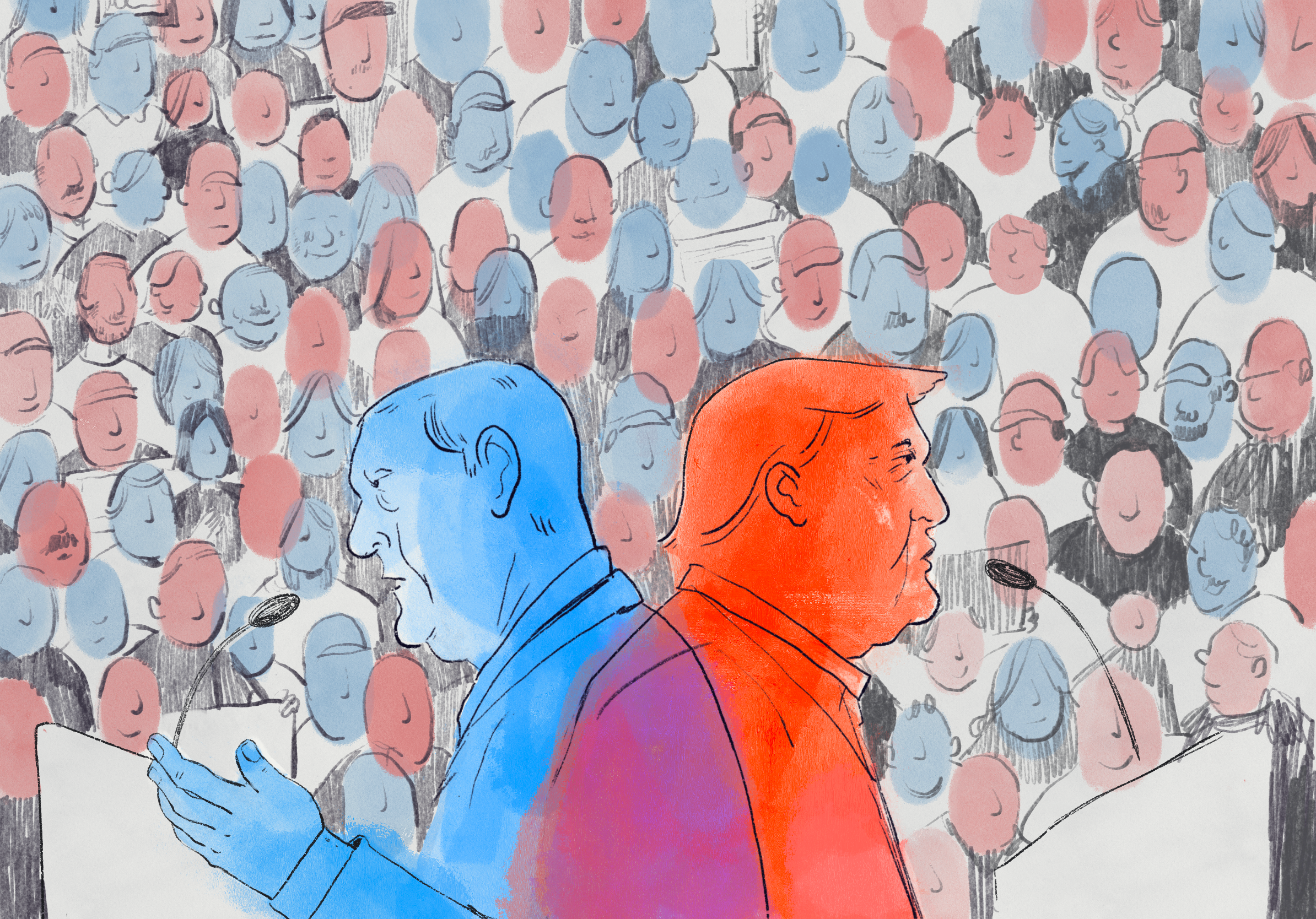

Even after eleven years in office and three indictments for corruption, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin “Bibi” Netanyahu’s political rivals can’t seem to defeat him at the polls. By mid-March, Israel will have had three elections in one year, a tumultuous state of affairs arising from the failures of both Netanyahu’s center-right “Likud” party and rival Benny Gantz’s center-left “Blue and White” party to secure a parliamentary majority following elections in April and September 2019. Netanyahu, like US President Donald Trump, has stunned pundits with his apparent immunity to legal and political consequences. However, his grip on power may be rooted in little more than basic demography.

A recent study by the Adva Center, a progressive Israeli think tank, combined electoral results from the April and September elections with socioeconomic data to measure the class divide between Likud and Blue and White’s constituencies. The study’s socioeconomic component is drawn from Israel’s official geographic socioeconomic ranking system, which ranks each of Israel’s 1,183 municipalities on a scale from poorest to wealthiest. Importantly, the data captures only those municipalities whose residents are eligible to vote in Israeli elections; illegal Israeli settlements in the West Bank are counted, while Palestinian citizens in the West Bank, subject to varying degrees of Israeli civil and military control, are not.

Adva’s analysis may not perfectly capture all the nuances of Israeli voting patterns, but it nevertheless outlines the general picture: The upper echelon of Israeli society votes for Blue and White, the middle class supports Likud, and the lower class, mostly ultra-orthodox Jews and Palestinian citizens of Israel, vote for their respective minority parties, the United Torah Judaism and the Joint List.

At first glance, middle class support for Netanyahu appears misguided. While 11 years of neoliberal Likud economic policy have driven strong overall economic growth, they have plagued the Israeli middle class, which now wrestles with some of the highest levels of income inequality and costs of living among developed nations. However, Netanyahu’s enduring popularity fits logically within the historical and contemporary context of intra-Jewish ethnic politics in Israel. Specifically, Netanyahu’s middle-class support is derived from a tradition of Mizrahi allegiance to Likud and his direct appeals to their tenuous position through anti-elitist and ethno-nationalist rhetoric.

To understand Netanyahu’s success, one first needs to understand the unique history of intra-Jewish ethnic politics in Israel. On the eve of Israel’s founding, its governing elite consisted mostly of Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern and Central Europe who were aligned with the secular-socialist Mapai party. In the ensuing decade, hundreds of thousands of Middle Eastern and North African Jews, collectively known as Mizrahim, immigrated to Israel. Seeking to fortify the border of the nascent state, the ruling Mapai party forcibly transferred Mizrahi families to newly established “development towns” along the state’s geographic periphery. This settlement strategy produced the geographic-economic divide in Adva’s data: Upper-class communities are mostly historically Ashkenazi-dominated towns in Israel’s center, while the middle class constituencies live in the same development towns into which Mizrahim were forcibly resettled in the 1950s.

The electoral power of these middle-class Mizrahi development towns became apparent with the rise of Menachem Begin’s Likud party. Likud’s ideological origins lie in Revisionist Zionism, which emphasizes hardline militarism and free-market capitalism. Begin, an Ashkenazi Holocaust survivor, extended the party’s appeal to marginalized Mizrahi voters in Israel’s development towns by attacking Mapai for its humiliating treatment of Mizrahi immigrants and promoting himself as a defender of traditional Mizrahi religious values that oppose Mapai’s strong tradition of socialist-secularism. Mizrahi support drove Begin to his first electoral victory in 1977, and middle-income Mizrahi towns have consistently voted Likud ever since.

While Netanyahu certainly gains substantial political capital by virtue of being Begin’s ideological heir, history alone cannot explain his continued support amongst Israel’s middle class. A more complete theory would consider the manner in which Netanyahu appeals to the unique socioeconomic position of his Mizrahi development town base. While Mizrahim want to displace the country’s economic elite, this unique social group also realizes its position as a wedge in Israeli society and consequently seeks to avoid falling to the level of the ultra-orthodox and Palestinian citizens of Israel, the country’s most economically and politically marginalized groups. Accordingly, Netanyahu espouses a political program that deftly serves both interests. Following a long tradition of right-wing populism, he attacks the media and justice apparatuses as proxies for the elite while marginalizing Israel’s non-Jewish minorities.

To understand Netanyahu’s political strategy one must also consider how he deals with one of his most serious political threats; Netanyahu has been under state investigation for bribery, fraud, and breach of trust. He was formally indicted in November and will likely face trial in the coming months. Much as Trump has labeled his impeachment a “witch hunt,” Netanyahu has similarly derided his proceedings as an “attempted government coup.” He alleges that the state prosecutor and media are colluding with Blue and White’s Gantz and the center-left bloc to topple his democratically elected government. For Netanyahu’s supporters, the supposed alliance among the prosecutor, media, and Gantz is emblematic of the Ashkenazi elite inhibiting their upward mobility. Accordingly, Netanyahu appeals to middle class support by portraying himself both as a victim of leftist elitism and as a defender of true Israeli democracy.

Just as Netanyahu tacitly promotes middle class advancement by attacking an amorphous “elite,” so too does he seek to prevent the erosion of the middle class by marginalizing non-Jewish minorities. Since Netanyahu’s Mizrahi middle class base lacks the social and economic power of the Ashkenazi elite, they seek to fortify their position against those lower than them in Israeli society—namely, Palestinian citizens of Israel. Similar to Trump’s “America First” rhetoric, Netanyahu promotes this desire for strong Jewish ethnonationalism with a host of racist policies and actions. For example, he accuses Palestinian political parties represented in Parliament of seeking to destroy Israel and warns Israelis that Arabs are voting “in droves.” In July 2019, he organized the passage of the controversial “nation-state law,” which explicitly codified the right to national self-determination in Israel as “unique to the Jewish people” and downgraded Arabic from being an official language to one of “special status.”

Netanyahu’s anti-democratic demagoguery and ultranationalism are certainly troubling. Disdain for him and his policies, however, must not blind observers to the very real structural inequalities that drive middle class voters to support him. A historical affinity for Likud based on past marginalization by the Ashkenazi leftist elite coupled with their current tenuous position within Israeli society give middle class Mizrahi voters logical reasons to support Netanyahu. If nothing else, Israeli politics demands that greater attention be paid to supporters of right-wing populism. Only then will inter-group solidarity truly be possible.

Illustration: Stephanie Wu ’21