Since the landmark Citizens United decision of 2010, U.S. elections have become less about voters and their voices and more about the moneyed elite and their bottomless wallets. Corporations, unions, and wealthy donors funnel millions of dollars into unrestricted Super PACs and outside groups, which take this unlimited cash flow and use it to support or oppose political candidates. The Center for Responsive Politics (CRP) found that 29 percent of campaign contributions in the 2014 congressional election came from the top 0.01 percent of income earners. Furthermore, in 2016, the CRP uncovered that the top 40 individual donors gave more than $1 billion combined to political groups, amounting to about a sixth of the total money raised for congressional and presidential elections for that year.

The rise of big money in politics has well outpaced individual campaign contributions; a survey conducted by CNBC and Survey Monkey in July of 2019 found that only eight percent of eligible Americans had donated to any presidential candidate. Low-income and young Americans were the least likely to donate to campaigns: About 75 percent of Americans with an income below $50,000 and about 80 percent of citizens between the ages of 18 and 24 said they will not donate a penny to the 2020 presidential election. So, we must ask: Is it possible to have a robust, representative, and fair democracy if our elections are mostly funded by the one percent?

In response to the rising power of unrestricted Super PACs and outside groups, Harvard Law School professor Larry Lessig wrote an Op-Ed for the New York Times arguing for the implementation of national “democracy vouchers.” Under this plan, a small portion of federal taxes–say, $50 a person–would go into a rebate in the form of a voucher. Before every election, whether on a local or national stage, every voting citizen of the United States would receive a voucher in the mail that they could contribute to a political candidate of their choosing. If voters don’t choose to use their vouchers, the money would be donated to their registered political party. The linchpin of the voucher system is that all political candidates who participate have to vow to only accept donations of under $100 and to refuse Super PAC money.

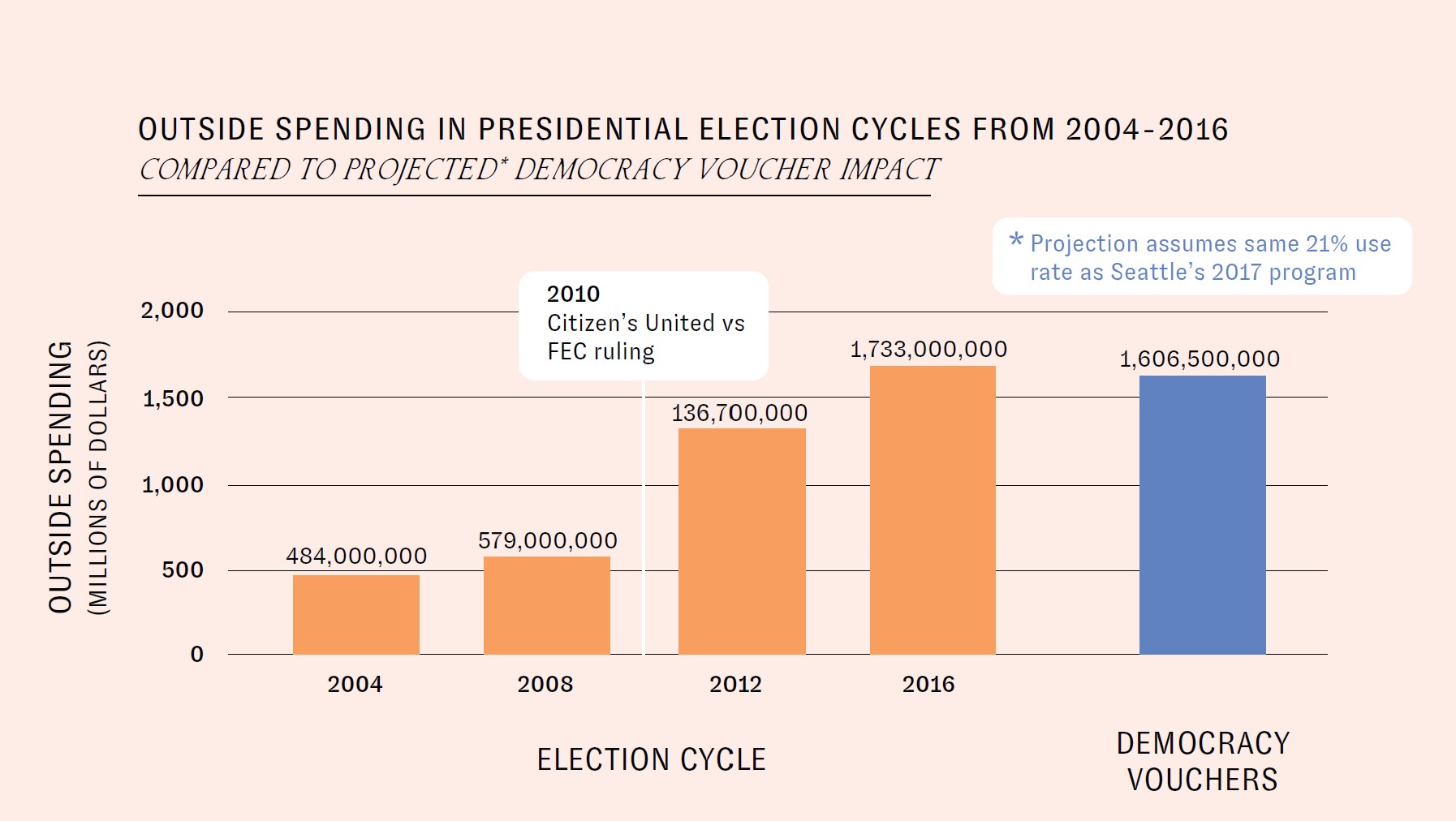

Proponents of democracy vouchers do not claim that the program would remove big money from politics but that they would instead champion the value of small donations. More money, according to their argument, beats big money. Indeed, giving every eligible American voter $50 would channel over $12 billion in additional funding into our elections. In this case, the billions of dollars coming from the 0.01 percent would be matched by billions coming from the 99.9 percent. If only half of Americans use their hypothetical $50 voucher in the 2020 election, about the same amount of money would be raised through vouchers alone as in the entire 2016 election. Not only would democracy vouchers radically change American campaign finance, but they also have the power to revolutionize political engagement. The ability to donate to a political campaign puts power back into the hands of the average American voter.

Although vouchers have not yet been instituted on a broad scale, the system has proven to be quite effective in local elections. In January of 2017, the city of Seattle implemented the country’s first democracy vouchers program for its own local elections; $43 million from a ten-year-property-tax were turned into $100 vouchers and sent in the mail to every Seattle voter. Although the project came with high administrative costs of over one million taxpayer dollars and had lower participation than expected, it was still overwhelmingly successful: Candidate Teresa Mosqueda raised over $300,000 from democracy vouchers and ultimately won a seat in the Seattle City Council. In addition, 84 percent of people who sent back their vouchers said they had never donated to an election before, and small donations tripled from 8,200 in 2015 to about 25,000 in 2017, when the project was launched.

The vouchers were especially effective at inspiring political engagement from groups with historically low donation rates to political campaigns: the Seattle Times found that the program boosted participation from younger and low-income voters. Compare, for example, the Seattle mayoral race, which did not accept democracy vouchers, and the city council race: While only 478 people with an income of under $50,000 donated to the mayoral race, 1,292 people donated to the city council race. Furthermore, the Seattle experiment found a marked increase in citizen participation in elections at large. Many felt new agency as a result of their ability to contribute to a process otherwise governed by elites. One woman who used her voucher in the 2017 election said, “People like me can contribute in ways that we never have before. We can participate in ways that big money always has.”

The success of democracy vouchers at the local level in Seattle has spurred some political pundits to call for the implementation of the experiment on a broader scale. In fact, during his 2020 presidential campaign, former candidate Andrew Yang proposed a “democracy dollars” program, an idea which resembles democracy vouchers on a national level. According to Yang, his voucher would work to overpower the influence of big money: “The government has been overrun by corporate interests, [and] my answer is to wash the money out with people-powered money. [Democracy dollars] would wash out the lobbyists’ money by a factor of eight to one. That is the only way we will win.”

Democracy vouchers have the power to revolutionize the way American voters think about and interact with local and national elections: They spur greater political engagement among disillusioned and often forgotten Americans and undermine the influence that the top 0.01 percent have on our elections. Moreover, the vouchers are part of a large-scale push to recognize the power of grassroots organizing and small donations. A look at 2020 candidates like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, who have condemned the influence of donations from Super PACs, demonstrates the growing power of small donors: Sanders’ campaign has over five million donors and an average donation of just $18, boasting the most donations in one fiscal quarter of any candidate in history. If these candidates want to boost the viability of such campaign finance strategies, democracy vouchers are a natural next step.

Having already shown success on a local level, a national rollout of democracy vouchers would spur even more political engagement, especially among groups with traditionally low voter turnout. Democracy vouchers’ presence in the platforms of multiple presidential campaigns demonstrates their widespread acceptance and feasibility. Not only would democracy vouchers support the emergence of future grassroots campaigns, but they would also diminish the relative power of Super PACs and put power back in the hands of voters.

Infographic: Madi Ko ’21 and William Jurayi ’21