In the pandemic-era scramble of digital education delivery, the line between public and private has been unduly blurred. Remote learning has brought one particular learning tool — remote invigilance, or more colloquially “online proctoring” — to the fore. And students are not happy. Considering the unprecedented threats online proctoring services pose to student privacy, accessibility, and health, educational institutions should categorically reject these kinds of online proctoring services and seek other pedagogical approaches to evaluate student learning.

Online proctoring services for higher education are exploding in popularity, with an estimated 19 billion dollar global market size. One market leader, Proctorio, boasts a customer base of over 1,000 universities and estimates it will administer as many as 30 million exams by the end of the year. These companies have experienced accelerated growth given the pandemic and are expected to remain in high-demand as online education becomes more prevalent. While these proctoring systems vary in functionality, the general idea is this: to disincentivize cheating on virtual exams, students are either remotely monitored by a human proctor or are recorded (visually and audibly) for the duration of their exams. In the latter case, AI technology will detect and flag any movements that raise suspicions of cheating. Yet a barking dog, a glance down to solve a math problem, or a passerby sibling in the background — any extraneous sound or object — can subject students to scrutinized review and even disciplinary action.

Perhaps the most salient danger of online proctoring concerns student privacy. While instructors and college administrators justify the use of such technology as deterrence against academic dishonesty, online proctoring services collect far more data on students than an in-person exam environment. At a minimum, students are forced to consent to third-party services accessing their cameras, microphones, screens, and browsing activity. Platforms that make use of AI technology collect biometrics related to facial identification, eye tracking, and even keystrokes. Many services also require students to give a 360-degree view of their testing environments prior to the exam. One company, Examity, started recruiting contractors in India to work as proctors remotely instead of in a supervised office. This grants alarming access to strangers to view streams of the most intimate spaces of students’ lives.

Moreover, while online proctoring services claim to destroy exam records after a short period, they are far from impenetrable. In July 2020, over 444,000 user records from ProctorU databases were compromised and published by hackers. Reportedly, the company has since upgraded its security. Since the shift to remote learning was largely unpredictable, administrators have noted concerns about not having enough time to thoroughly understand the implications of the technology before rushing its implementation. In a conversation with The Washington Post, one university administrator justified the use of ProctorU and a similar service, Honorlock, with the sentiment that “desperate times call for desperate measures.” This perspective ignores the fact that the pandemic has irrevocably changed the educational landscape, and a return to in-person learning is unlikely to mark the end of the expanding role of technology in education. A Harvard Business Review study describes 2020 as an inflection point, which has created the perennial opportunity for “technology-driven disruption” that may have set a new status-quo in classrooms. An April survey found that over three-quarters of universities may use remote surveillance proctoring during the pandemic. While a frantic turn to online proctoring may have been justified in the immediate aftermath of the mass exodus of students from college campuses, student privacy cannot continue to be compromised.

Online proctoring services exacerbate gaps in accessibility and penalize disadvantaged students. These technologies, largely designed for neurotypical students, are likely to flag tics or darting eye movement as “abnormalities,” in the language of Proctorio. Students with neurodevelopmental disabilities or behavioral disorders like ADHD are forced to seek out accommodations; thus, they not only must disclose their health circumstances to third-party administrators but face yet another barrier to educational achievement as compared to their neurotypical counterparts. Ironically, the use of AI technology is inconsistent with peer-reviewed neuroscience research that eye movement is correlated with neural reactivation. To mandate students with Tourette’s syndrome, then, to be recorded in an already stressful testing environment is not grossly unethical, but likely ineffective.

Additionally, Black and brown students have reported difficulties in having their identities verified by proctoring service ExamSoft due to the color of their skin. For instance, they might be asked to sit in a better lit environment despite having lamps besides them. Trying to resolve these facial recognition failures cuts into students’ exam time and, at the very least, adds undue and disparate burden to students of color. Online proctoring also worsens the digital divide for students of lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Education non-profit The Education Trust-West estimates that more than 245,000 students in the state of California alone lack access to reliable internet. Students who rely on public computers, such as those in libraries, may not be able to download the additional software to take exams. Some schools have taken notice: in April, UC Berkeley announced it would prohibit the use of online exam proctoring for the rest of the semester, citing in part concerns about access to compatible devices and internet connection for low-income and rural students to use proctoring technology.

Laden in the marketing of virtual proctoring services is an appeal to fairness, integrity, and transparency. Proctorio, for example, describes itself as “the world’s most advanced integrity platform.” For school administrators, educators, and even honest students who do not want to reward cheating, this is a narrative they can easily buy into. But rather than encouraging students to take ownership of their learning, the use of online exam monitoring breeds a culture of student distrust. Digital Pedagogy Lab co-founder Jesse Stommel argues that “cheating is a pedagogical issue, not a technological one.” At Brown, the Digital Learning and Design Center has explicitly criticized the use of online proctoring systems, articulating, “online proctoring systems can only make cheating more difficult not eliminate it” and adding “online proctoring may significantly degrade the student learning experience.”

Pedagogically, the use of virtual proctoring systems reveals the emphasis that educational institutions place on recollection over mastery. Requiring students to lock down their browsers during exams, for instance, implies that the answers are readily available online. While born of unfortunate circumstances, the shift to remote learning should prompt educators and administrators to reconsider educational approaches in student evaluation. Bloom’s Taxonomy, a foundational education framework, places “remember” and “understand” at the bottom of the pyramid and “analyze,” “evaluate,” and “create” at the top, and cognitive psychologists have generally rejected rote memorization alone as an effective strategy for comprehension. Accordingly, instructors should seek to deliver assessments that task students with extending their learning to analyze novel situations.

As number two pencils are traded for keyboards and bedrooms are converted to classrooms, educational institutions must acknowledge the overwhelming harm posed to students by online proctoring services and terminate their use. The cybersecurity and privacy risks are too unknown and the accessibility disparities too high to justify their continued use in higher education. Importantly, educators must also take the opportunity to rethink pedagogical approaches and resist the temptation to see technological solutions as panaceas for enduring challenges to learning.

Outsourcing academic integrity to third-party corporations is a shoddy solution that flies in the face of the honor code that grounds the student-educator relationship.

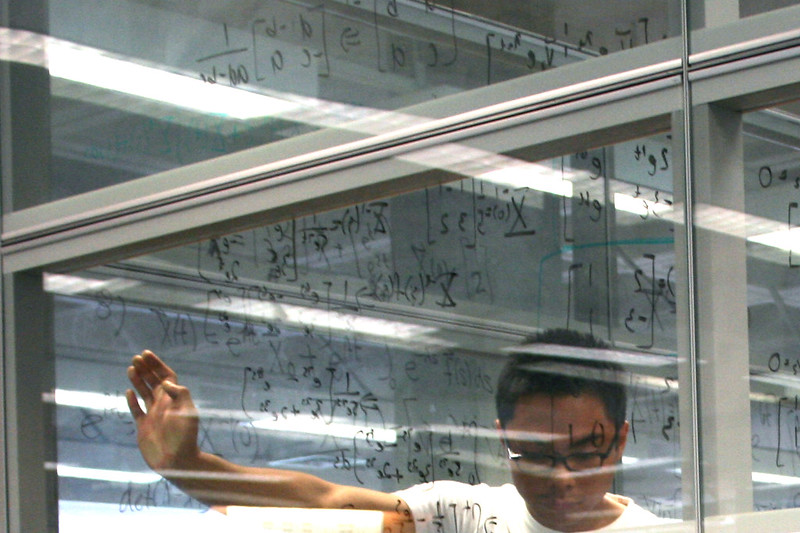

Image: Photo via Flickr (emdot)