If you’ve ever had a Crunch Bar, there’s a chance a child slave in Côte d’Ivoire produced the cocoa. As illegal as that sounds, the question of whether US law can punish the two companies—Nestlé and Cargill—accused of aiding and abetting such slavery remains unresolved. But within the next few months, the Supreme Court will settle that question in Nestlé & Cargill v. Doe. The Court will decide if, moving forward, multinational corporations will enjoy impunity or face accountability when they violate human rights abroad.

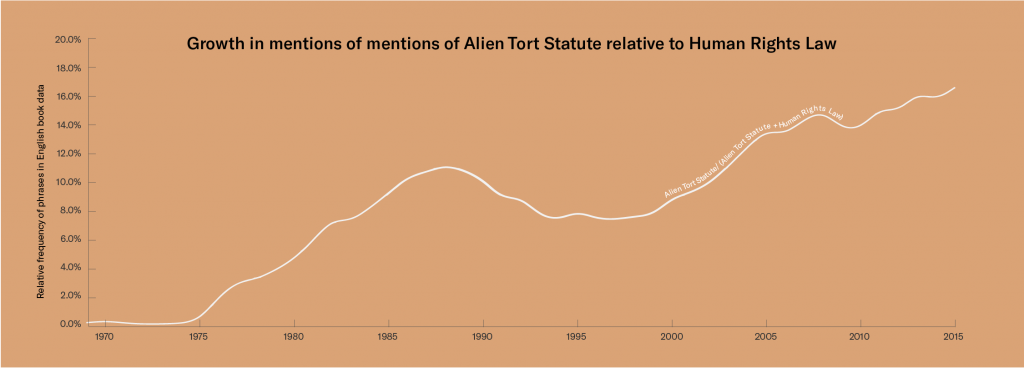

How could US courts have jurisdiction over this case, given that the abuses occurred in Côte d’Ivoire and the plaintiffs are foreigners? The answer is the Alien Tort Statute (ATS), an arcane provision of the 1789 Judiciary Act. It grants federal courts jurisdiction over “any civil action by an alien for a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.” Simply put, it allows foreigners to seek relief in US courts for violations of international law. Originally conceived to safeguard the early republic’s foreign relations, the ATS has become an avant-garde tool for international human rights accountability. But there exists a tension between the ATS’s original objective and its current human rights orientation. While the statute is a promising tool for American corporate accountability, applying it to human rights violations globally would insult the sovereignty basis of international law and damage US foreign relations.

A literal reading suggests that the ATS affords “world court” authority over international law violations, but its original formulation had more modest objectives. The 1784 Marbois-Longchamps affair in Philadelphia serves as a useful origin story of the statute. Charles Julian de Longchamps was a French adventurist with a shady, bellicose reputation who immigrated to Philadelphia. Amid a disagreement with Barbé de Marbois, a well-respected French diplomat, de Longchamps struck de Marbois with a cane. Assault of a diplomat is an unambiguous violation of the law of nations—or what we now call international law—so an inability to punish de Longchamps would communicate to the rest of the world that the early United States was not a serious player on the global stage. This issue nagged at the Constitution’s framers. Years later, Alexander Hamilton argued in Federalist No. 80 that failing to give redress to foreigners victimized by Americans would be “among the just causes of war,” and so federal courts should preside over international law claims. He proposed something resembling the ATS, and his rationale suggests that the statute’s intent was to prevent feuds from escalating into wars.

At first glance, the basic fact pattern of the 10 Nestlé & Cargill case seems to fit well with the ATS’s original vision of accountability for Americans on foreign soil. The plaintiffs, who are foreigners, are suing two American companies for committing torts, defined as inflictions of harm that merit civil damages, against them. But applying the ATS to non-American human rights violators, while tempting, is inconsistent with the law’s original vision. The first case that conferred liability under the ATS on a foreigner was Filártiga v. Peña-Irala in 1980. In Filártiga, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals found that the former Paraguayan Inspector General, who had immigrated to the United States, could be held liable for torture he committed under dictator Alfredo Stroessner. The court argued that international human rights laws against torture fall under the “law of nations” and are thus subject to ATS jurisdiction. It is hard not to celebrate the Filártiga case for holding a torturer accountable. However, the reasoning does not comport with the ATS’s original objective of protecting US foreign relations, since no one involved was a US national when the torts were committed.

In fact, broad application of the ATS to foreign perpetrators could strain US relationships with other countries, since the international law system prizes sovereignty. For a human rights claim to proceed in international courts, the country of the defendant must first accept a court’s jurisdiction in writing, either ad hoc or by treaty. But subjecting a foreigner to the jurisdiction of American courts without the consent of their country of origin affronts basic principles of international law. Acknowledging this conflict, recent Supreme Court decisions have limited the ATS’s scope, but their vague language has given lower court judges considerable latitude to interpret these decisions as they wish. A recent split in circuit court interpretation led to Jesner v. Arab Bank, a Supreme Court case that decided whether Arab Bank, a Jordan-based financial institution, could be held liable for aiding and abetting terrorism abroad. In response, the Jordanian government led an amicus brief arguing that the case was a “direct affront to its sovereignty.” Citing potential damage to foreign relations, the Supreme Court ruled that the ATS cannot apply to foreign corporations.

Whether or not you believe Jordan’s argument, its brief foreshadows a world in which wide application of the ATS to foreign defendants draws contempt from the international community for American violations of sovereignty. Many countries already scorn the United States for its interventionist approach to foreign policy, so using the statute to give “world court” authority could draw further scrutiny. It could also invite accusations of hypocrisy, given the United States’s refusal to join the International Criminal Court and its cavalier attitude toward human rights in its wars in the Middle East.

But a ruling in favor of Nestlé and Cargill could still have adverse effects by communicating to the world that American multinational corporations can abuse human rights with impunity. Therein lies the dilemma of the ATS: Applied to torts committed by Americans or American companies, it can both protect human rights and maintain amicable foreign relations. But applied to torts committed by foreigners, it can only achieve one of those two outcomes.

Anyone who values human rights and the rule of law should have reason to celebrate if the Supreme Court chooses the path of corporate accountability in Nestlé & Cargill. But this ruling should not transform the ATS into an all-encompassing tool for human rights enforcement against foreigners. Expanding the ATS’s scope to compensate for the failures of international human rights courts may seem tempting, but given the importance of sovereignty in international law, wide ATS applicability will only be a scourge to US foreign relations. In the long run, it may even impede progress on human rights, as the United States could find itself with less leverage to persuade countries with poor human rights records to strengthen their enforcement mechanisms. The most sustainable path toward global human rights accountability, then, is the establishment of robust, consent-based international courts. This approach will not provide the immediate rewards that the ATS offers, but it will be more lasting, effective, and responsible.