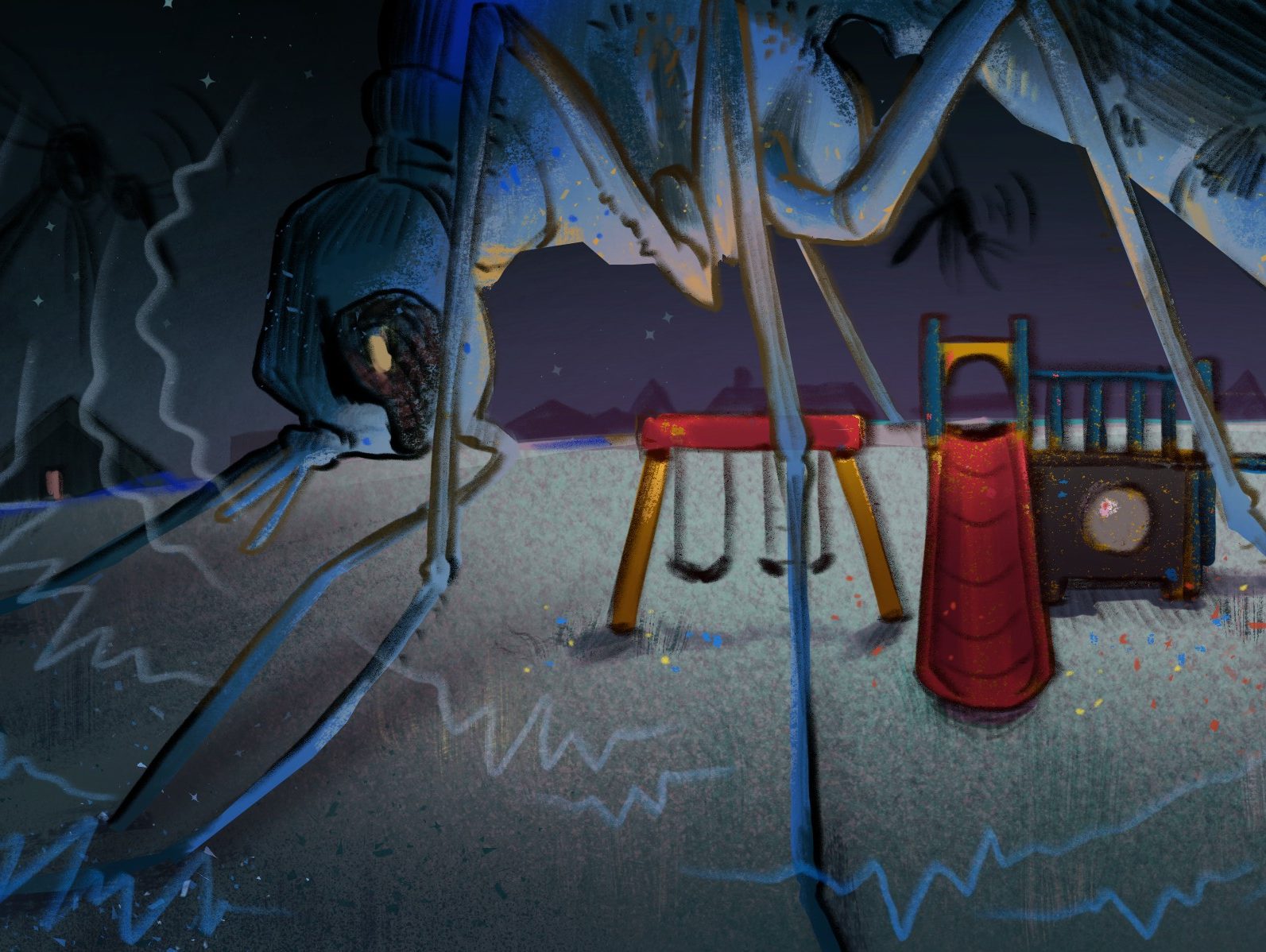

In 2014, Mosquitos began to take over Philadelphia parks, forcing teenagers and young adults out of public spaces at night. Contrary to the images of pesky bugs which may come to mind, the true source of the infestation was a city-wide installation of seemingly inconspicuous sonic devices. However, the employment of such devices could not go unnoticed.

Philadelphia is but one of dozens of cities around the world that have installed noise-making gadgets—aptly named “Mosquitos”—to discourage loitering, vandalism, and other “antisocial” activities. Their target? The city’s young people. Due to the high frequency of its buzzing, the Mosquito is inaudible to individuals over 25 years old but is incredibly unpleasant for people between the ages of 13 and to 25.

Recent backlash against these systems compelled Philadelphia to pause their installations. As the city deliberates the merits of the Mosquito, and as other cities continue to expand its usage, it is critical to examine the ethics of such a device. Ultimately, though many public spaces are restricted at night, the use of these sonic devices poses a unique problem which distinguishes the Mosquito from more traditional security methods: By targeting certain age groups, the device enforces privacy in a discriminatory way. Moreover, its placement in public spaces contradicts the primary purpose of these very areas. Consequently, Mosquitos must be eliminated.

Michael Gibson, the president of Moving Sound Technologies—the device’s manufacturer—denies discrimination charges. He explains that while Mosquitos exist in public spaces, “they’re not actually activated until the park or recreation center becomes private property [at night].” And, he adds, “people have the right to protect their property.” Privacy is indeed a right, but this method of maintaining security is inherently biased. The very nature of the Mosquito means that parks might in theory be private to all at night, but in practice, privacy is enforced only against a subset of the population—those young enough to hear the device.

By installing devices with such blatant age-based discrimination, governments send harmful signals to teenagers. The Mosquito draws upon the stereotype that a disproportionate number of teenagers are rule-breakers. Instead of encouraging youths to pursue healthy, productive activities at night, these sonic devices assume that young individuals will not do so. These assumptions have harmful psychological effects, seventeen-year-old Reed from Philadelphia explains: “It makes us feel like animals. Not all teens are bad just because we want to go outside for a breath of fresh air at night.” More concerningly, many studies have emphasized just how susceptible teens are to outside pressures and expectations. A study conducted at Wake Forest University titled “Stereotypes Can Fuel Teen Misbehavior” even noted that for teenagers, “higher expectations for risk-taking and rebelliousness predict higher levels of problem behavior, even controlling for many other predictors of such behavior.” In other words, the signals sent by the Mosquito may become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The use of Mosquitos is particularly hypocritical when one considers the historical intent of publicly-owned spaces. Public areas can foster a sense of belonging and provide individuals with the opportunity to engage and form bonds with other members of their community. They need not be areas of unrestricted freedom. For example a library limits the sorts of activities deemed acceptable within its confines, even though it is a public space. Although certain activities might be prohibited, public facilities should promote inclusivity and accessibility to all community members. And in many cities, inclusion is more than just the ideal—it is the law. In New York, for instance, “it is against the City Human Rights Law for a public accommodation to withhold or refuse to provide full and equal enjoyment of those goods or services based on… protected classes under the Law.” As one of these classes is age, the Mosquito violates these principles. While gates, security guards, and cameras are all used to secure public property after hours, they do so in a way that targets all individuals regardless of distinguishing characteristics. Sonic devices, on the other hand, specifically exclude young people from public spaces, which should be welcome to all.

Moreover, the funding for these installations presents a rather ironic situation. In general, recreational spaces are created with public money for young people. Now, cities funnel taxpayer dollars into devices designed to keep teens out. Rather than encouraging the use of these facilities for a multitude of productive activities, the city has decided to use public money to criminalize the act of simply existing in these spaces as a teenager.

The harmful effects of these devices are not purely psychological—a number of potential public health issues have also arisen from their installation. A study conducted by the German Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health concluded that the device may disproportionately harm infants and young children, noting they may experience “nausea, dizziness and pain.” Concerningly, their caretakers are often too old to hear the noise and do not know to move the children. Other reports have noted such devices’ disproportionate effects on those whose sensitive hearing cause them to become especially alarmed by the high-pitched buzz. This strengthens the case against the Mosquito.

Unsurprisingly, the Mosquito has already faced several legal challenges. Many organizations assert that Mosquitos infringe upon human rights when installed in public spaces. In 2008, the United Nations Committee on the Right of the Child urged the U.K. to reconsider the use of such devices “as they may violate the rights of children to freedom of movement and peaceful assembly, the enjoyment of which is essential for children’s development.” Just two years later, the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly agreed, calling on its 47 member states to ban the marketing, sale, and use of Mosquito devices, and instead promote “the development of indoor and outdoor facilities to increase opportunities for physical, intellectual and leisure recreation.” Washington, D.C. has also taken decisive action, removing Mosquitos from its parks following the filing of a complaint with the D.C. Office of Human Rights. Thus, there is a legal precedent for the Mosquito’s termination.

Many cities, however, continue to rely on these devices. Despite the backlash, Philadelphia has yet to commit to end its Mosquito usage, even as their very use conveys harmful assumptions about youth and singles out community members based on age. Ultimately, Mosquitos undermine the intent of public spaces. It’s time for Philadelphia and others to follow the examples of D.C. and Europe and eliminate these sonic weapons.