There’s no question about it: prescription drug costs in the United States are unaffordable for many Americans. So whose fault is it? Consumers and politicians generally place most of the blame on ‘Big Pharma,’ alleging that, as the entity responsible for setting drug prices, they must be responsible for the out-of-control costs. Pharmaceutical companies, on the other hand, single out pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) as the root of all evil, alleging that they, the middlemen between manufacturers, pharmacies, and the employers who hire them, withhold rebates and discounts from consumers. PBMs claim that pharmaceutical companies are responsible for setting drug prices to begin with. Meanwhile, Donald Trump thinks that the rest of the world is “freeloading” off of American innovation in the prescription drug sector. With fingers being pointed in every conceivable direction, it’s difficult to really say who is truly at fault. But, like most things in life, the truth lies somewhere in the middle. To boil the issue of high prescription drug costs down to a single perpetrator is to overlook the complexity and nuance of the entire pharmaceutical industry, an industry obscured under layers of intentional obfuscation and special interest.

For starters, President Trump is correct to be outraged about the “unfair…global freeloading” of other nations on the backs of Americans, who are finding themselves responsible for footing the bill of the pharmaceutical industry’s innovation. The United States subsidizes the majority of the world’s artificially low drug prices by the sheer fact that drug prices in the US are up to six times more expensive than the world average. Without America there to foot much of the cost, the rest of the world would be paying substantially more for their prescription drugs. Many politicians fail to acknowledge the keystone financial role that America plays in the global drug market and, instead, cavalierly propose radical solutions to the drug cost issue that are financially unsound. For example, during a campaign speech given in January, Bernie Sanders correctly asserted that Americans pay more for prescription drugs than other industrialized nations. He continued that, under his plan, no American would pay over $200 for prescription drugs. However, such a claim is nothing more than an unrealistic campaign promise that he probably won’t be able to deliver on.

It takes on average 10 years and $2.7 billion to develop a new drug. The majority of this cost arises during clinical testing, the phase of development during which a drug’s safety and efficacy are examined. Before drugs can be sold to consumers, they must undergo rigorous clinical testing to ensure that they both do what they are supposed to and aren’t going to be dangerous for the individual taking it. There are three initial phases of clinical testing, each with different specifications and parameters that must be met in order to pass on to the next phase. If these specifications are not met, then the drug fails clinical testing and cannot be brought to market. 63 percent of drugs typically make it through from Phase I to Phase II. However, that number shrinks to as little as 33 percent from Phase II to Phase III. So every time a pharmaceutical company attempts to bring a novel drug to market, they do so with little confidence of making a return on their investment. Although it remains easy to attribute that lofty $2.7 billion price tag to mere corporate greed, doing so is reductive and fails to factor in the great opportunity cost incurred on pharmaceutical companies.

Clearly, deciding whether or not to invest in a new drug is risky business. In order for pharmaceutical companies to continue innovating, there must exist the appropriate financial incentives. In 1983, Congress passed the Orphan Drug Act, which granted market exclusivity to companies who were able to develop a successful therapeutic that treated rare diseases. This particular line of development is a less lucrative sector of the drug industry, given the lack of volume of customers and substantial up-front investment. The seven-year exclusivity period that pharmaceutical companies were able to secure (along with a few additional tax incentives) increased the number of clinical trials for orphan drugs by 69 percent. Investing in rare diseases is both costly and risky, so why would pharmaceutical companies do so unless there was a chance that they would turn a profit? The Orphan Drug Act demonstrates that, given enough financial incentive to mitigate potential risk, innovation will follow suit. If America decided to regulate its drug prices to match those set overseas, it is estimated that global pharmaceutical profits would drop $134 billion. The University of Southern California’s Future Elderly Model predicts that this change would have a profoundly negative impact on research and development. Simply lowering America’s drug prices, as Bernie Sanders would suggest, is an unsustainable solution that hurts future generations as well as the rest of the world. Advanced nations such as Norway–who can afford to spend more on prescription drugs–set artificially low drug prices by taking the average of the three lowest nation’s drug prices. Other advanced nations in turn match their drug pricing to Norway’s, which leaves the United States as the sole nation responsible for carrying the brunt of the drug’s cost. This responsibility is evident in the fact that the US accounts for between 64 and 78 percent of global pharmaceutical profits annually, making low prescription drug costs abroad a main driver for high prescription drug costs here at home.

Although other countries are responsible for raising American drug prices when they shirk the cost of drug development, other nations are not the only guilty party. A lot of attention is paid to pharmacy-benefit managers (PBMs) for their role in the rising cost of prescription drugs due, in part, to the lack of transparency surrounding their dealings. PBMs act as middlemen between drug manufacturers and insurance companies, pharmacies, and employers. Their job is to leverage their large purchasing power to negotiate rebates from manufacturers so as to pass lower prices to consumers. PBMs claim to pass along 91 percent of rebates to insurers and employers and pocket the other nine percent. However, it is impossible for consumers to actually verify this claim, as PBMs do not release specific prices that are negotiated between manufacturers and pharmacies. Furthermore, given that three PBMs now control over 75 percent of the market, the balance of power in negotiations is greatly biased towards PBMs. Because they face so few alternatives, manufacturers today are forced to acquiesce to the price demands of PBMs and to provide increasingly large rebates so as to not be excluded from a PBMs formulary. As a result, manufacturers continue to increase their list price while PBMs continue to demand larger rebates. This creates a vicious cycle similar to that of EpiPen in 2016, where the price of a two-pack continued to increase each year for no apparent reason until it eventually surpassed $600. In 2007, this same 2-pack only cost $93.88. According to Mylan CEO Heather Bresch, PBMs were the primary party to blame for EpiPen’s high cost because of the substantial rebates they kept negotiating. Whether or not this was actually the case, the math certainly adds up.

However, this is not to say that Big Pharma is completely blameless in the issue of high prescription drug costs. The patent system, which awards market exclusivity to novel drugs so that pharmaceutical companies can recuperate research and development costs, is constantly abused by drug companies. Once patents expire, drug companies are authorized to manufacture generic versions of a drug, which can cost as little as 5 percent of the patent-protected brand-name version. To circumvent the negative financial fallout of an expiring patent, drug companies employ evergreening strategies, such as reformulation, to justify maintaining their high price and market exclusivity. Through making slight changes to the brand-name version of a drug when its patent expires, pharmaceutical companies claim that they’ve created an entirely new drug and are granted a patent extension from the FDA. These modifications could be as minimal as changing the delivery method from a solid to a liquid capsule or changing the dosage in a single pill. Yet, if the manufacturer can prove that there is a difference in efficacy, with “difference” left intentionally vague, then their patent is extended and consumers continue to pay brand-name prices. In this regard, physicians also continue to perpetuate the costly cycle of evergreening by prescribing brand-name versions of drugs that have generic equivalents which cost a fraction of the price. In a recent study, 4 out of 10 doctors prescribed brand-name drugs over generics because their patient asked for it, and many doctors are themselves hesitant to prescribe generics when a “better” version exists for their patients.

No one party is to blame for the high cost of prescription drugs in the United States. Rather, low drug prices internationally, the growing influence of PBMs, and the greed of Big Pharma have all contributed to the skyrocketing cost of prescription drugs. The issue of drug pricing is immensely complicated, with special interest groups looking to make a profit at every turn. Unfortunately, these competing interests have shifted much of the financial burden onto the consumer’s lap. There’s no easy fix. But legislation such as the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015, combined with an assessment of the monopolistic practices of PBMs and a more rigorous patent procurement process for reformulated drugs, is a good place to start.

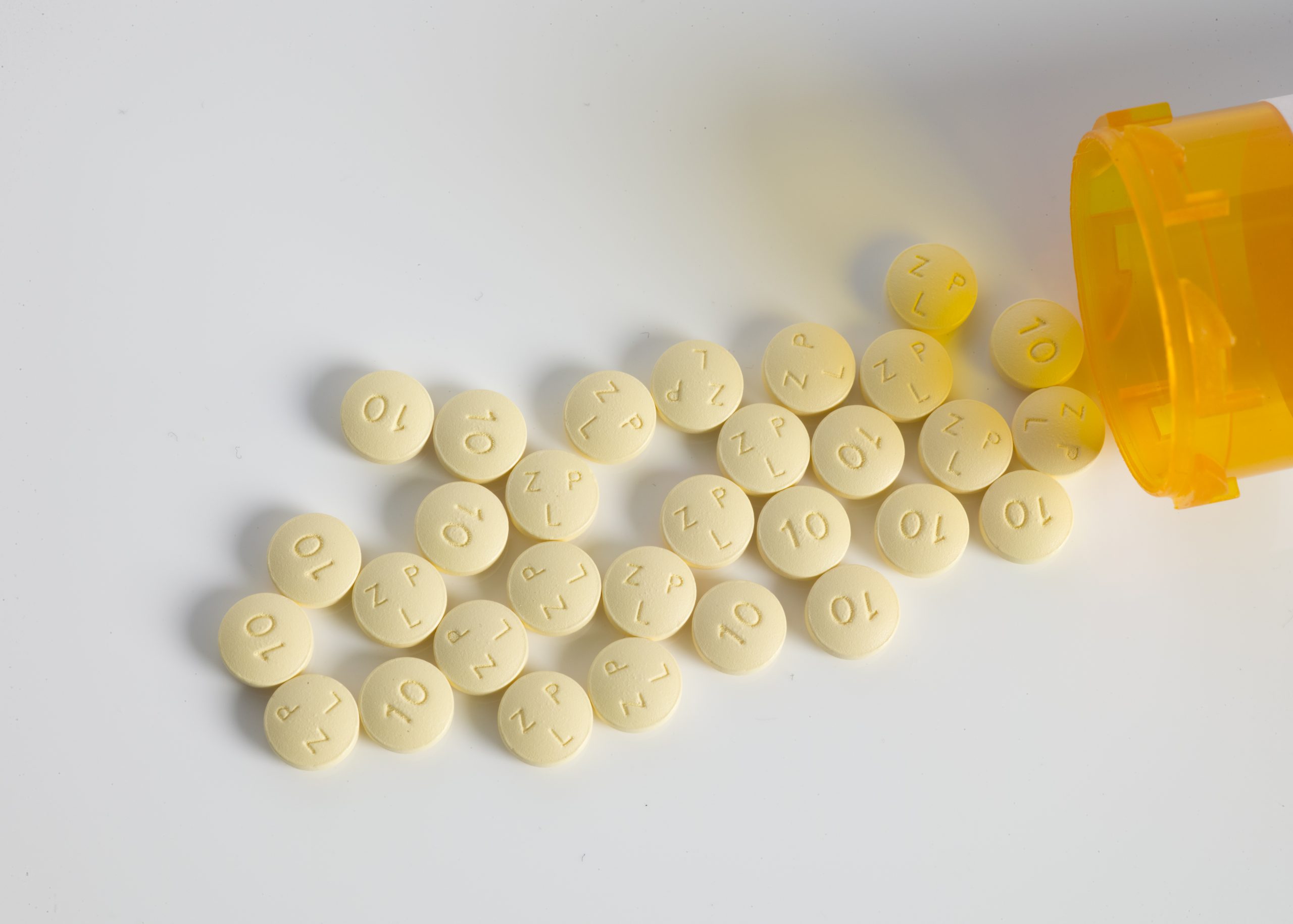

Photo: Image via Flickr (Stock Catalogue)